Lombard soldier in an 11th Century Exultet Roll

|

|

From "Dedication to Duke and Emperor," Exultet Roll, 11th century AD, south Italian, Museo Civico, Pisa

Source: Il Palazzo di Sichelgaita

Referenced as figure 425 in The military technology of classical Islam by D Nicolle

568. Manuscript, "Dedication to Duke and Emperor," Exultet Roll, 11th century AD, south Italian. Museo Civico, Pisa (Ave).

Referenced as figure 675B in Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050-1350, Western Europe and the Crusader States by David Nicolle

675A-C Exultet Roll, southern Italy, 11th century

(Museo Civico, Pisa, Italy)

A picture dedicated to Duke and Emperor. This suggests that it was made in an area within, or closely associated with, the Empire yet also within the south Italian cultural zone where such Exultet Rolls were used. Part of the Duchy of Spoleto or the rump of the Duchy of Benevento, which fell under Papal control in the 11th century, fit such a scenario. The style of the crudely drawn figures is unlike most other sources and seems to reflect, however distantly, Byzantine art. The main figure (B) has a small round shield and a spear with wings below the blade. An identical spear is seen elsewhere (C). He seems to wear a hood or coif, perhaps the former judging from the floppy headgear of the second figure (B). The cloth or cloak across the first figure’s chest (A) is also seen elsewhere in the Mezzogiorno. Both figures also wear some form of sleeveless armour on the upper parts of their bodies. This is rendered in such a stylised form that its construction can only be guessed at, though its lack of sleeves) and its length, reaching only to the waist, does suggest a small lamellar cuirass.

An extract from A Prôtospatharios, Magistros, and Strategos Autokrator of 11th cent. the equipment of Georgios Maniakes and his army according to the Skylitzes Matritensis miniatures and other artistic sources of the middle Byzantine period.

Γ) Lombard infantryman or Pelthastis of Thema of Laghouvardhìa :

We read in the sources that, together with mercenaries and East-Roman regular troops, the army of Maniakes was composed also of Lombards, sent by Prince Guaimarius IV of Salerno279. Looking for an artistic source for the reconstruction of such kind of warriors (plate 1C) we could put our attention upon a figure taken by the miniature “The temporal Authorities”, of Exultet 2, today preserved in Pisa Cathedral, but produced in Southern Italy, probably at Capua, in 1059 (fig. 14)280.

This Exultet Roll, about 95 cm. long, is formed by 12 parchment sections, in latin written in Beneventan Lombard style. The figurative cycle presents 28 scenes, 11 of which formed a Christ cycle, from the Annunciation to the Last Supper. It follows the glory of Christ, 4 scenes for the preliminary introduction, 9 scenes for the Laus Cerei and 3 scenes for the liturgical commemorations, i.e. “spiritual” and “temporal” Authorities.

The analysis of this parchment suggests that the roll had been produced in the area of the Longobardia minor, in a chronological continuity at the end of the 10th and the beginning of the 11th century. The work comes from a very rich centre, and was probably destined for a Bishop. For his iconographic links with the famous manuscript 132 of the Montecassino Abbey, the Rabano Mauro, with the M. 397 of the Pierpont Morgan Library of New York and with the Salernitan ivories of the Cathedral, as well as with the frescoes of S. Michele at Olevano on Tusciano and Sant’Angelo in Formis, some authors proposed a Beneventan or Amalfitan production. But a recent hypothesis identifying the Bishop represented on the Exultet as Ildebrandus, Archbishop of Capua from 1059 to 1071, underlines the possibility of its Capuan origin281.

