Try Amazon Audible Plus

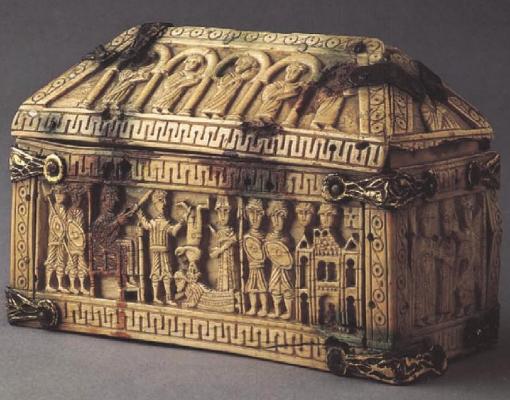

Casket

Northern Spain, 8th-10th century

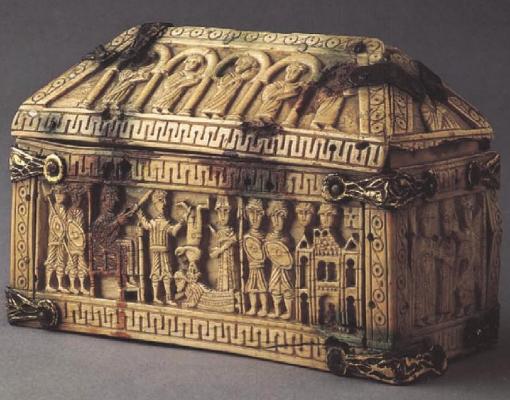

Larger details of The Judgement of Solomon, Spanish Casket, 8th-10th century |

Larger details of The Judgement of Solomon, Spanish Casket, 8th-10th century |

pp.141-142 The Art of Medieval Spain AD 500-1200, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York:

Casket

Northern Spain, 8th-10th century

Ivory and gilt-copper alloy

3½ x 4⅞ x 2⅛ in. (9 x 12.5 x 6cm)

Glencairn Museum; Bryn Athyn,

Pennsylvania (04.CR.49 a,b)

According to tradition this remarkable miniature casket once belonged to the treasury of the northern French abbey of Saint-Evroult-d'Ouche (now destroyed), which in the thirteenth century received inheritances from Navarre. The casket is formed of ivory panels joined with ivory pins and reinforced with gilt-copper alloy clips bearing faceted or chip-carved designs. The panels making up the casket illustrate episodes in the life of King Solomon. On one side Solomon is shown entering the city of Gihon on a mule (I Kings I:33). Youths holding palm branches in acclamation of Solomon's arrival make clear that the image is appropriated from-and intended to be a typological reference to-Christ's entry into Jerusalem. On one end of the casket is a scene that very likely depicts the anointing of Solomon by the priest Zadok and the prophet Nathan (I Kings I:45): Solomon, wearing a crown, is flanked by two figures; the one on his right appears to have wings. (Alternatively, the crowned figure and the one to his left have been identified as Solomon and Sheba.) On the other side of the casket the Judgment of Solomon is represented: the king is enthroned behind a soldier who at his behest is about to divide a child in half in order to determine which of the two women claiming him is his mother (I Kings 3:16-28). A frontal elevation of the temple of Jerusalem is depicted at the right of this scene, while, on the opposite end of the casket there is a longitudinal two-story elevation of the same structure, presenting an unusual architectural rendering of the celebrated temple. The imagery on the top of the casket consists of arcades inhabited by unidentified figures dressed in long robes and in some cases holding books; two of the arcades are filled with processional crosses on stanchions.

The subject of the Judgment of Solomon may have been intended as a visual allegory in which the two harlots are possibly a reference to Ecclesia and Synagogue. The parallel established between the Meeting of Solomon (and Sheba?) and the greeting of Christ in Jerusalem seems deliberate, with the temple of Jerusalem functioning visually as a link between both events and the holy city. The intentional ambiguity of the entry scene on the casket is analogous to an image on a Burgundian buckle of the sixth century that, like the subject of the casket, has been identified as the entrance of a royal personage into Jerusalem.1 The fact that the buckle and casket scenes include a ruler, an angel and a welcoming crowd suggest, almost a priori, an adventus-kingship program: the ceremonial of the king's liturgical reception into a city reflecting Christ's entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday.

The reinforcing bands of gilt-copper alloy with chip-carved patterns are not original to the casket but were added at an early date. Chip carving was universal in Europe in the early Middle Ages (from the sixth to the eighth century), yet, except in Scandinavia, by the tenth century the technique had all but disappeared.

The function of such a small casket-usually thought to be for relics-remains unclear It may have held the chrismals used for the rite of baptism or, because of its royal themes, for coronations. The date of the casket is equally uncertain. According to tradition it is believed to be Mozarabic, dating to about the tenth or eleventh century. The architectural decoration, with its emphatic arcades composed of horseshoe arches, recalls that of San Cebrián de Mazore or San Miguel de Escalada. However the miniaturization reduces the images to a schematic biblical structure as found, for example, in the illuminations in the Escorial Aemilianensis (cat. 83) and Vigilanus manuscripts. The figure style of the ivories and the book illuminations is also comparable, with both clearly reflecting Visigothic models. Unfortunately without surviving Visigothic manuscripts one can only assume that the Mozarabic books are near copies of such earlier works.

While the flat-relief carving technique, as well as the proportions of the figures-and especially their heavily articulated eyes and their overall frontality despite the profile view-echo the seventh-century capitals at San Pedro de a Nave (Zamora), this miniature casket is unrelated to any other ivory. It may be a precious survivor of Visigothic Spain transported to the north and, as such, an exotic example of Early Christian art.

CTL

1. Roth 1979, fig. 292a.