Register a SNAP EBT card with Amazon

Pictish Horseman c.685. |

‘A Woeful Disaster’

The Battle of Nechtansmere, 685 AD.

by Guy Halsall

Miniature Wargames No. 19, December 1984.

Pictish Horseman c.685. |

Introduction

"Then at last came news of a woeful disaster, a battle against the Picts in which King Ecgfrith of Northumbria and the flower of his army had been mown down." (Eddius Stephanus, The Life of St. Wilfrid, ch.44).

The 20th May 685 saw the playing out of one of the most decisive acts in the history of northern Britain. The sun rose that day over the mighty host of Ecgfrith of Northumbria as it pursued the seemingly beaten forces of King Brude mac Bile of the Picts into Angus. It set over the shattered remnants of the English army as they streamed south in rout, leaving their king, his bodyguards and hundreds of lesser men dead on the field of Nechtansmere.

It was a dramatic turn of events and one of great importance for the north. This article will attempt to show how the Picts ensnared and destroyed the army of the most powerful and feared king in Britain, giving them their independence and the most famous victory in their history.

The Location of Nechtansmere

Here we are, for once, in the somewhat unusual position of knowing where a seventh century battle took place. For years the location of Nechtansmere was a matter of some confusion. Fortunately, however, though the ‘mere’ or lake itself has dried up and the Pictish fort of Dunnichen has been quarried away, F.T. Wainwright proved beyond doubt that the battle was fought at Dunnichen near Forfar. He was even able to plot the approximate extent of the lake from observations made during particularly wet years when much of the valley bottom reverted to marsh. (1).

The Evidence

The battle of Nechtansmere was one of the great events of the late seventh century and, as such, features prominently in the literature of the period. As well as its ‘political’ importance the battle had the added attraction of being a great victory by one of the ‘Celtic’ peoples over the hated English invaders, the just deserts of a king who dared to offend St. Wilfrid, and the occasion of one of St. Cuthbert’s wise but unheeded pieces of advice and of one of his visions. Though not truly Celtic, the Picts were seen as having a common cause with the Celtic peoples proper, the Welsh and Irish/Scots, by Irish and Welsh writers. References to the battle can be found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in two almost contemporary lives of St. Cuthbert, in the Life of St. Wilfrid, in Bede’s ‘Ecclesiastical History’ (written 731), in the various sets of Irish annals, in the ‘Historia Brittonum’ attributed to Nennius, and in Irish poetry. The best summary of the information contained in these sources is that given by Wainwright (2). Very little, as ever, is written on the course of the battle but we can gather more facts than are available for many of the battles of this era and these will be discussed below.

The Historical Background

Before examining the course of events in 685 let us take a look at the historical background to the battle. Any student of the early medieval period in Britain will know that the seventh century saw a long struggle for supremacy between Northumbria and Mercia. This conflict is a predominant feature of the history of the northern realm. No less than six of her kings were killed by southerners between 616 and 678.

