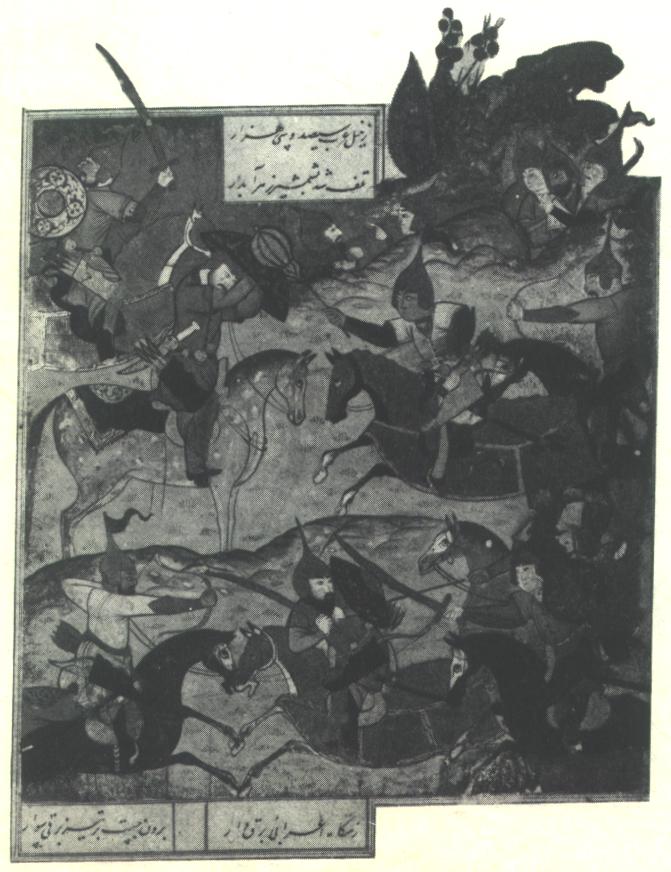

The Tartar armies, at least in Western Asia, were entirely cavalry, except that the largest khanate, that of the Crim Tartars in the Crimea, could call upon 800 musketeers from the Volga Germans when required.

Tartar dress was most often of black sheepskin (wool outward), with hats of the same, or shirts and ankle-length kaftans like the Russians, but buttoned on the left instead of the right, probably with linen breeches and half calf length red or yellow boots. However, they were anything but uniform in dress (save in general grubbiness, if European witnesses are to be believed!). Though fur-trimmed hats were common, many wore white cotton turbans, and indeed officers and leaders usually imitated Turkish dress, often including helmet and mail of Turkish, Persian, or Indian make. The protection of their followers, however, was usually limited to a round or semi-rectangular shield.

They were horse-archers first and fore- most, all carrying the composite bow. By no means all had sabres; other weapons included lassooes, and spears like European boar-spears; a very few had pistols, but in general they lacked firearms, even in the 17th Century. In tactics they were 'irregulars', using deep but loose formations, and relying on mobility and envelopment, their horsemanship allowing them to fire accurately when fleeing, or when galloping in circles, a tactic often adopted. Like Red Indians they would sometimes evade return fire by hanging down the side of their mounts by one hand and one leg!

However, their armies were far from disorganised mobs. The full army or 'orda' was divided into corps of several thousand, known as 'Czawul', which in turn were sub-divided into groups of 20 standards (a total of 800 men). An Aga commanded the Czawul, a Bey the smaller group, and the different sections of the army were kept in communication by despatch riders and directed by pipe and horn signals, each officer being accompanied by a piper. The traditional horsetail standards were also used for signalling orders, and the Tartars are said to have kept very good order so long as their unit commanders survived.

Wallachians etc

After the battle of Mohacs (1526), most of Hungary fell into Turkish hands, but Transylvania, Moldavia and Wallachia (today making up Roumania) were left as semi-independent states in a 'no-man's-land' between Turks, Poles and Austrians. Wallachia was generally a Turkish satellite, but 20 standards of Wallachians served in the Polish forces, and their princes or Voivodes sometimes fought the Turks - Michael the Brave winning a notable victory over them at Calugareni (1595). Wallachian armies of this period were entirely of cavalry, mainly nobles, lightly equipped, with spear, shield, sabre and often bow, occasionally replaced with pistols. A Polish source says they were very brave, but great looters!At Calugareni the Wallachians had the aid of Cossack and Transylvanian contingents, and Christopher Lee fans in the wargames fraternity might fancy having a Transylvanian army! The Princes of Transylvania fought for and against most of their neighbours at one time or another and were involved in the early stages of the 30 Years' War. Unusually for the area, the Transylvanian nobility got on fairly well with the peasantry (apart from Count Dracula, I presume) so that their army included infantry as well as the traditional levy of mobile cavalry. After 1606, the Princes established landless wanderers - 'Haiduks' - on holdings along the Turkish frontier, on military service terms like the Austrian 'Grenzers'.

