|

Full text of

"The battle of Wavre and Grouchy's retreat;

a study of an obscure part of the Waterloo campaign"

See scans of pages

Index of Illustrations of Costume & Soldiers

THE BATTLE

OF WAVRE &

GROUCHY'S

RETREAT

HYDE KELLY

THE BATTLE OF WAVRE

AND GROUCHY'S RETREAT

A STUDY OF AN OBSCURE PART OF

THE WATERLOO CAMPAIGN

By W. HYDE KELLY, RE.

WITH MAPS AND PLANS

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1905

AUTHOR'S PREFACE

So much has been written on the Waterloo

Campaign that, even in the smallest details,

nothing new can be revealed; but the dazzling

magnitude of the great battle itself has obscured

a part of the campaign which is seldom studied

- the battle against Thielemann, and Grouchy's

skilful retreat from Wavre.

I have chosen this tail-end of the campaign

because little is known about it; because it serves

useful lessons even for to-day; because the opera-

tions leading up to the battle round Wavre are

of great interest; and because a campaign full of

mistakes should be studied as carefully as a cam-

paign free from error. From history we obtain

experience, and experience teaches us how to act

for the future. We learn how great men of old

time fought their battles and managed their

retreats; we see the reasons of their successes and

their failures; and we should endeavour to make

use of our lessons when our own time comes.

vi

PREFACE

Not that Grouchy can be deemed a great soldier;

nor can his part of the 1815 campaign be regarded

as of prime importance in itself; but as showing

the small trifles that mar great plans in their

execution, as showing how little : a thing will some-

times destroy the grandest conceptions, his opera-

tions from 16th June to the end of the month

are well worthy of attention.

I might have employed my time more profit-

ably had I chosen to work upon some more

illustrious name than Grouchy's, or upon some

more modern campaign of greater advantage to

the war student of to-day; but I chose to bring

forward an obscure page in the history of the

most famous campaign, for in that history there

is much that may still be laid to heart.

Great deeds deserve great critics, but, as

Colonel Henderson wrote in his Preface to

" Stonewall Jackson," " if we were to wait for

those who are really qualified to deal with the

achievements of famous captains, we should, as a

rule, remain in ignorance of the lessons of their

lives, for men of the requisite capacity are few in

a generation." Man is not so fortunate that he

can live in every period; and for knowledge he

PREFACE vii

must go backwards to search in history. The

statesman will read of the great quarrels between

Charles I. and his Parliament, not because he

would imitate either the one side or the other, but

because he will desire to mould future action upon

the experience of the past. Napoleon himself

prepared all his ambitious schemes from the pages

of Tacitus, Plutarch and Livy, and the histories

of the deeds of Hannibal, Alexander, and Caesar.

Wellington "made it a rule to study for some

hours every day "; and since these two great men

advocate study of history, who is there who shall

gainsay the advantages of learning ? But the true

method of reading history requires something far

deeper than mere perusal : it must be accompanied

by careful and continuous thought. A true history

will encourage the reader to bury himself in the

very atmosphere of the time, and will bring him

to see with his eyes the comings and goings

of great men, the rights and wrongs of their

deeds, and their impress upon contemporary

people.

This small volume attempts nothing of this

kind: it is a sketch, a mere outline, of a minor

portion of a remarkable campaign. In it I have

viii PREFACE

made no mention of the tactical formations em-

ployed; I have given no details of armaments,

equipments, or means of transport; for these are

now of no value to the soldier - student. The

comments or remarks are to be taken or left, as it

shall please the reader : they are my own views;

possibly they may coincide with the views of others;

in that case they will be interesting.

I may admit that these pages were at first

written for my own use, mere notes taken down

while I read a dozen authorities on the subject. I

afterwards persuaded myself that my studies might

prove of use to those who had little time to search

the volumes in the libraries.

I trust I shall not offend German susceptibilities

by omitting the prefix "von" in the Prussian

names and titles. I only do so to save space.

I have to add my gratitude to the numerous

writers and historians who have told the splendid

story of Waterloo, and from whom I have drawn

my facts.

W. HYDE KELLY.

August 1905.