Capua in 1059, just before the Norman conquest, was still a Lombard city under of the control of the family of Pandolfus IV, who died in 1049, that famous Pandolfus “the wolf” who, allied himself with Constantinople against the Pope and the German Emperor, was the uncle of the Salernitan Prince Guaimarius IV and the protagonist of the Southern Italy’s policy of the first half of 11th century282. His troops, as well as those of his relatives, were under the strong influence of Constantinople, so it is possible that the representation of the warrior, in the miniature, is a true portrait of an original guardsman. In any case Southern Italy was exposed to the many influences coming

279 See note 14 above.

280 See Ministero dei beni culturali, Exultet, pp. 156-157 and p. 171; fig. 14 is taken from it.

281 See Ministero dei beni culturali, Exultet, pp. 156-157 and p. 170.

282 See Rasile M., Normanni, Svevi, Angioini e Durazzeschi, Itri 1988, pp. 7-14; Fedele P., Scritti storici sul ducato di Gaeta, Gaeta 1988 pp. 78-100.

45

from Muslim, East-Roman and Mediterranean world, influences reflected also in the military garb of its small Principates283.

The fact that in the miniature he does not wear a sword could be indicative of his court function as a simple guard. The man in the miniature could portray a Lombard medium infantryman (may be a πελταςστηs)284 enlisted in the regular troops of the Thema of Laghouvardhìa, as well representing one of these Lombard Guards, armed with a mixture of East-West equipment, who garrisoned the camp or the commander’s tent.

His “Lombard” origin could be derived from the appearance he shows in the Exultet, where he is represented with high stature, large eyes and red beard. We know that high stature was a characteristic of the Lombard warriors, and this is illustrated in the episode remembered by Guglielmo Appulo285 at the battle of Cividale (1054) when the Lombard and Suebian warriors of the Pope Leo IX mocked the Normans of the Robert the Guiscard for their shortness286. On his head he wears a whole metallic single-piece conical helm (καςσςσιδιον)287. This kind of helmet is often associated, in biblical illuminations of Byzantine art, with representations of enemies of the Israelites288, so that its attribution to the enemies of God could be interpreted as linking with the Agarenoi, enemies of the new Chosen People, the Orthodox Christians of the Roman Empire. But it is not a rule: in Scylitzes Matritensis289 as well in other artistic works290 this kind of helmet is worn by Roman soldiers, so that its use by Mediterranean races could eventually be related to its typology291. The use of this specimen in 11th cent. South Italy could eventually confirm the strong influence of both Muslims and East-Romans on the military context of these regions.

The blue colour of the under helmet hood in the miniature reveals the presence of a mail coif, worn over a natural ochre hood, maybe of padded material, which covers, with its edge, part of the armour. The use of metallic coif or

283 See Nicolle, The Normans, pp. 28-46 and pl. G; Idem, Arms and armours of the Crusading Era, I, pp. 247 ff., figg. 661 ff.

284 Sylloge Tacticorum, 38,7 ; I would like note the klibanion and the helmet open on the front, as described for the Πελταςσται.

285 Guglielmo Appulo, II ; Muratori L., Annales d’Italia, Dalprimoannodell’eravolgareal MDCCLXXXI, XXV, p.242.

286 The episode had a tragic epilogue for the Lombards, who were cut to pieces by the Normans. Excavations on the battlefield revealed bodies of very high stature men with signs of terrible wounds. S. Rasile, Normanni, pp. 16-17.

287 On Καςσςσιδιον see note 209 above.

288 Cfr. for example folio 469v of 11th cent. Smyrne Pentateuch, in Nicolle, Arms and armours, p. 30 fig.17a; Huber, Bild und Botschaft, folios 402r, 421v of the Vatopedi Octateuch, figg. 125, 134.

289 S. folios 99v, 149r, 150r, in Cirac Estopanân, Reproducciones ..., fig. pp. 301, 354-355.

290 S. Kolias, Waffen, pls. XX (Cod. Ath. Vatop. 760 folios 265v and 286r).

291 The mediterranean origin of this piece of equipment is also attested in a very fine tall one-piece conical specimen of 10th cent. date, preserved in the Instituto de la Historia de Valencia, s. fig. 15 in Egfroth (Lowe S.), More and yet more helmets, in Varangian Voice 33, November 1994

46

σκαπλιον292 of mail by Roman soldiers is well attested from the third century onwards in artistic sources293. But the coif shown in the Exultet of Pisa has got something more. It could represent an application of the evolution of the famous East-Roman zába, which in this age designs not only the mail cuirass but also parts of equipment for arms, legs and head composed by felt, cotton and coarse silk with metallic protections of lamellar, scale and, as in this case, mail armour, directly stitched upon a felt support294 (plate 1C). Around his neck the man seems wear a remainder of the Roman military heritage of Italy and Byzantium, a red maphòrion295 or scarf.