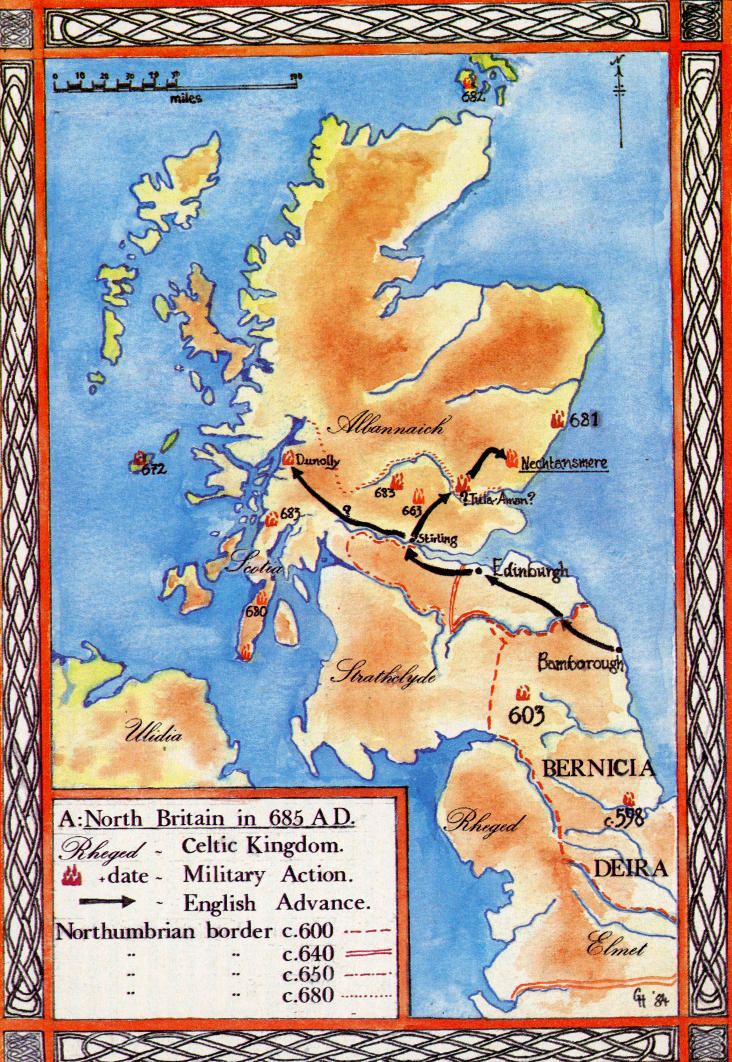

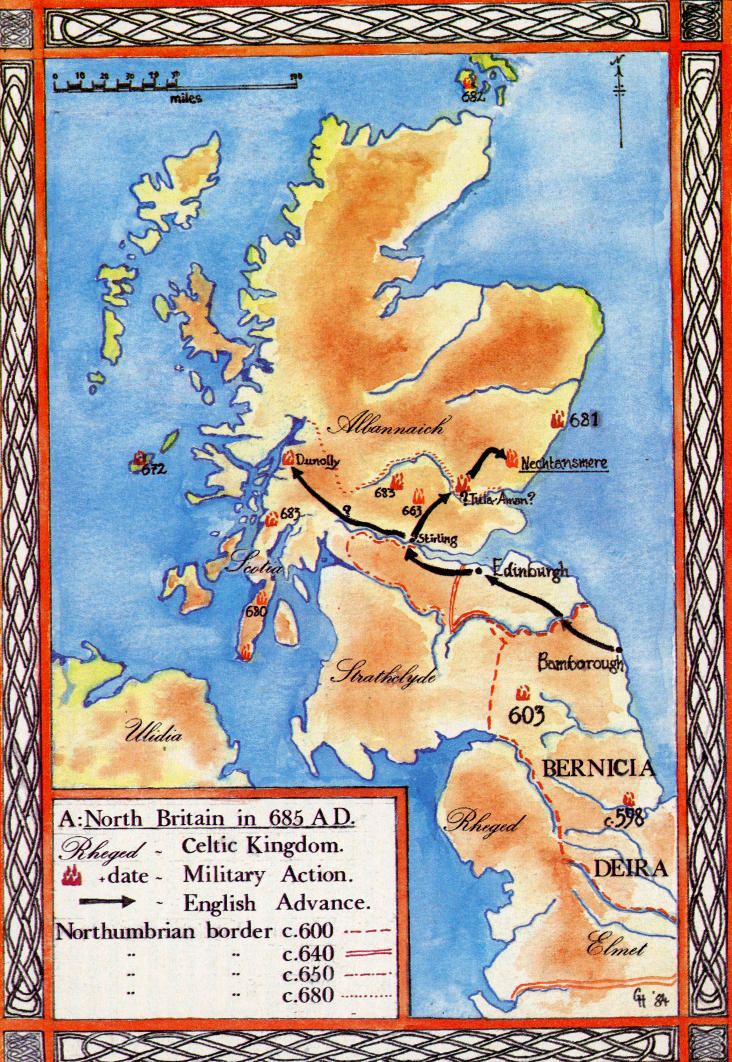

This titanic struggle in Lincolnshire, Yorkshire and the North Midlands should not obscure events in the far north, no less important in the development of Britain. The great victory at Degsastan in 603 had ended Scottish capacity to intervene in north Britain and thereby opened the way for Northumbrian expansion. The advance into Lothian was slow but remorseless, even if the sources are almost silent about it. In 638 there occurred the siege of Edinburgh. This probably represented the final blow in the absorption of Lothian and Manau Gododdin. Thus about forty years after the princes of the latter realm had had their army crushed at Catraeth, the sons and grandsons of the victors of that battle stood in the former British capital and looked northwards over the Forth to the lands of the Picts. By the 650s the Northumbrians may have been in control of Stirling and the only crossing point of the Forth (3). There the advance stopped temporarily for the Picts were already almost a subject kingdom. Their ruler, Talorcan IV was a nephew of King Oswy of Northumbria, being the son of King Eanfrith of Bernicia who had been killed by Catwallon of Gwynedd in 633. Talorcan defeated the Scots at Strath Ethairt in 653, killing Duncath, their king, and extended the authority of the House of Ida into Argyll. He died in 657 and Oswy took the opportunity to bring the lands of the southern Picts, Dalriadic Scots and Strathclyde Welsh under his control, making him the most powerful ruler that Britain had seen since the days of the Romans (he was, until 657-8, the King of Mercia as well). The conquest of Strathclyde may have begun as early as 641 when the annals of Ulster record a battle between Oswy and ‘the Britons’ (4). The English progress met with some resistance, it seems, for the Picts continued to elect kings in the north of their lands and the Scots apparently maintained a ‘war of independence’ in their own lands. In 663 the Ulster annals record the battle of ‘Luth-feirnn, i.e. in Fortrenn’ (Fortrenn was a Pictish province around the south Perthshire area.) (5).