CONTENTS

I. BRIEF DISCUSSION OF THE EARLIER OPERATIONS UP TO LIGNY . 1

II. THE THIRD PRUSSIAN CORPS AND GROUCHY'S FORCES . . 52

III THE RETREAT OF THIELEMANN'S CORPS FROM SOMBREFFE . 66

IV. GROUCHY'S PURSUIT OF THE PRUSSIANS . . . . 80

V. BLUCHER MARCHES TOWARDS MONT ST JEAN WITH THE FIRST, SECOND, AND FOURTH CORPS . . 100

VI. THIELEMANN'S INSTRUCTIONS AND HIS DISPOSITIONS AT WAVRE . 108

VII. THE BATTLE OF WAVRE . . . . . . . 115

VIII. GROUCHY'S RETREAT . . . . . . . 133

IX. NOTES AND COMMENTS . . . . . . . 153

INDEX ... 165

MAPS

PAGE

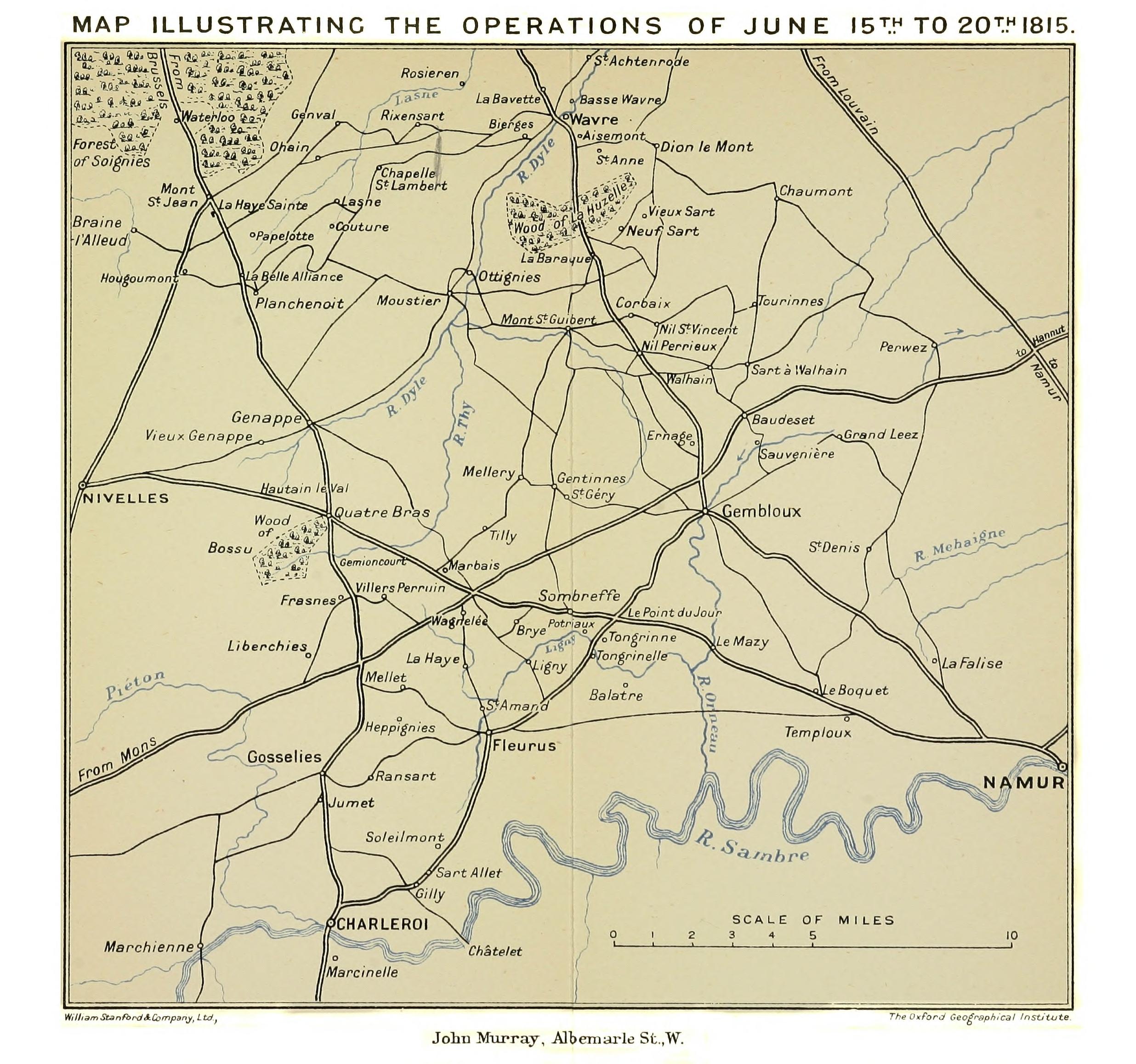

1. ILLUSTRATING THE OPERATIONS OF 15TH-20TH JUNE . . . . . . 1

2. THE BATTLE OF WAVRE: POSITIONS AT DAYBREAK, 19TH JUNE . 115

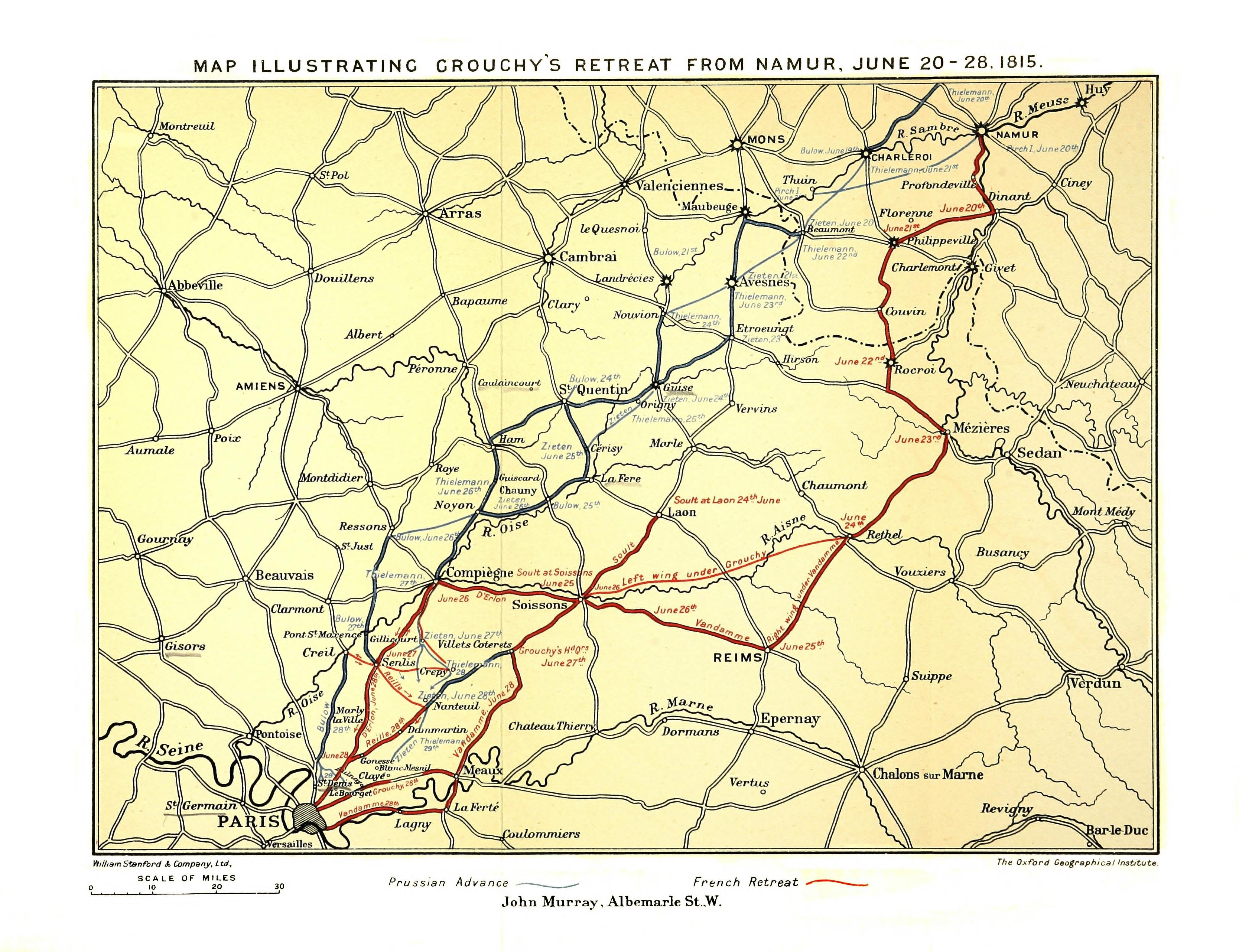

3. ILLUSTRATING GROUCHY'S RETREAT FROM NAMUR . . . . . . . 133

MAP ILLUSTRATING THE OPERATIONS OF JUNE 15TH TO 20TH 1815.