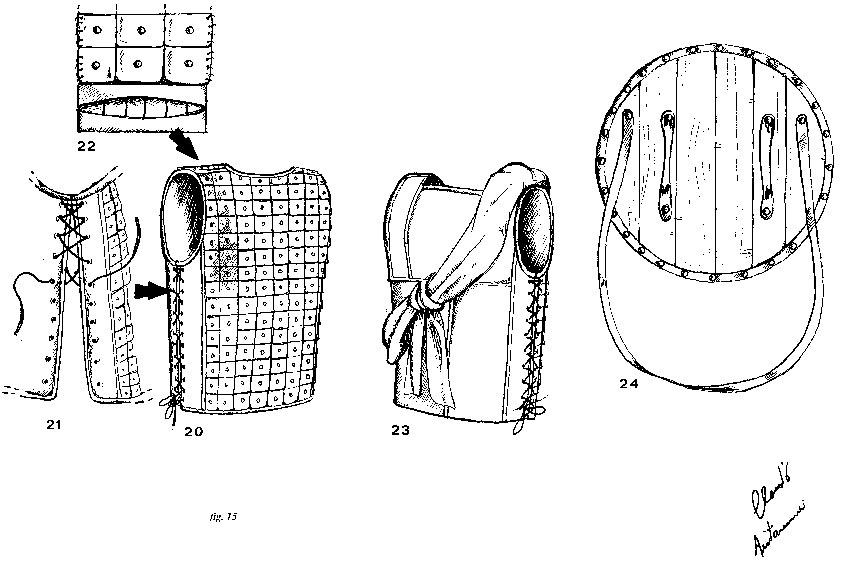

The main defensive armour is a klibanion (fig. 15 n. 20 and plate 1C) composed by 16 rows of rectangular flanked scales of golden metal296, attached one by one to a leather fabric by means of a central rivet. This kind of attachment has been reconstructed from identical specimens found in a Russian context, following the suggestion of the Russian archaeologist Kirpicnikov that such kind of metal plates were fastened to a leather or linen fabric297. This kind of κλιβανια could be of the type having πεταλα (lamellae) only at the front, and plain leather or linen at the back (fig. 15 n.23), mentioned by sources298. They were probably composed by two leather valves

292 Kolias, Waffen, pp. 43-44; s. also Du Cange, Glossarium, col. 1382; and for the 6-7th century army the Strategikon, I, 2; VII, 15; X, 1; the coif could have been worn alone or under the helmet, or even over the cap s. Aussaresses F., L’armée Byzantine à la fin du VIe siècle d’après le Strategikon de l’Empereur Maurice, Paris 1909, p.48.

293 S. for example folio 471v of 11th cent. Smyrne Pentateuch, in Nicolle, Arms and armours, p. 30 fig. 17r ; the 11th century sleeping soldiers at Holy Sepulchre in the Church of Karanlik, Goreme, in Jerphanion, Les Eglises, pl. 103/1; Cod. Ath. Esphigmenou 14, folio 136v, in Treasures, II, fig. 333, and s. also folio 343r fig. 340 ; s. Kolias, Waffen, note 58 for other examples.