After the death of Oswy in 670 the troubles continued. The able son of a Strathclyde prince was elected King Brude (or Bridei) III of Pictland in 672, a year which saw the killing of the new King of Scots, Domangart, and the burning of one of his strongholds. In 673-4, Brude incited the southern Picts to rebel and launched an invasion of their lands. This met with disaster when Ecgfrith and a ‘troop of cavalry’ slaughtered them in battle, allegedly filling two rivers with their corpses. Though this left Ecgfrith free to deal with Mercia, the postulated border war continued. In 679 there occurred ‘the siege of Baitte’ (apparently somewhere in Scotland), the following year saw the killing of Conall, the new King of Scots, and the siege of the Pictish fortress of Dunottar is recorded under the year 681. Brude turned his attention northwards and in 682 he ravaged the Orkneys. Ecgfrith was looking north again, however, and the following year saw the destruction of the Dalriadic capital, Dunadd, and the Pictish stronghold of Dun Duirn. Could English forces have been behind these actions? In 684, with Picts and Scots in disarray, the Northumbrian king decided to extend his authority to the other side of the North Channel and sent a fleet to ravage Ireland, an action which outraged Bede and which was seen as the cause of the following year’s divine retribution. The king was at the height of his power and in the next year he gathered a large army and embarked upon the invasion of Pictland.

The Campaign of 685

The sources agree that Ecgfrith mustered a huge force for his Pictish expedition in 685. It will have included the famous Bodyguard of the Northumbrian Kings, one of the crack units of seventh century Europe, and many battle-hardened veterans of the Irish campaign of 684, of the border war of the past decade and possibly of Ecgfrith’s Mercian campaigns of 674 and 679. The army must have been mustered in Bamborough or Edinburgh as early as April. The queen was sent to Carlisle with St. Cuthbert to stay at a convent and await the king’s return, and possibly a regent was appointed. If so, it would probably have been Beornhaeth, Ecgfrith’s ‘trusty sub-king’. The campaign was not universally popular and some of the royal counsellors, notably Cuthbert, spoke out against it (or so we are led to believe). However, it went ahead nonetheless.

