Part 10: The Turks. Part 1: the Spahis

by George GushFROM WESTERN EUROPEAN troops we now turn to a quite different kind of force, the vast hordes of the Ottoman Empire. The tide of Turkish conquest was still on the flood when our period begins, reached its highest mark with the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-66) but, as his armies were halted at Vienna in 1529 and Malta in 1564, the long slow ebb began. However, even by the late 17th Century the Turks could still menace Europe, as the siege of Vienna in 1689 showed.

The Turks were unique in the 16th Century in maintaining large regular forces, paid, disciplined, living in barracks and enjoying such 'modern' benefits as pensions and paid leave, and with the added stiffening of religious enthusiasm. Surprisingly, these regulars were not only slaves in official status but also non-Turkish, being recruited by the 'Devschirme' - a tribute of male children levied from the Christian subjects of the Empire by the Sultan's officials. Brought up in the Imperial Household as ajenioghlanlar (recruits) or (the best) as red-uniformed ichoghlan (palace pages) the children became fanatical Moslems, cut off both from the Turkish population (they were forbidden to marry), and, by religion, from their parents' people, with loyalties only to their corps (they manned not only the regular army but palace and government also) and to the Sultan. It certainly worked, for European contemporaries all agree on the great superiority of the Turkish regulars - as one remarked 'On their side are the resources of a mighty Empire, strength unimpaired, experience and practice in fighting, a veteran soldiery, habituation to victory, endurance of toil, unity, order, discipline, frugality and watchfulness' - not qualities common in European forces of the period.

The Turks also held a technological lead over Europe at the outset of the period in the very large scale use of firearms and the possession of large State arsenals and even a highly-mechanised gunpowder factory!

Alongside this the Sultans had the resources of a huge and teeming Empire, and the combination of the elite regulars with semi-feudal levies and vast swarms of unpaid pillagers gave the Ottoman armies their peculiar and unique character For the military modeller they provide some of the most exotic and colourful subjects of this colourful era, for the wargamer a force whose composition and tactics contrast completely with those of European armies of the period - though be warned and pick a big table if you want your Turks to win! For those who wish to be strictly historical, the Turks in our period fought the Knights of St John, Mamelukes, Abyssinians and Portuguese, Spanish, Venetians, Imperialists, Hungarians, Persians, Druses, Poles and Muscovites, so there is no lack of adversaries!

Spahis

Spahi simply means a soldier, but in this case a heavy cavalryman. The Sultans had basically two types of Spahi - the paid regulars of the Household Cavalry ('Spahis of the Porte') and a larger but less well-trained body of 'feudal' cavalry.The Household Cavalry formed six regiments, divided into squadrons of 20 men each. The four oldest were known as 'Boluks' and consisted of two regiments of Olufeci (or paid men) and two of Gureba (strangers). The latter were the only regulars not recruited by the 'devschirme', but as their name indicates they were non-Turkish, being recruited from Moslems from outside the Empire. In the early 16th Century these four regiments were all 500 strong.

The newer, larger and more honoured regiments were the Spahis, who formed on the Sultan's right in line of battle (3,500 strong in the early 16th Century) and the Silhidars ('swordbearers') who formed on his left (2,500).

Under Suleiman the Magnificent the total of the Household Cavalry was increased to about 12,000, and according to some sources they were accompanied by armed and mounted slaves who could bring the whole number as high as 30,000.

The 'Feudal' Spahis held estates on a non hereditary basis in return for military service. Those with the smallest estates - 'Timariots' - had to report for service with horse, armour and arms, those with bigger holdings had to bring a retinue of up to 18 'Jebek' (mounted men-at-arms) with them.

Weapons for all these cavalry comprised a light lance, usually painted green, with a pennon, a composite bow carried in a case on the left and a quiver of brightly-painted arrows on the right - both cases were highly decorated. When the how was in use, the lance was held between the rider's thigh and the saddle, point to the rear. A jewelled scimitar was also carried and a short steel mace hung from the saddle bow. In contrast to the Turkish infantry, the cavalry considered firearms very dirty and dishonourable and virtually refused to carry them until the late 17th Century. A shield was strapped to the left arm; like most Eastern cavalry shields this would be round and up to about 30 inches in diameter; in the early 16th Century it could be formed of cane rings bound with gold or coloured thread around a large steel boss, later it would probably be all-steel, often painted or engraved.

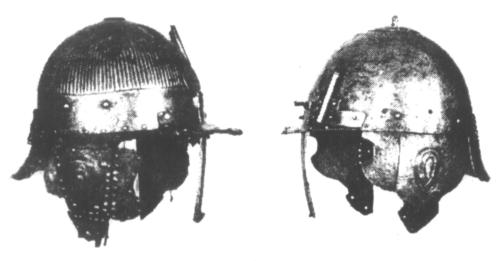

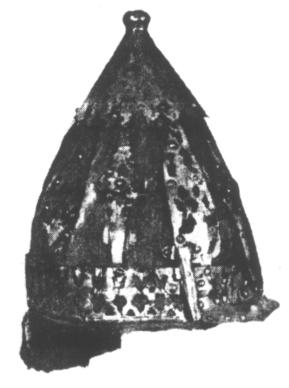

Armour was usually worn in battle, and the typical types are illustrated; it was normally reinforced mail, and horses could also be protected, especially in the earlier part of the period, laminated, mail and leather armour all being used, with plate for the face. Cloth trappings might cover horse armour. There is a splendid picture of a Turkish horse armour in Arms and Armour by Aldo Cimarelli (Orbis Books) which has many other pictures from this period.