THE BATTLE OF WAVRE AND

GROUCHY'S RETREAT

CHAPTER I

BRIEF DISCUSSION OF THE EARLIER OPERATIONS

UP TO LIGNY

The Allied troops in the Netherlands had begun

to concentrate as early as the 15th of March.

They were cantoned from Treves and Coblentz to

Courtrai. But their commanders were away in

Vienna - both Wellington and Blucher. The

largest number that could be concentrated to

meet a sudden attack on Belgium in April was

80,000 men. Of these, 23,000 were Anglo-

Hanoverian troops, 30,000 were Prussians, 14,000

were Saxons, and the remainder Dutch-Belgians.

The spirit of discipline was almost wholly want-

ing among the Saxons and Dutch-Belgians; the

greater part of them had at one time or another,

served Napoleon, and were not to be trusted,

2 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS

Kleist, commanding the Prussians on the Rhine,

had arranged with the Prince of Orange, who

commanded the troops in the Netherlands, that,

in the event of a French attack, they would retire

together on Tirlemont; thus leaving Brussels

exposed, and giving the enemy a firm footing in

Belgium.

By the 1st of April, Napoleon could have

mustered a force of 50,000 men on the frontier

near Charleroi. He could have marched direct

on Brussels (as the Prince of Orange and Kleist

had agreed to fall back). With Brussels in his

hands, he could have turned and repeated his

favourite strategy by falling upon the allied armies

in turn. Wellington was dreading such an attack.

But the project, although it may have entered

Napoleon's thoughts, was never seriously contem-

plated by him. His army, although rapidly being

raised, organised, and equipped in hundreds of

thousands of men, was not yet in a condition to

enter upon a prolonged campaign. He might

gain a slight temporary success with these 50,000

men; he might be reinforced by another 100,000

in the North; but, meantime, how should he

check the other great invading armies of the

Allies? For their preparations were forging

ahead. Barclay de Tolly was marching with

167,000 Russians in three columns through

GATHERING OF FORCES 3

Germany. Marshal Schwarzenberg, commanding

an Austrian army of 50,000 men, and the

Archduke Ferdinand, at the head of 40,000 men,

were hastening to reach the Rhine. One hundred

and twenty thousand men were being collected

in Lombardy, after Murat's decisive overthrow.

Prince Wrede, commanding a Bavarian army

80,000 strong, was assembling his forces behind

the Upper Rhine. Truly a formidable array!

To strike a premature blow at Belgium with

50,000 men did not therefore commend itself to

Napoleon as a possible opening. By waiting, he

not only increased his army and reserve forces;

he made it appear that the war was being forced

upon him by the threatened invasion of France.

His apparent reluctance to open hostilities would

be a great point in his favour. Then, again, the

plans of the Allies would unfold themselves

presently, and he could strike at will.

While the Allies were planning and re-

planning, discussing and arguing their plans of

campaign, their brilliant adversary was growing

daily stronger. But the position was an intricate

one. A too-hasty invasion of France with ill-

concentrated forces would have brought about

a repetition of the 1814 campaign outside Paris.

There were to be no half-measures with Napoleon

this time.

4 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS

Many plans were put forward by the Allied

generals; and after lengthy discussion, it was

finally decided to adopt a modified scheme

proposed by Schwarzenberg, which was to come

into operation towards the end of July. This

plan provided for the simultaneous invasion of

France by six armies. Wellington, with 92,000

British, Dutch-Belgians, Hanoverians, Nassauers

and Brunswickers, was to cross the frontier

between Beaumont and Maubeuge; Blucher,

with 116,000 Prussians, between Beaumont and

Givet; Barclay de Tolly, with 150,000 Russians,

via. Saarlouis and Saarbruck; and Schwarzenberg,

with 205,000 men - Austrians, Wurtembergers

and Bavarians - by Basle; Frimont, with 50,000

Austrians and Piedmontese, was to advance on

Lyons from Lombardy, while Bianchi, at the

head of 25,000 Austrians, was to make for

Provence. The first four armies were to con-

verge on Paris, by Peronne, Laon, Nancy and

Langres respectively; and the two last were to

create a diversion in the South and support the

Royalists.

This was the final plan of the Allies; but

long before the date fixed for the first moves,

Napoleon was fully acquainted with their designs.

Newspaper reports and secret letters had kept

him informed throughout the preparations. He

THE PLANS OF NAPOLEON 5

tells us that he worked out two alternative plans

of campaign. His first idea was to concentrate

a force of 200,000 men outside Paris, and await

the approach of the Allied armies. He proposed

to gather the First, Second, Third, Fourth,

Fifth and Sixth Corps, the Imperial Guard, and

Grouchy's Cavalry Reserve, round the Capital,

which would be garrisoned by 80,000 regular

troops, mobilised guards and sharpshooters,

strongly entrenched and governed by Davout:

and to concentrate round Lyons Suchet's army of

the Alps, 23,000 men, and Lecourbe's Corps of

the Jura, 8,000 men. All the great fortresses were

strongly garrisoned; and Napoleon intended to

let the Allies advance until they were surrounded

with these powerful garrisons and faced by himself

with 200,000 men. The date fixed by the Allies

for the crossing of the frontier was 1st July. It

would take them three weeks to draw near

Paris. By that time the entrenchments round

the Capital would be completed. But the Allies,

operating on six different lines, would be obliged

to detach large forces to watch Suchet and

Lecourbe, and to mask the great strongholds in

their way. When they had approached Paris,

their great armies would have been thus reduced

to 400,000 men, far from their bases, and faced

by the greatest soldier of modern time. The

6 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS

campaign of 1814 would be repeated, but

Napoleon would have 200,000 men at his back,

and a powerful entrenched camp at Paris. Thus

the Allies would in all probability be crushed

in detail; whether they would recover and over-

whelm Napoleon by sheer weight of numbers

seemed doubtful.