By the 30 Years' War, Bethlen Gabor had a small standing army of infantry with firearms (and possibly pikemen also). Cavalry would probably have included mailed lancers and light horse-archers, but apparently not the plate-armoured men-at-arms who had formed the spearhead of the old Hungarian army, up to Mohacs.

Hungarian costumes of the period have been illustrated in earlier articles (Imperialists, Poles) and those in the Polish army were actually Transylvanians, introduced by Stephen Bathory, Voivode in 1571, who got himself elected king of Poland. By the early 17th Century, Hungarians already used red, white and green flags, but I don't know of what pattern.

I would like to acknowledge with thanks the assistance of Roman Olejniczak in the preparation of part of this article.

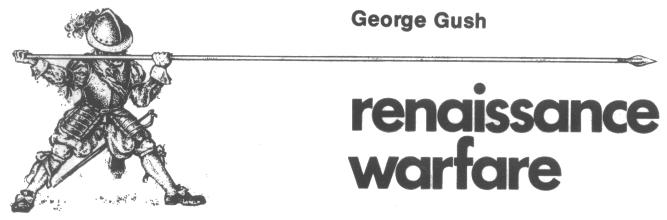

Illustrations

a Persian light cavalryman, 17th Century (could be Turcoman, Tartar or similar). Shows shape of usual quiver. This one has green cap, trimmed with brown fur; scarlet coat with gold frogging; green sash; black boots (note high heels which seem to be usual with Persian horsemen). Harness red with gilt fittings. Saddle cloth green with red fringe and decoration. Quiver black with gold patterns and purple edge. Girth yellow. b Persian 16th Century trumpeter. Wears a common Persian white turban, with one red and two grey plumes, plus decorated clothing which was not exclusive to musicians. The trumpet could also have a sharp 'step' in the middle. A kettle-drummer would be similar. c Persian 'halberdier', 17th Century. He might well be some kind of guardsman. He has a felt hat and carries an axe of very characteristic shape. Hat red, crown grey, plumes black; black and white shirt; purple coat with black frogging; tight green trousers; white 'socks'; brown shoes; red sash. d Persian artillery, early 17th Century. Gun looks rather primitive, but this may be due to the original eastern artist. The pioneer is of interest with his typical felt hat and 'entrenching tool'. The other gunner wears a type of lagging which could replace 'puttees' on other Persian foot. e and f Persian musketeers, 17th Century. Felt hats again of types often worn by Persian foot throughout our period, as are the grey-white 'puttees', white socks and black shoes. Persian musketeers replaced the bandolier of Westerners with the envelope-shaped pouches shown. Musketeer on left (e) has black hat, crimson coat, red and silver waist sash, grey breeches, red strip at top of 'puttees', black powder horn on gold cord, black scabbards with gilt fittings, and gilt buttons. Royal Guard on right (f) has grey-brown hat with crimson binding and yellow feathers in gilt holder; light green coat, crimson shirt, and scarlet trousers. Trim on upper jacket is brown with red edges (could be fur). Gun may be flintlock as Shah Abbas had some 'fusiliers'. Other colours as for 'a'. g Persian musketeer, late 16th or early 17th Century. Elaborate turban. Sabre slung very high from shoulder belt, with one strap at front and rear. Usual 'envelope' pouch below powder horn. Stripes on musket butt, which are white, seem to be characteristic of Persians. h Persian cavalryman, 16th Century. Likely to have full mail under his long kaftan, though only vambraces show. He is using a short javelin, the case for which can be seen beneath his quiver. His Scottish-looking headgear may be associated with the Quizilbashes, as it is often seen on the Shahs of this period and their followers. It consists of a red turban (purple for Shah Abbas) with a protruding piece and plume, and a white cloth with red lines, tied tightly round it. The large saddle cloth, round saddleflap and two cords across horse's chest are typical. He would also carry light lance and shield, and could have helmet and aventail like 'i'. i Persian cavalryman with typical spiked helmet with two plumes and adjustable nasal plus mail aventail, cut in points at bottom. He (rather unusually) wears his mail uncovered, allowing us to see the 'Char Aina'. His mail leggings with knee and foot protections are also unusual, though authentic. He carries light lance, sabre, bow in case, quiver on other side, mace at his saddlebow, and typical convex shield with pronounced rim and four bosses. Horse bard covered with cloth; plate head defence.