Ecgfrith and his bodyguards and perhaps the bulk of his troops set out from Bamborough probably in late April or early May and moved north, perhaps being joined by further contingents at Edinburgh. Some time around the tenth the Northumbrian forces will have crossed the Forth at Stirling and headed into fife. Though relying on a dubious translation of an obscure passage of the Annals of Ulster, some historians have suggested that Ecgfrith despatched a division to bum Dunolly in Scottish territory and also burnt a place called ‘Tula-Aman’, located by some at the point where the river Almond flows into the Tay. ‘Tula-Aman’ lies on the Northumbrian rout of march and it would hardly have been out of character for Ecgfrith to have reduced the place to ashes, or for him to have sent troops to harry Dunolly. (6). If we accept this translation and if we accept that Ecgfrith was behind the sieges of Dunadd and Dun Duirn we can see that the campaign of 685 is perhaps following the possible course of the suggested campaign of 683, with a two pronged advance into Dal-Riata and Pictland. This time the operation was on a larger scale and pushed further. This is, I must stress, conjectural. from the Perth area, Wainwright suggested, Ecgfrith moved up Strathmore to the Forfar district. Near Forfar, lured all the way by Brude’s retreating warriors, he turned south. At about 3 o’clock in the afternoon of Saturday 20th May 685 (the sources are unusually precise!) the English army surged over Dunnichen Hill and into an ambush . . .

The Battle

Nechtansmere was probably a confused affair, heavily at odds with some current schools of thought in the study of early medieval warfare. The English army, perhaps advancing in a column of several divisions or battles, will have followed the decoy of retreating Picts down the slope of Dunnichen Hill towards the lake at the bottom, noticing for the first time the fort of Dun Nechtan, King Brude and the main Pictish army some four hundred yards to their left! (7). A nasty shock. Brude may well have posted a force to the right of the English as well. Now the battle began in earnest. It will have taken the Pictish warriors about 3 or 4 minutes to reach Ecgfrith’s soldiers and in that time the Northumbrian ealdormen had to form the disordered mob of Fyrdsmen into a coherent body of fighting men. Already Brude’s skirmishers will have run into range and have been shooting arrows and hurling javelins into the shaken mass of Englishmen. Thundering hooves will have heralded the approach of the fierce Pictish horsemen, perhaps thrown out in wide flanking movements. The Northumbrian army was in chaos. Some troops may have continued towards the lake after the decoy, others may have tried to regain the high ground, others still may have tried to beat an organised retreat, whilst yet more may have simply milled about in confusion or taken to their heels. Those lucky enough to be mounted might have urged their steeds into motion, and taken the wisest course of action and attempted to cut their way through the lightly armoured Picts to freedom. With such a tempting prize ahead of them the Picts will not have paid much attention to the few who managed to succeed in this. The Northumbrians must have felt much like the redcoats at Isandlwana did as their pitiful company lines were overrun. In the midst of this confusion one body of men formed up and prepared to sell themselves dearly - the royal bodyguards. However, by the time the Picts reached the English most of Ecgfrith’s army had dissolved. The armour and organisation of the English were at a discount and the battle will have been largely over in a few minutes, the Northumbrian divisions being overwhelmed, pursued and cut down. Isolated clumps may have tried to fight on and joined with the bodyguards in a last stand. This took place, it seems, by the lake as the battle was usually referred to as that of Nechtansmere rather than that of Dun Nechtan. Nennius calls the battle ‘Llyn Garan’ ‘the lake of cranes’. Here, on the marshy shores, Ecgfrith and his brave warriors died beneath the axes and spears of the howling Picts. The last great king of Northumbria was thirty-nine. Some of his men did escape - we know of one arriving in Carlisle with the bad news on the following Monday. Even so, the slaughter had been terrible as our sources confirm. ‘. . . the flower of his army . . . mown down.’ (the Life of St. Wilfrid, ch. 44); ‘Ecgfrith . . . was slain together with a great multitude of his soldiers.’ (Annals of Ulster); ‘. . . he [Ecgfrith] was killed with the greater part of his forces . . .’ (Bede’s ‘Ecclesiastical History’ Book iv, ch. 26); ‘. . . he fell with all the strength of his army’ (Historia Brittonum ch. 57); ‘King Ecgfrith was killed . . . and a great army with him.’ (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle); ’. . . the king and all his bodyguards had been slaughtered by the Picts.’ (Bede’s life of St. Cuthbert ch. 27).