But to allow France to be over-run in the

meantime by the invaders would enrage the

Parisians; and Parisians had always to be

reckoned in any plan of Napoleon's. A more

splendid scheme soon presented itself to him.

He had a great idea of the importance of

winning Brussels : and defensive warfare was un-

worthy of his genius. He resolved to attack

before the Allies should be concentrated. By

the middle of June his available forces on the

Northern frontier would amount to 125,000 men.

" He would enter Belgium : he would beat

in turn, or separately, the English and the

Prussians; then, as soon as new reinforcements

had arrived from the departments, he would effect a

junction with the 23,000 men under Rapp, and

would bear down upon the Austro-Russians." (1)

Here was a plan after his own heart. To

establish himself once more at the head of the

nation he must win a glorious victory for France.

(1) Houssaye.

THE EMPEROR'S INTENTION 7

The minds of Frenchmen were peculiarly suscept-

ible to the inspiriting effects of military glory.

Therefore he would strike at Belgium : he would

separate Blucher from Wellington and beat each

army in turn. And here is revealed the nicety

of his calculations. He must attack and beat

either Wellington or Blucher before they could

join their forces.

" If he directed his line of operations against

Brussels through Ath, and debouched from Lille

or Condé against Wellington's right, he would

merely drive the English army towards the

Prussian army, and two days later he would find

himself face to face with their united forces. If,

on the contrary, he marched against Blucher's

left, through Givet and the valley of the Meuse,

in the same way he would still hasten the union

of the hostile forces by driving the Prussians to

the English. Inspired by one of his finest

strategical conceptions, the Emperor resolved to

break boldly into the very centre of the enemy's

cantonments, at the very point where the English

and Prussians would probably concentrate. The

road from Charleroi to Brussels forming the fine

of contact between the two armies, Napoleon,

passing through Beaumont and Phillippeville,

resolved, by this road, to fall like a thunderbolt

on his foe." (1)

Wellington's troops were scattered in canton-

ments stretching over an arc from Oudenarde to

Quatre-Bras. The Second Corps, under Lord

(1) Houssaye,

8 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS

Hill, formed the extreme right, and occupied

Ghent, Oudenarde, Ath and Leuze. The Corps

was 27,000 strong, of whom scarcely 7,000 were

British troops. The First Corps, under the

Prince of Orange, occupied Mons, Rouelx,

Soignies, Genappe, Seneffe, Frasnes, Braine-le-

Comte, and Enghien. This Corps was 30,000

strong, of whom only 6,300 were British. Its

left rested on Genappe, Quatre-Bras, and Frasnes,

and was in touch with the right of the First

Corps, of the Prussian army, under Zieten, whose

headquarters were at Charleroi. Wellington's

Reserve, 25,500 men, was posted in the neighbour-

hood of Brussels, under the Duke's personal

command. The Cavalry, under Lord Uxbridge,

was comprised in seven brigades, British and

King's German Legion; with one Hanoverian

brigade, five squadrons of Brunswick Cavalry,

and three brigades of Dutch-Belgian Cavalry.

The Brunswickers were stationed near Brussels;

the three Dutch-Belgian brigades were allotted

to the First Corps, and the remainder of the

cavalry were stationed at Ninove, Grammont,

and in the villages scattered along the Dender.

Wellington was expecting an attack by way

of Lille and Courtrai, and always regarded this

direction as Napoleon's best move. For his army

was based on Ostend, Antwerp, and the sea;

DISPOSITIONS OF THE ALLIES 9

hence, had Napoleon attacked by way of Mons,

he would have cut Wellington's communications,

and forced him to evacuate Brussels. On the

other hand, he would have driven the English

army towards the Prussians.

Wellington's dispositions were eminently suited

to rapid concentration on threatened points, while,

at the same time, they were sufficiently scattered

to make the subsistence of the troops possible.

He had selected Oudenarde, Ath, Enghien,

Soignies, Nivelles, and Quatre-Bras as points of

interior concentration; and in this way, by Which-

ever route Napoleon chose to attack, Wellington

could bring his Reserve to the threatened point,

and at the same time bring the remainder of his

forces into concentration, enabling him to throw

at least two-thirds of his whole force in front of

the enemy within twenty-four hours.

Blucher's army, 116,000 strong, was divided

into four Corps. The First Corps, under Zieten,

had its headquarters at Charleroi; and its out-

posts stretched from Bonne Esperance through

Lobbes, Thuin and Gerpinnes to Sossoye. Its

right was in touch with the left of the Prince

of Orange's Corps of Wellington's army. The

Second Corps, under Pirch I., had its headquarters

at Namur. Its Divisions were stationed in

Thorembey les Beguignes, Heron, Huy and

10 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS

Hannut. Its outposts stretched from Sossoye

to Dinant. The Third Corps, under Thielemann,

whose headquarters were at Ciney, had its Divi-

sions stationed at Asserre, Ciney, Dinant and

Huy. Its outposts extended from Dinant

to Rochefort. The Fourth Corps, Bulow's, had

its headquarters at Liege: its Divisions were

stationed at Wareme, Hologne, Liers, Tongres

and Lootz.

Bluchers scheme of concentration enabled

him to collect his four Corps together at their

respective points of assembly at Fleurus, Namur,

Ciney and Liege, within twelve hours. If the

French crossed the Sambre at Charleroi, Blucher

intended to concentrate his army in front of

Sombreffe, on the Namur-Nivelles road, where he

would be within 8 miles of Quatre - Bras,

Wellington's point of concentration under those

circumstances. If Napoleon moved along the

Meuse towards Namur, the First, Second and

Fourth Corps were to concentrate on Namur,

while Thielemann's Corps, the Third, acting from

Ciney, would attack the enemy's right flank. If,

again, Napoleon advanced on Ciney, Zieten,

Pirch I. and Thielemann were to concentrate

their Corps on Ciney, and the Fourth Corps was

to remain at Liege as a Reserve.

These were the dispositions of the Allies; but

THE ALLIES' LINES OF SUPPLY 11

they were not strategically in a sound position.