[a, c, e and f are based on Dr. Kaempfer's Album of Persian Costumes and Animals]

[g is based on Emperor Timur’s Ambassador in the Presence of Sultan Bayezid Yıldırım (‘the Thunderbolt’). British Library. Ms. Or. 5736, folio 172b]

Persians, early 16th Century. The tall pointed helmets were later supplanted by the type shown on drawing 'i' in previous illustration (British Museum). |

Shah Abbas' own helmet - typical of Persian 16th Century and later helmets. Note spike, two plume holders, adjustable nasal and mail aventail cut in points. |

Key to drawings j, o and p are Tartars, 'p' has a turban, probably white, and carries a spear and broad sabre (note suspension cords, usual for easterners). The flag is from a contemporary print, though Tartars normally used horsetails. 'o' is probably a chief (note long plaits) and wears a fur-trimmed hat. His long kaftan has its skirts tucked back, showing tight hose and boots. He has a horseman's war hammer and a Turkish-type shield (note ring and cord for slinging it on back). 'j' has a sheepskin cap and another sheepskin tucked through his sash, plus sheepskin boots. Horsetail seems to be pushed through a sort of 'woggle' but may be knotted. k and l are Mamelukes, based on later drawings but probably giving a fair idea of them during our period. 'l' has blue and white clothing, yellow shoes and red and white sash. His brown beehive-cum-coconut hat may be rawhide, and was also worn by Moors and Stradiots. Plumes white. 'k' is dressed in white with a red cap in his turban and red stripes on cloth trapper on horse's hindquarters. The lance pennon is blue with a white crescent. Both 'k' and 'l' have Turkish-style shields of the near-rectangular type, and are likely to have worn mail under their outer clothing. m Transylvanian/Roumanian peasant infantryman, early 17th Century. Cap is probably sheepskin, cloak could be fur. Note sandals and binding round ankles. n Arab light horseman from a 17th Century picture, but could be 16th Century too as costume did not change in the east as quickly as in the west. The rather peculiar headdress or hood is black, robe black and white, harness and breast-strap brown leather, fringe on lance red.

[k & l appear in the Mamluk section of Recueil de tous les costumes des ordres religieux et militaires by Jacques Charles Bar, Paris, 1778 except for the trapper. Sourced from: for k Illustrations de Diversarum gentium armatura equestris, Abraham de Bruyn, 1577; for l Hopfer & ultimately Mamelukes in 'Süleyman and his cortege', by Jan Swart van Groningen, 1526]

Top Persian Bazabund or arm protection. Shah Abbas' period, possibly even his! Note mail 'mitten' and splinted armour for wrist (British Museum).

Left Mameluke shield. Right 15th Century Mameluke helmet, designed to be worn over a turban (Tower of London Armouries).

|

|

|

Persian flags (horsetails also used). a is purple with gold 'lion' and foliage (early 17th Century). b many possible patterns including green with gold centre or purple with silver centre. Gilt ribbon. Mid-17th Century. c 15th Century. Colours include green/red, blue/red, blue/yellow. Stripes on staff red or blue and white.

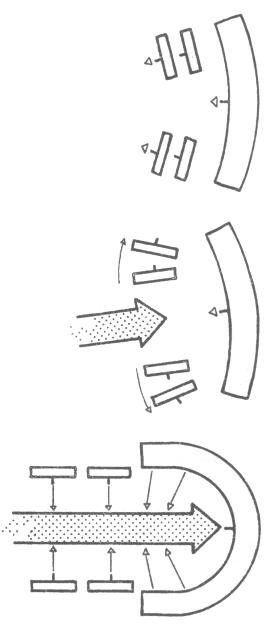

Tartar tactics 1 main Orda at rear, four Czawuls out in front. 2 enemy attack, Czawuls give way, wheeling to flanks. 3 enemy penetrates, centre gives way, wings encircle enemy, advance Czawuls return to attack enemy flanks and rear (Roman Olejniczak). | |

Transylvanian standard. This device was used by Stephen Bathory (who became King of Hungary). Colour of device was white on blue ground. |