The dress of the Spahis was rich in the extreme; contemporaries mention cloth of gold and silver, as well as scarlet, violet, dark blue and green, with gold embroidery, for the Spahis of the Porte; jackets or caftans worn over armour often had hussar-style lace on the front, a typical Turkish decoration; trousers were baggy, boots normally yellow. When turbans were worn they were always white, with a red or purple central cap and black feathers. Cloaks were often worn and were green and yellow for one 17th Century Household unit - some accounts seem to imply the wearing of uniform colours by the Household units, but this would certainly not be the case with the feudal cavalry. Like the lighter Turkish cavalry the latter probably favoured green or blue caftans. Turks also wore white, yellow, violet and mouse-colour, but black was avoided and purple considered unlucky in battle. Horse trappings were extremely ornate, with silver fittings, jewellery, and very large, fringed, saddle cloths.

The Turkish 'heavy' cavalry could not usually stand against the heavier European Gendarmes and pistoliers, but would either rely on a screen of light cavalry to break up the Europeans' order, or use their mobility and archery against such lumbering adversaries.

Light cavalry

Every Turkish force was surrounded by vast clouds of irregular light horsemen, giving them a great advantage in reconnaissance and intelligence. Nearly all would be irregular light horse-archers with composite bow and scimitar, though some might also carry spears.'Akinjis' (scouts) were usually Turks, in turban, caftan and baggy trousers - 30 or 40,000 of them could be called on, fighting for plunder rather than for pay.

Next in importance were the Tartars, descendants of the Mongol hordes, fierce horse-archers on shaggy ponies. The eldest son of the Khan of the Crimean Tartars was always a hostage at the Sultan's court to ensure the alliance of these fellow- Moslems; their appearance was similar to the Akinjis, though they wore fur, or fur-trimmed, caps, and had a reputation for grubbiness, and they too were paid from loot.

Other types included Arab mounted spearmen in traditional dress, and Balkan horsemen of whom the most interesting were the 'Dellis' (mad-heads); volunteer Croat or Serb daredevils, often Christians, who often formed the bodyguard of provincial governors and the like; their headdress was a hanging cap of snow leopard skin, decorated with eagles' wings, and their cloak another leopard-skin; their shield, of the odd pattern also carried by Turkish infantry, had more eagle-wings nailed to it; their saddle cloth was a complete pelt (sometimes a lion's) and their jacket and wide breeches could be of lion or bear-skin, fur out. Their yellow boots carried foot-long spurs, and they bore mace and scimitar, as well as a very long straight armour-piercing sword slung horizontally beneath the right saddle-flap; their lance could have a small poleaxe blade below the point.

Standards etc

The Household regiments seem to have had flags - probably Spahis yellow, Silhidars red, the two Olufeci regiments red-and-white and red-and-yellow, and the two Guerba regiments green and white respectively. They were commanded by Agas.The feudal Spahis were commanded by local governors drawn from the Household; the Sanjak-Begs had a flag surmounted by a gilt ball, while their seniors, the Beglar-Begs, like all high Turkish officers, had horsetail standards (one tail or 'tug' for a Beglar-Beg, four for the Grand Visier or army-commander, seven for the Sultan). The horsetails were white, decorated with red and blue ribbons and carried on red poles surmounted by a gilt ball; Suleiman the Magnificent's also bore a great silver disc and a gilt crescent. The Tartars too traditionally carried horsetail standards.

Armies

Normally had more cavalry than infantry, and the following (modern) estimate for the Turkish army at Mohacs (1529) gives a fairly typical make-up: Infantry - 2,000 Janissaries, 5,000 local levies; Cavalry - 7,000 Spahis of the Porte, 10,000 Asiatic feudal Spahis, 15,000 European feudal Spahis, and up to 20,000 Akinjis.A typical disposition for a Turkish army is indicated by the diagram of their army at Chaldiran (1514, against the Persians) though here they had 55,000 infantry to 85,000 cavalry.

Infantry (including the famous Janissaries) and other arms will he covered in the second half of this article.

Illustrations

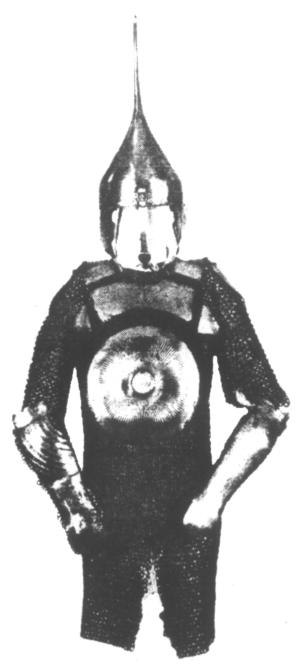

15th-16th Century Turkish armour with Turkish-converted Persian 'Kulah Khud' helmet (Tower of London Armouries). |

Another type of Turkish 16th Century armour (Tower of London Armouries). |