Wellington's line of supply lay through Ostend

and Antwerp to the sea; Blucher's lay by Liege

and Maestricht to the Rhine. Therefore, in the

event of a disaster to either, or both, their lines of

retreat would carry them further apart. It was

this weakness on which Napoleon based his whole

plan. The Prussian army, being the nearer to

Napoleon, would be the first met with, and there

fore the first to concentrate. By a rapid crossing

of the Sambre at Charleroi, Napoleon would force

the First Corps back on Fleurus, where the

Prussian army was to concentrate, and throw

himself on the point of junction of the Allied

armies when concentrated; namely, the Quatre-

Bras - Sombreffe road. He knew that the

Prussians, by reason of their dispositions, would

be concentrated first, and he therefore hoped, by

possessing himself of the point of junction, to

beat their concentrated army before Wellington,

who, he decided, would be much slower in

assembling his troops, could come up to Quatre-

Bras. It was of vital importance to Napoleon to

beat the Prussian army, entirely and completely,

in its position at Sombreffe, before Wellington

could come to Blucher's assistance. The retreat

of the Prussians on Wavre without such a decisive

defeat, would have upset the whole plan: for

12 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS

Wellington would then have retired and united

with Blucher, either in front of Brussels or behind

it. But, if thoroughly beaten, the Prussians

would retreat on Liege: and only in this way

could Napoleon effectually separate the two armies

and crush them in turn. Such was Napoleon's

argument. In conception, the plan was brilliant;

but its execution was unworthy of him.

Composition of the French Army.

Napoleon's Grand army for the invasion of

Belgium was made up of the First, Second, Third,

Fourth and Sixth Corps dharma; four Corps of

Reserve Cavalry; and the Imperial Guard; a

total of 116,124 men. The First Corps, under

d'Erlon, consisted of the First, Second, Third, and

Fourth Infantry Divisions, and the First Light

Cavalry Division. In the early part of June, the

Corps was stationed at Lille. The Second Corps,

under Reille, consisted of the Fifth, Sixth, Seventh

and Eighth Infantry Divisions, and the Second

Light Cavalry Division. This Corps was

quartered- at Valenciennes. The Third Corps,

Vandamme's, comprised the Ninth, Tenth, and

Eleventh Infantry Divisions, and the Third Light

Cavalry Division, and was stationed at Meziéres.

The Fourth Corps, Gérard's, was composed of the

COMPOSITION OF THE FRENCH ARMY 18

Twelfth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Infantry Divi-

sions, and the Seventh Light Cavalry Division.

The Corps was stationed in Metz, Longwy, and

Thionville. The Sixth Corps, Lobau's, was made

up of the Nineteenth, Twentieth, and Twenty-

first Infantry Divisions; it was stationed at Laon.

Grouchy commanded the four Corps of Reserve

cavalry; these First, Second, Third, and Fourth

Cavalry Corps were commanded by Pajol, Excel-

mans, Kellermann, and Milhaud respectively;

they were mostly stationed between the river

Aisne and the frontier. The Imperial Guard

consisted of twelve regiments of infantry, two

regiments of heavy cavalry, three of light

cavalry, and thirteen batteries of artillery. The

Guard left Paris for Avesnes early in June. To

the First and Second Corps d'Armee were

attached six batteries; to the Third and Fourth,

five batteries; and to the Sixth, four batteries of

artillery.

This army was the best, in point of courage,

warlike spirit, and devotion to himself, that

Napoleon ever led. But the men were without

discipline, and distrusted their leaders. Napoleon's

generals were not the best that had ever served

under him. Ney was a tried veteran, the " bravest

of the brave," but he had just come over to

Napoleon from Louis XVIII. Grouchy had

14 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS

never held an independent command. It is re-

markable that both Ney and Grouchy should

have failed Napoleon in this, his last, campaign;

but neither were fitted to the great trusts com-

mitted to them. Napoleon himself was not the

same man who had beaten back the Allies a

year previously at Montmirail, Montereau, and

Champaubert, but he was still a master of

strategy and the strongest man of France.

The First Movements of the French.

Napoleon began his concentration early in June.

He moved the First Corps from Lille to Avesnes;

the Second from Valenciennes to Maubeuge; the

Third from Meziéres to Chimay; the Fourth from

Thionville to Rocroi; the Sixth from Laon

to Avesnes; and the Guard from Paris to

Avesnes.

The concentration was in full swing, with the

exception of Grouchy's Reserve Cavalry, when

Napoleon left Paris on the night of 11th June.

Grouchy had not received his orders for con-

centration from Soult, the Chief of the Staff,

who had neglected to send them until the 12th.

X" Here was an omission at the outset which might

well have had serious results. But Grouchy lost

no time in setting his Corps on their roads, and

June 15.] THE FRENCH ARMY MOVES 15

by rapid marching he had all his cavalry beyond

Avesnes on the night of the 13th.

On the evening of the 14th Napoleon moved

his headquarters to Beaumont. The First Corps

was on the extreme left, between Maubeuge and

Solre-sur-Sambre; the Second Corps between

Solre-sur-Sambre and Leers; the Third and

Sixth Corps between Beaumont and the Sambre;

the Fourth Corps between Phillippeville and

Florenne; Grouchy's Reserve Cavalry between

Beaumont and Phillippeville; the Imperial Guard

at Beaumont. This concentration was brilliantly

planned, and skilfully executed : worthy of

Napoleon's best days.

The French army crossed the frontier early

in the morning of the 15th of June, in three

columns. The left column (d'Erlon's and Reille's

Corps) crossed by Thuin and Marchienne; the

centre column (Vandamme's, Lobau's Corps,

Imperial Guard, and Grouchy's Reserve Cavalry),

at whose head was the Emperor himself, crossed

by Ham-sur-Heure, Jamioux, and Marcinelle;

the right column, Gérard's Corps, by Florennes

and Gerpinnes. The front was covered by twelve

regiments of cavalry.

The arrangements for relieving the troops of

a fatiguing march by avoiding the crossing of

columns in front of each other, and for the

16 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

communication between each column, were

admirable. The baggage and ammunition wag-

gons, except those of the latter which were

required for immediate use, were kept 9 miles

in rear of the army. The advanced guards of

the different columns communicated constantly

with each other, so that no column should get

ahead of the others. A screen of scouts was

sent out in all directions to obtain every scrap

of information as to the enemy's position, and

report direct to the Emperor. Everything was

to be done to ensure the rapid march of a well-

concentrated army on the point where it was

expected that the Prussians would be met with.

