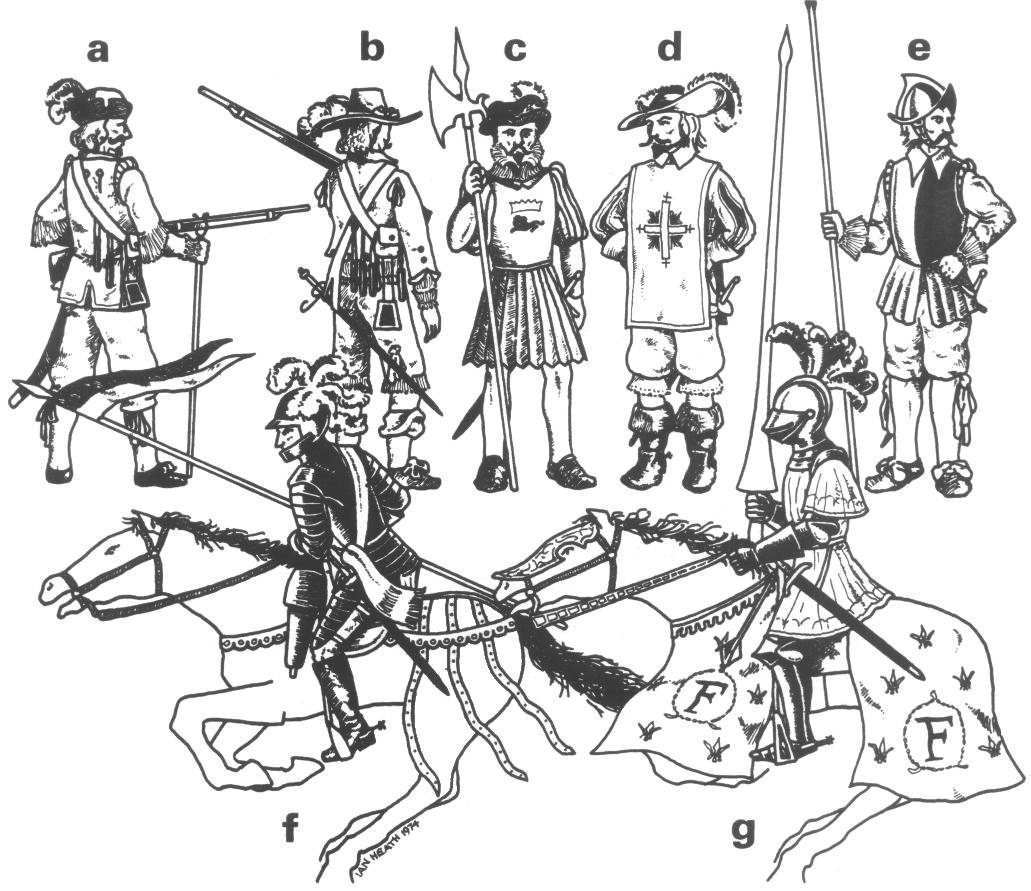

French flags. a the standard pattern. White cross of France. Background variable, in Italian Wars often red, but could also be striped as in b and c, or carried in alternative shapes as d and e. The older regiments carried 'a' with the following backgrounds: Gardes Francaises - blue; Picardy - scarlet; Navarre - russet; Champagne - green; Piedmont - black. f Royal Standard. Gold fleur-de-lys on blue background until Henry IV's reign, then and afterwards white. g cavalry flag 1643. Many had devices and slogans like this, but could also be a small square version of 'a', h and i banners of Francis I's gendarmes (probably Royal Guard). Red or red and yellow with gold salamander ('h'); St Michael and dragon ('i'). Suns often appear on similar flags.

j Catholic flag of the Wars of Religion. Background green with black and gold St Michael, wings and cross on shield white, dragon gold, red blood, anchor silver.

k infantry (left) and cavalry flags, also from the Wars of Religion.

|

|