Amazon Audible Gift Memberships

Amazon Audible Gift Memberships Amazon Audible Gift Memberships |

Date 1552 1552 1556Halberds etc 4 29 19 Firearms 183 69 210 Crossbows 499 506 223 ---- ---- ---- Totals 686 604 452 |

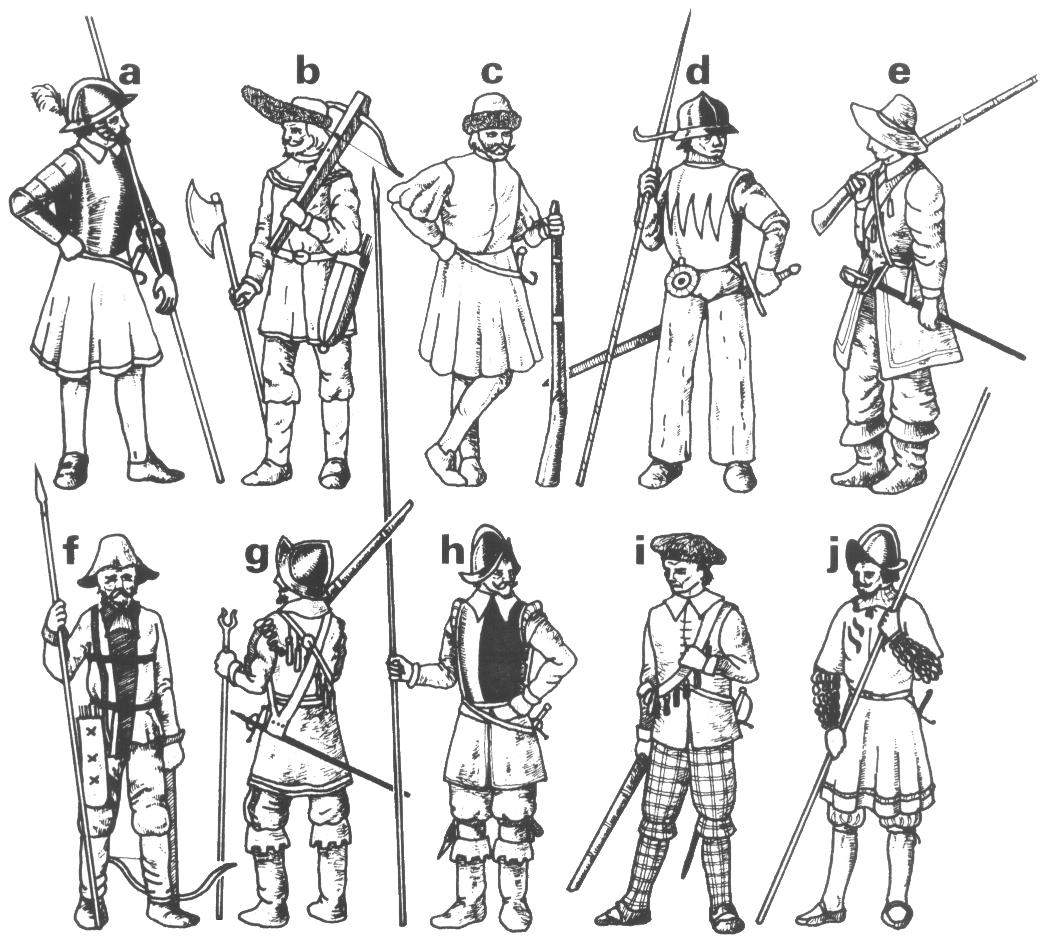

a pikeman of Erik XIV's reign in half armour. b crossbowman of the earlier 16th Century. c arquebusier of Erik XIV's reign. Note widely worn fur-trimmed hat. He may be wearing a 'jack'. d Swedish soldier of early 16th Century. He wears a pot helmet and may have a breastplate. His odd trousers look almost like cowboy 'chaps'. As well as his peculiar 'knavelspjut' he bears a very large sword - probably a two-hander. e 30 Years' War musketeer wearing a very wide skirted buff coat, trimmed in red, and very floppy boots. f early 16th Century soldier with spear and crossbow. Felt hat, trousers and boots black, coat white with green trim edged red, leggings white, quiver brown. g musketeer of Gustavus Adolphus' period. Sleeveless buff coat, trimmed with ribbon, and boots. h pikeman of the same period in morion and corselet. He wears a long-skirted buff coat and winter boots. i Scot in bonnet, thin trews, and sleeveless buff coat. j pikemen, probably end of 16th Century although frilled sleeves seem to have lingered among the Swedes as late as the 30 Years' War. |

k 'Swinefeather' or Swedish Feather. Note attachment for resting musket barrel. |

|

Previous: Part 19 - the Dutch army Next: Part 21 - the Swedish army (continued) Return to Contents of Renaissance Warfare by George Gush (Airfix Magazine Articles) See also Swedish Armies of the XVI Century |