294 Kolias, Waffen, pp. 65-67; Idem, Zaba, 28ff.; the kind of mail armour in the reconstruction has been copied by the finds of Danube,Veliki Gradac, s. Jankovic, Implements, p. 59, pl. V fig. 64/17; to make clear as it was worn the fresco of Resurrection at Goreme in Kappadokia quoted in the previous note, even if the coif there is scale covered. The fragments of ring armour found in Veliki Gradac are from mail composed by ringlets 0,9 cm. in diameter, linked together by tiny rivets, of circular crossed section. On the opposing side of the rivet, on the larger part they are elliptic and in the place of their riveting they are flattened. Mr. Antonucci suggests me that the kind of coif worn by the Exultet Pisa warrior could have been of jazeran, jazerant or kazaghand type, i.e. with flat rings sewn on the felt or leather support. For the term cfr. Tarassuk-Blair, Arms & Weapons, Verona 1979-1986 under v.

295 To protect the neck from the armour’s chaffing. It was the scarf of the Roman classical miles, called focale. See G. Sumner, Roman Army, wars of the Empire, London 1997, pp. 89-90 ; Pio Franchi de Cavalieri, Come andavano vestitied armati i Milites, p. 207 n. 5. The Italian middle age and especially the Dark Ages is very interesting because of the particularity of the military equipment, showing a mixture of “classical” medieval equipment together with vestiges of the old Roman tradition, and these latter not only derived from the always present Byzantine influence. But this is matter for other article.

296 The count of the rows is from the Exultet figure.

297 S. Kirpicnikov A.I., “Russische Körper-Schutzwaffen des 9-16 Jahrhunderts”, in Waffen und Kostümkundeder Gesellshaft für historische Waffen und Kostümkunde, 1, 1976, p. 25-28 fig. 9.

298 Achmet, Oneirokritikon, 114 ; Leo, Naumachica, I, 14 ; Nikephoros Ouranos, Naumachica, VI, 12 ; s. also Kolias, Waffen, p. 46 ; Haldon, Imperial Military Expeditions, pp. 278-279 ; it is interesting to mention that in the Menologion of Basil II an armoured warrior, even if bare-headed, is armed in an almost identical way ; the κλιβανιον is identical, as well the maphòrion around the neck. Only, the klibanion is worn over a zoupa, showing the cymation and the shoulder protection pieces. The shield of this warrior seems be a leather shield, painted green, of the type (δορκα) used by the fighting sailors called Phampili (De Cer, II, 579). If my identification is correct, the use of such a κλιβανιον could be linked with the type “with lamellae only on the front” described for fighting sailors. A very good colour photo in Upjohn-Mahler-Wingert, Storia Mondiale dell’arte, Dagli Etruschi alla fine del Medioevo, Oxford 1949-1958, p. 99. Identical armour but of metallic plates is worn by a warrior in the same Exultet of Pisa, Temporal Authorities, 2, s. Exultet, p. 173.

47

fastened on sides by means of leather thongs (fig. 15 n. 21) as those you could see in the miniature of David and Goliath of Cod. Parisinus Graecus 139 of 10th cent299. This is a extraordinary source which shows us a way of fastening a leather cuirass, and the same way of fastening is shown for the scale klibanion worn by Basil I in the folio 86r of the Scylitzes.300

Smaller lamellae grew thinner narrowing on the shoulders. So in the reconstructed cuirass of our man the 16 rows of scales end on the shoulders with what look like a transversal joint301 which could reinforce the idea of two valves united and fastened, on the sides by laces, and on the shoulder, by means of clasps (fig. 15 n. 22) which may be similar to some fragments of the lamellar armour found in the Great Palace302.

The under cuirass garment does not look as muscled-shaped in the source, because the warrior, apart from helmet and armour, is armed in a more western fashion. It has got, in any case, decorative shoulder pieces remembering the ancient ones (fig. 15 n. 23). The spear carried by the men in the Capua Exultet is undoubtedly of the typical “winged” one, so called for its iron projections on every side of the groove in the wood pole. This weapon, derived from Germanic races, was used or for war or for hunt, but as a war weapon it reached its finest development in the Carolingian age, as attested and used by all the Northern and Mediterranean races, including East-Romans, Franks, Vikings, Muslims and Slavs303.