But three of the Corps commanders failed to

carry out their instructions. D'Erlon started

from his camp at half-past four instead of at

three o'clock, as ordered. Vandamme never knew

of the march of the army until Lobau's Corps

pushed on his rear : the orders sent to him from

headquarters had not reached him, owing to an

accident to the officer sent by Soult. And

Gérard, who should have marched at three, did

not reach Florennes until 7 a.m. All this was

carelessness. Soult should have sent such

important orders in duplicate. It is interesting

to observe how these delays affected the subse-

quent movements of the columns on the 15th,

June 15.] THE PRUSSIANS RETIRE 17

But, first of all, the centre column shall be

followed, as being that led by the Emperor

himself. In the advance on Charleroi, Pajol's

cavalry led the way. Zieten's outposts were

everywhere driven in, and when Pajol entered

Charleroi at midday (the 15th) the Prussians

had withdrawn, and taken up a strong position

at Gilly, 2 miles north-east of Charleroi. The

centre column halted to await Vandamme's

arrival; for Grouchy, who did not like the

appearance of the Prussian position, would not

attack until he had Excelman's Cavalry and

Vandamme's Corps with him. Napoleon, im-

patient at the delay, took command in person

at 5 p.m., and pushed home a vigorous attack;

and the Prussians retired at dusk to Fleurus.

Vandamme and the Cavalry bivouacked within

2 miles of the Prussians. The Guard bivou-

acked between Gilly and Charleroi; Lobau's

Corps south of the river, near Charleroi; and

Gérard's Corps on the right, crossing the Sambre

at Chatelet, bivouacked on the road to Fleurus.

Napoleon thus had the Third, Fourth, and Sixth

Corps, the Imperial Guard, and Grouchy's Cavalry

concentrated between Fleurus and Charleroi,

intending to attack the Prussians in strength

next day, either at Fleurus or at Sombreffe.

The Emperor passed the night at Charleroi.

18 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

Had it not been for Vandamme's delay, and

had Grouchy attacked the Prussians at once at

Gilly, the latter could have pushed his enemy

as far as Sombreffe that night, which it was

Napoleon's intention that he should have done.

But Vandamme's slowness prevented Grouchy

from advancing further than Fleurus that evening.

On the Left, matters had not, by nightfall,

progressed as far as Napoleon wished. Reille,

in accordance with his instructions, had marched

with his Corps, the Second, from Leers at 3 a.m.,

and pushed on to Marchienne, everywhere driving

back the enemy's outposts. He was then ordered

to march on Gosselies, where it was reported

that a body of Prussians were in position. He

therefore pushed on his troops along the Charleroi-

Brussels road; and finding Jumet occupied by

a Prussian rearguard, he drove out the enemy,

and reached Gosselies at about 5 p.m. Marshal

Ney now arrived on the scene, and, having just

come from the Emperor, from whom he received

his orders, took over the command of the Left

Wing. Ney pushed on to Frasnes with Piré's

Cavalry and Bachelu's Infantry Division : Girard's

Division was sent to pursue the Prussians, who

had retreated from Gosselies towards Fleurus:

the remaining divisions of Reille's Corps - Jerome's

and Foy's - stayed at Gosselies. Ney drove back

June 15.] NEY'S CAUTION 19

Saxe-Weimar's Brigade from Frasnes at 6.30 p.m.;

the brigade retiring on Quatre-Bras. Lefebvre-

Desnouette's Division of Light Cavalry of the

Guard had arrived with Ney, and was now

moved in support of his infantry at Frasnes.

Thus Ney, at 6.30 p.m., while there were still

nearly three hours of daylight left, had with

him two light cavalry divisions, and one infantry

division, at Frasnes. The distance to Quatre-

Bras was 2 1/2 miles. In less than an hour he

could have reached the cross-roads and attacked

Saxe-Weimar's Brigade. But he merely pushed

his cavalry forward, reconnoitred the position,

and then withdrew his men to Frasnes, himself

returning to Gosselies at about 8.30 p.m.

Now it has been fiercely contested that Ney

received verbal orders from Napoleon to occupy

Quatre-Bras on the night of the 15th. Whether

he did or did not is a point still undecided by

the authorities on the campaign,- but it matters

little, for Napoleon, in his written orders to Ney

on the 16th, expressed his satisfaction with the

progress of the night before, and did not blame

Ney for his failure to occupy the cross-roads. As

a matter of fact, Saxe- Weimar made such a bold

show of resistance to the reconnaissance sent by

Ney, that the latter was entirely deceived as

to his enemy's numbers: he believed that the

20 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

English were in great force there. Had Ney

attacked Quatre-Bras that night, he would have

driven back Saxe- Weimar's Brigade of Nassauers,

the only troops in occupation, and seized the

most important point in the theatre of war. But,

viewing the question from what must have been

Ney's own point of view, he was acting on sound

strategical principles by not pushing ahead too

far. He had only just arrived on the ground,

and was not acquainted with any of his Staff, or

his divisional generals, or even with the strength

of his troops. He believed that a strong English

force held Quatre-Bras, and that, by attacking,

he would be overwhelmed by the whole of

Wellington's army; that Napoleon's Left Wing

would be crushed. He therefore adopted more

cautious methods, and awaited the arrival of

d'Erlon's Corps, and news of the progress of the

Centre and Right Wing.

Prince Bernard of Saxe- Weimar may be

credited with having saved the situation for the

Allies. Had he adhered rigidly to the principles

of strategy, he would have fallen back from

Quatre-Bras; but instead, his fine courage

prompted him to hold on until supports should

arrive, and his boldness triumphed over Ney's

prudence. If Ney had seized Quatre-Bras that

night, and if the succeeding events had taken

June 15.] BLUCHER CONCENTRATES 21

place as they did take place, the battle of

Waterloo would never have been fought, for

Wellington could not have risked a battle

without hope of Prussian assistance. But there

were many little risks and chances which might

have changed the whole result of the campaign!

To return to d'Erlon. By starting an hour

and a half later than he was ordered to do, he

lost most valuable time; and throughout the

day he took no pains to make up for the delay,

although he actually received an order from

Soult, late in the afternoon, to the effect that

he was to join Reille at Gosselies that evening.