Conclusion

In many respects, the battle of Nechtansmere is similar to that of Bannockburn over six hundred years later. Both were fought to stave off English domination, both succeeded dramatically and both instituted a brief period of supremacy for the northern realm (Pictish in 685, Scottish in 1314). Bede states that ‘Henceforward the hopes and strengths of the English realm began to waver and decline, for the Picts recovered their own lands that had been occupied by the English, while the Scots living in Britain and a proportion of the Britons themselves regained their freedom . . . .’ Nennius adds ‘. . . the English thugs never grew (strong enough) from the time of that battle to exact tribute from the Picts . . . .’ The Northumbrian border receded to the river Carron with a ‘no man’s land’ between that river and the Forth. Both sides continued to raid one another but the Picts retained the upper hand. Brude III died in 692 but in 698 his successor defeated and killed ealdorman Beornhaeth in battle and their superiority was maintained until 710 when Ealdorman Brihtferth ‘slaughtered’ them between the rivers Avon and Carron. Thereafter, the two nations seem to have remained at peace but the death of Ecgfrith, the last great king of Northumbria, has been seen as marking the beginning of the decline of Northumbria.

Wargaming the battle

The Nechtansmere campaign provides numerous wargames scenarios. The whole affair could be constructed as a wargames campaign, the siege of ‘Tula-Aman’ could be refought, or that of Dunolly, bringing the early Scots into things. A possible holding action by a small decoy force of Picts at the crossing of the river Tay could be attempted, or, in the skirmish wargaming field, how about a clash between English scouts and the Pictish rearguard, or a game in which a group of English fugitives is confronted by Pictish pursuers or by a small Pictish contingent arriving too late for the battle? There are many possibilities, but here I will concentrate on reconstructing the main engagement at Nechtansmere.

Diagram B shows the terrain around Nechtansmere, or Llyn Garan, and the suggested deployment of the two armies. These need not be followed exactly. The forces around the symbol stone may be moved to the English left if the players decide that Ecgfrith has too little chance. Moreover, the reconstruction of events (largely Wainwright’s) is not the only one. Another theory would have the English marching in from the coast and around the northern shore of the ‘mere’, the Picts descending from Dunnichen Hill. The choice is yours and the only way to find out which is the more enjoyable as a game is to play them both. Either way the English player should only be shown the decoy before writing his orders. He must then make one move of pursuit and take a control or reaction test. The result is binding. Then the rest of the Picts visible to Ecgfrith are deployed. He may then write his order changes before his men can react to the new threat. Now the English have to take a morale test. These may overrule any order changes. Then the game goes ahead as usual.

The English army was obviously large by the standards of the age, even after the possible detachment of a force to raid Dunolly. I would give Ecgfrith 3,100 men made up thus:

Men Figures Code Troop Type Comments 300 15 A Royal Bodyguard Excellent, semi-regular, mtd. infantry in full mail with medium (6-9ft.) spears, heavy throwing weapons and good swords. 2000 100 B-D Warriors Veteran irregulars in leather armour with medium spears and swords. (2x40 figs. + 1x20 figs.) 400 20 E Peasants Poor irregulars with short spears (less than 6ft.), unarmoured. 200 10 F Archers Unarmoured skirmishers with bows. 200 10 G Javelinmen Unarmoured skirmishers with javelins. 3100 155

Up to 15 warriors may be given partial metal armour and up to 30 (10 in each division) may be made mounted infantry. All mounted infantry start the battle on horseback.