The specimen in the reconstruction has been copied from point GW959 found in the Arabo-Byzantine shipwreck of Serçe Limani304. Apart from its similarity, in style and proportions to

299 Heath, Byzantine armies, p. 33.

300 The detail is very clear in Sherrard, Byzanz, p. 67, where the ending part of the laces goes out from the right side of the κλιβανιον.

301 Better visible at the scanner.

302 Talbot Rice, The Great Palace, pl. 58 fig. 7.

303 S. Kovacs L., Bemerkungen zur Bewertung der Frankischen Flugellanzenim Karpatenbecken, in Mitteilungen des Archäologischen Instituts der Ungarischen Akademieder Wissenschaften, 8/9 1978/1979, pp.97-119, pls. 59-68; Paulsen P., Flügellanzenzum archäeologischen Horizont der Wiener Sancta Lancea, in Frümittelalterliche Studien 3, pp. 289-312, pls. XIX-XXI; a good specimen in a Lombard-East-Roman context was found in Nocera Umbra, grave 6, together with other weapons of Eastern Mediterranean origin; s. Paroli-Arena, Museo dell’altoMedioevo, Roma 1993,pp. 32-33 fig. 29; the evidence of the use by East-Roman troops of this kind of weapon is well attested, for Italy, in the famous Crucifixion fresco of Santa Maria Antiqua, in situ, Forum Romanum, dated 700 circa, where Longinus holds this kind of spear, cfr. P. Romanelli, Santa Maria Antiqua, Roma 1999 pl. VII; a very nice specimen found in Rome and dated to the same period is now shown in the Crypta Balbi Museum. For 9th cent. Constantinople, we can clearly distinguish it in the hands of one of the Guards of Solomon in folio 215v of Gregorius Nazianzenus 510, representing probably an Imperial Primikerios Kandidatos, s. note 94 above. For their use by the Vikings see Nurmann, The Vikings, pp.14-15; and the Muslims Nicolle D., Armies of the Caliphates 862-1098, London 1998, p. 15 pl F.

304 45 cm. length. For what concerns the whole length of the spear, the wood fragments attached to the same suggest a total length of 1 m. and an half (pole and head together). It was directly put in the wood pole, without rivets. S. Schwarzer J.K., Arms from an eleventh Century Shipwreck, in Graeco-Arabica IV, 1991, pp. 327-350, p. 329, fig. 5. The armament discovered in the eleventh century shipwreck of Serce Limani, always more considered a Byzantine ship instead that a Muslim one, is unique for its importance in the study of the medieval weapons of that age in the Mediterranean world. It includes 50 javelins, 12 spears, two axes, fragments of 3 swords, with some of these typologies never recorded in any western context.

48

types of 10th cent. Central Europe, the type is practically identical to that one represented in the hands of Goliath in Studite Psalter Ms Add. 19352, folio 182,305 confirming its use in an East-Roman context.

The circular shield is represented in the source as a East-Roman skoutarion306 of framed wood, with what seems to be a blue-metallic edge 1-2cm. thick on the external surface. We have reconstructed it on the internal side riveted by bronze nails such as those found in Garigliano307 (fig. 15 n. 24). It is widely convex, arched in front and without an umbo; the surface is covered by a surface dyed olive-green in the median band and red-leather on the top, without metallic garments, which reminds us of the use of leather or coarse, thick donkey hide308. It was maybe provided with a carrying strap, a shoulder belt slung over the left shoulder diagonally on the upper part of the body, to carry the shield in a way not to tax or to limit the carrier’s hands in their movement (fig. 15 n. 24). In the medieval greek lexics this “chain of the shield” is called "τελαμν" like in the ancient greek309. We can suppose the presence, in the inner side of the shield, of shorter hand-grips for hand and fore-arm of the carrier, called οχανον (ancient πορπαξ)310. By means of the latter you can handle the shield or carry it if not provided with shoulder-strap. A very fine example - used in our reconstruction - can be seen in the Goliath represented in the miniature of Codice Parisinus Graecus 139.311 The diameter of shield of the “Lombard” warrior, judging from fig. 14, is about 3 spans (70,2 cm.) as described by Sylloge Tacticorum for πελτασται and light Cavalrymen312.