Instead of this, by nightfall his leading division,

Durutte's, was at Jumet, l 1/2 miles in rear of

Gosselies, and his Headquarters at Marchienne,

6 miles in rear! Matters had not progressed

at all satisfactorily on the Left Wing.

The 15th of June on the side of the Allies.

Blucher had decided upon a concentration of

his whole army at Sombreffe, in the event of

Napoleon attacking by Charleroi. Therefore, on

the evening of the 14th, he ordered the Second,

Third, and Fourth Corps to concentrate on

Sombreffe, while the First Corps was to make a

stout resistance, and fall back slowly on Fleurus,

22 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

which Zieten was to hold, in order to gain time

for the concentration. These arrangements were

made without any definite agreement between

Wellington and Blucher, as to the Duke's

movements under these circumstances. It was

understood that each should give the other all

the assistance in his power, in the event of a

French attack; but no formal undertaking for

definite action was entered into. Besides, Blucher,

when he ordered his concentration, believed that

Wellington's troops were too scattered to allow

of their concentration within two days. He

could not therefore have expected much actual

support from Wellington. There was also the

possibility that Wellington himself was confronted

with a strong force.

In the concentration of the Prussian Corps,

another defect in the transmission and execution

of orders from Headquarters must be mentioned.

Gneisenau, the chief of Blucher's Staff, sent

instructions to Bulow, commanding the Fourth

Corps, on the 14th, to the effect that he was so

to dispose his Corps that his troops might reach

Hannut in one march. The order was indefinite,

and contained no statement that Napoleon was

about to attack; there was no mention of the

disposition of the other Prussian Corps; no

mention of Blucher's intentions, or of the general

June 15.] NEGLIGENCE AND DELAY 23

situation. This was culpable negligence on the

part of the chief of the Staff It was his

duty under the circumstances to transmit all

such important information to all the Corps

commanders; and because Bulow's Corps was

some distance in rear, is no reason why such a

necessary step should have been omitted. The

result was a serious delay on the part of the

Fourth Corps. At midnight on the 14th, a second

despatch from Gneisenau was sent to Bulow,

ordering a concentration of his Corps on Hannut.

The first despatch reached Bulow at 5 a.m. on the

15th, when he was at Liege. The instructions

contained in it were at once acted upon, and

Bulow sent a report to this effect to Headquarters.

While these instructions were being carried out,

the second despatch arrived towards midday (on

the 15th). Its contents seemed to Bulow to be

impossible to act upon until the next day, for

most of his troops were by this time so far in

their movement that the new order could not

reach them in time to be carried out that night;

also there would be no quarters prepared for those

troops which were still within reach of the new

instructions. Furthermore, this second despatch

was also indefinite. It contained no positive order

that Bulow was to move his headquarters to

Hannut; it merely suggested that Hannut

24 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

appeared suitable. There was no mention of

the commencement of hostilities. Bulow therefore

decided to postpone the execution of this order

until the 16th, and he sent a report to this effect

to Blucher, promising to be in Hannut by noon

next day (16th). The officer sent with this

report reached Namur at 9 p.m., expecting to

find Blucher there, but he discovered that Head-

quarters had been removed to Sombreffe. Mean-

while, a third despatch was sent off at 11 a.m. on

the 15th from Namur, instructing Bulow to move

the Fourth Corps, after a rest at Hannut, on

Gembloux, starting at daybreak on the 16th.

The orderly carrying this message naturally went

to Hannut, where he expected to find Bulow.

At Hannut he found Gneisenau's second despatch

lying unopened, awaiting Bulow's arrival. He

then started off at all speed with both despatches

to Liege, where he arrived at daybreak on the

16th. But by this time Gneisenau's instructions

were impracticable. Thus Bulow, through no

fault of his own, was prevented from reaching

the field of Ligny with his Corps, when his arrival

on the right flank of the French might have had

the same effect that the arrival of the Prussian

army had at the great battle two days later.

While the concentration of the Second and

Third Corps was rapidly progressing behind him,

June 15] THE FIGHTING COMMENCES 25

Zieten was occupied with his retreat on Fleurus.

At half-past three in the morning of the 15th,

the Prussian picquets in front of Lobbes, a village

on the Sambre, were driven in by the advanced

guard of the French Left Column (this was the

head of Reille's Corps advancing). An hour later,

the French opened with artillery on Maladrie,

a hamlet about a mile in front of Thuin. It was

this cannonade which was heard by the troops of

Steinmetz's Division in Fontaine l'Evêque, and

even Zieten at Charleroi heard it. He therefore

lost no time in sending reports to both Blucher

and Wellington that fighting had actually

commenced. His report to Wellington gave

the Duke definite news that an attack on

Charleroi was imminent, but it did not induce

him to alter his plans in any way. For Welling-

ton was still apprehensive of an attack by way

of Mons, and he judged that his army was in the

best position to meet such an attack. He was

unwilling to engage himself in a move eastwards

while there was a chance of the French attacking

from the westwards. With such a belief, it is

clear that Wellington, by concentrating pre-

maturely at Quatre-Bras, which it was his inten-

tion to do if Napoleon's attack should eventually

be by the Charleroi - Brussels road, would merely

carry out the very move which his enemy would

26 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

wish. Therefore he awaited more definite news

of the French attack on Zieten.

But Zieten's report to Blucher made the

Marshal more than ever assured of the wisdom

of concentrating at Sombreffe.

The retreat of Zieten's Corps was very ably

carried out. The Prussians at Maladrie, after

maintaining a stubborn resistance, were finally

overpowered, but they retreated in good order on

Thuin. Here they joined a battalion of West-

phalian Landwehr, and resistance was made until

7 a.m., when, after suffering very heavy losses, the

Prussians fell back to Montigny . Here, again,

they joined two squadrons of Dragoons, who

covered the rest of their retreat to Marchienne.

But the French cavalry, under Pajol, pushed on

so vigorously, and the small retreating column

suffered such severe losses, that, upon arrival at

Marchienne, a mere skeleton was left. By this

time also the outposts at Lobbes had effected

their retreat on Marchienne. General Steinmetz,

commanding the First Division of Zieten's Corps,

was now fully aware of the French attack. He

therefore sent a staff officer to warn Van Merlen,

who commanded the Dutch-Belgian outposts at

St. Symphorien between Binche and Mons, and

to inform him that he was falling back with his

Division upon Charleroi.