The Picts seem to have been able to summon up comparatively large forces so they were given 4,300 men made up as follows:

Men Figures Code Troop Type Comments 80 4 1 Hvy. Cavalry Irregular cavalry in helmets and mail shirts, armed with javelins and swords. 100 5 2 Companion cav. Good, unarmoured, irregular light horse with javelins and swords. 400 20 3-6 Light cavalry Unarmoured, irregular light horse with javelins and swords (4x5 figs.). 400 20 7 Decoy Unarmoured irregular infantry with medium spears. 2400 120 8-10 Infantry Unarmoured irregular foot with medium or long (over 6ft.) spears. (3x40 figs). 600 30 11-13 Archers Unarmoured skirmishers with bows. (3x10). 320 16 14 Javelinmen Unarmoured skirmishers with javelins. 4300 215

The battle is a very hard one for the English player and something of a ‘table top teaser’. If he can win — WOW! The best I have managed is to extricate the army. Even so it is usually an exciting battle with much scope for the unexpected to happen, especially if your rules make the Picts as unpredictable as they undoubtedly were.

Notes

(1) F. T. Wainwright 1948

(2) ibid. pp82-6.

(3) The campaign of 654, against Penda, involved the ‘distribution of Iudeu’, Iudeu, one of Oswy’s fortresses, is identified with Stirling.

(4) Annals of Ulster s.a.641. This could be a reference to the battle of Maeserfelth, however.

(5) In the following, use has been made mainly of the Ulster annals which give many enigmatic references to engagements and sieges without naming the antagonists. Most of these are probably Scottish or Pictish internal struggles but it is surely possible that some represent the struggle with Northumbria which was undoubtedly going on at this time. Either way it was a troubled time for the North.

(6) The passage in question reads ‘et combusit Tula Aman Duin Ollaigh.’ The identity of Tula Aman, place or person is a mystery. Hennessy translates this passage as ‘and Tula Aman burnt Dunolly’. The passage remains obscure.

(7) Here again I follow Wainwright (1948).

Bibliography

Primary sources

W. M. Hennessy. The Annals of Ulster Vol 1. London, 1887.

S. (Mac Airt. The Annals of Inisfallen. Dublin, 1977.

J. Morris. Nennius — The British History and the Welsh Annals. Chichester, 1980.

J. F. Webb. Lives of the Saints. Harmondsworth, 1965. (recently reissued with the addition of Bede’s Lives of the Abbots as The Age of Bede) Contains the Lives of SS Cuthbert and Wilfrid.

D. Whitelock (ed). English Historical documents Vol 1. (2nd ed.) London, 1979. Contains Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Life of St Wilfrid, and the Ecclesiastical History.

Further Reading

N. K. Chadwick et al. Celt and Saxon. Studies in the Early British Border. Cambridge, 1963.

A. A. M. Duncan. Scotland - The Making of the Kingdom. Edinburgh, 1975.

R. H. Hodgkin. A History of the Anglo-Saxons. (3rd ed.) Oxford, 1952.

P. Hunter-Blair. An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge, 1956.

P. Hunter-Blair. Northumbria in the Days of Bede. London, 1976.

J. Morris. The Age of Arthur. (3 vol. limp ed.) Chichester, 1977.

C. W. C. Oman. England Before the Norman Conquest (9th ed.). London, 1949.

F. M. Stenton. Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.) Oxford, 1971.

F. T. Wainwright. Nechtansmere. In: Antiquity, Vol XXII no.86 (June 1948).

F. T. Wainwright. (ed). The Problem of the Picts. Edinburgh, 1955.