Interesting details reveals the analysis of the clothing, mantle, tunics, pants and boots.

In the Exultet the coarse linen cloak (sagion) is worn in a transversal way around the chest, according to the typical East-Roman fashion ; of quadrangular-shape, it is knotted on the back a little under the left shoulder. The way of wearing the cloak wrapped around the chest or the body was typical for soldiers and workers since antiquity: it generally was used

305 S. Nicolle, Arms and Armour, p. 35 fig 33s and note 68 above.

306 For the different terms employed for the shield in medieval Greek lexicon, s. Kolias, Waffen, pp. 88-96.

307 See note 99 above.

308 See note 98 above.

309 Suda, Lexicon, IV, 517 ; Pseudo Zonaras lexicon, col. 1716 ; Etymologicum Magnum, 750, 25 ; s. Kolias, Waffen, p.120 note 166.

310 See note 107 above ;

311 Folio 4v; s. Heath, Byzantine Armies, p. 33.

312 Sylloge Tacticorum, 38 ,6 ; 39, 8 ; s. Kolias, Waffen, p. 110.

49

by all the people who were accustomed to come to blows313.

The man wears two tunics: a light undergarment, probably a καμιςσιον314, in an ochre dyed linen, and a superior cotton, felt or silk garment, who could be identified with the so called armilausion,315 or a kind of padded himation worn under armour. Under the cuirass the soldiers wore special garments, to prevent the body from direct contact with iron or other coarse materials or armour and to make it easier to wear it. So at least you could deduce from the text of Anonymus de re militari of the 6th cent., which can be applied to later ages. He says that an important factor for the equipment’s effectiveness should be its distance from the body: "It should not be worn directly over ordinary clothing, as some do to keep down the weight of the armour, but over a himation at least a finger thick. There are two reasons for this. Where it touches the body the hard metal may not chafe but may fit and lie comfortably upon the body. In addition, it helps to prevent the enemy missiles from hitting the flesh because of the iron, the design, and the smoothness, but also because the metal is kept away from the flash." (Anonymus Peri Strategias, 16, 20-27)316. Under-garments of this kind (ιματια) formed a heavier weight for the soldiers, but protected them from wounds caused by their armour and offered a more consistent protection. Furthermore these undergarments were not only worn under the metal armour, but also, as in this way, under the leather fabric of the lamellae, so that their defensive function takes on a bigger importance.

We know from tacticians317 that in 10-11th centuries the Roman infantrymen wore padded tunics made of felt, cotton or coarse silk; the καβαδια of the infantry are recorded as wearing an outer protective layer318, over the armour or even instead of it, but this does not exclude that under cuirass tunics, made as well of padded material or kentoukla,319 were worn under the armour as shown in the pictorial sources.

We should verify if the padded tunic under armour here worn is to identify with the kind of tunic called αρμιλαυσιον. The use of this tunic by the infantrymen in the Roman army is attested

313 S. Pio Franchi de Cavalieri, Il Menologio, folio 3 (Joshua) p. 4. note 3; for other examples of mantle rolled up the body in 10-11th cent. Byzantium s. the Joshua Roll, in Heath, Byzantine Armies, p.5, 28, 30; the Goliath in Cod. Gr. 17 of Marciana, in idem, p.37.

314 About καμισιον s. note 138 above.

315 De Cer. II, 670; s. Reiske Commentarii pp. 341, 792-793; Du Cange, Glossarium, col. 123 : “...a men wearing a yellow- red-scarlet armelausion, quadrangular and padded...” Cfr. Martyrium S. Bonifatii and Paulinus, Ep. XVII, 1, “...cum armilausa ruberet...” in Pio Franchi de Cavalieri, Come andavano vestiti ed armati i milites, p. 225 n.3. In De Cer. I, 352 this dress is mentioned for the charioteers of the factions in the circus, who should have a padded dress.

316 Translation of Dennis, in Three Treatises, p. 55.

317 Nikephoros Phokas, Praecepta Militaria, I, 3; Nikephoros Ouranos, Taktika, 56, 3; Sylloge Tacticorum, 38, 4. 38,7;

318 On the argument s. also the interesting article of Walker G., Byzantine military coats, in Varangian Voice 45, pp.17-21

319 See also Kolias, Waffen, pp. 54-55 and note 136 ;

50

since the 6th century by the Strategikon of Maurice320. Maurice said that the infantrymen “... should wear either Gothic tunics coming down to their knees or short ones split up the sides ...”. On this occasion Maurice does not speak of a tunic which should be worn over the armour, but of the normal kind of tunics worn by soldiers also under the armour. The description given by the contemporary Isidorus of Seville about this tunic is the following: “… armelausia are so called by the people, because they are cut and open front and back, but closed only on the arms, i.e. armiclausa, missing the letter C…”321

The word could well come from the tunic worn in the Roman army by Germanic infantrymen, tunics which were seen by Isidorus with his own eyes so that there is no doubt about his description322. Substantially there were tunics of two types: or επωμιs, i.e. scapulare, covering the shoulders until the elbows ; or sleeveless, worn as the first over a inner tunic, both worn under the cuirass323.

In the 10th cent. this kind of tunic could well have maintained its original form, even though, as the other padded tunics worn by the army, its function should be that of a garment worn under or instead of the armour.

The large sleeves of the tunic hide partially heavy gold embroidered cloth cuffs on the wrist of the καμιςσιον; these are covered by silk straps, which we have reconstructed from specimens coming from South Italy, anterior to 1085 and obviously of Byzantine influence324.

On the legs the miniature shows linen and close-fitting trousers (τουβια); over the warrior dresses other simple high footwears of padded material, probably without flap, arriving till the thigh and very similar to those of Basil II in cod. Gr. 17, but of red-brown colour and with a lightly laterally flared, probably a local version of the Byzantine boot (plate 1C). I suppose we are dealing with the kind of footwear called μονοπλα in the sources325, generally very often represented as infantryman boot

320 Strategikon, XII, B2; we follow the translation of Dennis.

321 Isidorus, Origines, XIX, 22: “… armelausa vulgo sint vocata, quod ante et retro divisa atque aperta est, in armistantum clausa, quasi armiclausa, litera C ablata …”

322 Reiske, in his commentary, describes the armilausion as a kind of military coat which goes down covering the lower abdomen and sleeveless, having wide holes or openings for the arms. The origin of the dress is adscribed to the German elements in Roman army too, but the etymology armelausia or armelos should mean a garment with out arms or may be without forearms.

323 The image of the so called gothic belted tunics mentioned in the same passage of Maurikios offered by the 6-7th centuries art show as they were worn or alone or under cuirass : s. for instance Daim, Die Awaren, pp. 20-39, figg. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 19 ; the same should be for the armilavsia, “split on the sides”, Aussarres classifies the αρμιλαυςσιον as “...a close tunic, fitted to the body...” p. 58.

324 Various, I Normanni, popolo d’Europa, 1030-1200, Roma, 1994, p. 425 fig. 19 ; cm. 20x5.

325 Praecepta Militaria, I, 3 ; Nikephoros Ouranos, Tactica, 56,3 ; s. Kolias, Waffen, p.72-73 ; Kukules, Vios, IV, 409 ; Mc Geer, Showing..., p. 205.

51

in the representations326, normally of padded material and arriving to the knee and also upon it.

326 Examples from the Matritensis in folio 67r, (Kolias, Waffen, pl. XXVIII/1), from Cod. Ath. Esphigmenou 14 in folios 417, 418r in Treasures, II, fig. 405, 406, 407 ;

52

Dr. Raffaele D’Amato