June 15.] ZIETEN'S RETREAT 27

The manner in which the outposts fell back,

and the readiness with which reports as to the

enemy's movements and those of the several

Prussian picquets and supports were passed from

one part of the retreating Division to the other,

and from the right of Zieten's corps to the left

of Wellington's army, are worthy of the closest

attention. The Prussian commanders thoroughly

understood the value of rapid and accurate

information, distributed to all parts of their

commands. The long Napoleonic wars had taught

them something of their profession.

Zieten's management of his retreat marks him

as a very capable soldier. Towards 8 a.m. he

satisfied himself that the whole French army was

making for Charleroi. He therefore sent out the

following orders for retreat: the First Division

(Steinmetz's) to retire by Courcelles to Gosselies,

and take up a position behind the village; the

Second, Division to gain time for the retreat of

the First by defending the bridges over the

Sambre at Chatelet, Charleroi, and Marchienne;

it was then to fall back behind Gilly. The Third

and Fourth Divisions, with the cavalry and

artillery reserves, were to take up position at

Fleurus.

Meanwhile, Napoleon was pushing rapidly on

Charleroi with the Imperial Guard and Pajol's

28 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

Cavalry Corps. The Prussian detachment holding

the bridge connecting Marcinelle and Charleroi

made a stout defence, but was soon overpowered,

and by noon the French had obtained possession

of the town. The Third and Fourth Divisions

of Zieten's Corps were by this time well on the

road to Fleurus, but Steinmetz's Division was in

great jeopardy. For the French were already

masters of the Sambre, even below Charleroi,

and the First Division was in danger of being

cut off from its retreat on Gosselies. Accordingly

Zieten, with great resolution, detached three

battalions of infantry from the Third Division,

and sent them to Colonel Lutzow, who was

holding Gosselies with a regiment of Lancers

from Roder's Reserve Cavalry. Lutzow placed

one battalion in Gosselies, and took up a position

in reserve with the remainder. As soon as the

French had taken Charleroi, Napoleon ordered

Pajol to send a brigade of Light Cavalry towards

Gosselies, and to take the remainder of his Corps

towards Gilly. The Brigade actually reached

Jumet ahead of Steinmetz's Division, which had

not yet crossed a small stream called the Piéton,

which ran between Fontaine l'Evêque and

Gosselies. But Colonel Lutzow went out with

his regiment of Lancers from Gosselies, met the

French Hussars, and drove them back with loss,

June 15.] STEINMETZ AVOIDS NEY 29

enabling Steinmetz to reach the village in

safety.

In the meantime reinforcements, consisting of

the advanced guard of Reille's Corps, were being

pushed along the Gosselies road, with a view to

cutting off Steinmetz's retreat, and separating

Zieten's Corps from Wellington's army. This

move of the French was very skilful, but Stein-

metz, perceiving that his position was one of

great danger, made a feint against the French

left flank, and, covering his retreat with a regiment

of Lancers and one of Hussars, withdrew to

Heppignies, a village half-way between Gosselies

and Fleurus. Had Steinmetz been caught and

surrounded at Gosselies, Blucher would have been

weaker by one Division in the great struggle at

Ligny next day; and he could ill afford to reduce

his numbers.

Ney, who had taken over the command of

the French Left Wing, and who was at this

time pushing on with Piré's Cavalry and Bachelu's

Infantry to Frasnes, sent Girard's Division of

Reille's Corps to pursue Steinmetz. Girard

occupied Ransart, and made an attack upon

Heppignies, but the Prussians drove him back,

and retired in good order to Fleurus, thus rejoin-

ing the main body of their Corps, and effecting

their retreat in a very skilful manner.

30 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

In the Prussian centre, meanwhile, Pirch II.'s

Second Division, which had been ordered to gain

time for the retreat of the First, retired to Gilly,

on the road to Fleurus, when the French entered

Charleroi. At Gilly the Prussians took up a

strong position and prepared to delay the French

advance as much as possible. Pirch's line of

defence stretched from Soleilmont on his right,

to Chatelineau on his left; and a small stream

ran in his front at the foot of the ridge on

which his position stood. His left flank was

further strengthened by a detachment holding

the bridge over the Sambre at Chatelet. Cavalry

patrols watched the valley of the Sambre for the

approach of Gérard's Corps, which was already

marching on Chatelet. Had Gérard marched

earlier from Phillippeville, he would have pre-

vented, by his occupation of Chatelet earlier in

the day, Pirch's stand at Gilly.

Grouchy had orders to take Vandamme's Corps

and Excelmans' Cavalry, and pursue the Prussians

along the Charleroi- Fleurus road; but he was

deceived as to the strength of the enemy at

Gilly. Fearing to attack without further rein-

forcements, he rode back to Napoleon for instruc-

tions. This was at about 5 p.m. Napoleon,

fretting at the delay, which he regarded as

needless, himself rode out with four squadrons

June 15] DETAILS OF THE FIGHTING 31

of Cavalry of the Guard, and reconnoitred Pirch's

position. He soon satisfied himself as to Pirch's

real strength, and gave Grouchy orders to attack

at once. Accordingly, at 6 p.m., artillery fire

opened on the Prussians from two batteries;

three infantry columns from Vandamme's Corps

were ordered to assault in front, and two cavalry

brigades to menace the Prussian flanks. Pirch

was preparing to reply to the French artillery

fire, when he received orders from Zieten to

retire on Fleurus via Lambusart. As soon as

he began to withdraw his battalions, the French

cavalry, under Letort, made a vigorous attack.

The Prussian infantry resisted stoutly, and a

regiment of dragoons, with great boldness, charged

the French squadrons with such effect that they

were for the moment checked, and the Prussians

were able to gain the cover of the wood of

Fleurus. A battalion of the Sixth Regiment of

the Line, by forming square repeatedly, bravely

kept the enemy's cavalry at a distance, and

gained very valuable time for the retreat of the

rest of Pirch's Division. In front of Lambusart,

where Pirch joined some battalions of the Third

Division and Roder's Reserve Cavalry, a fresh

position was taken up, and a regiment of

Brandenburg Dragoons, sent by Zieten to support

Pirch II., did excellent service by charging the

32 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 16.

French horsemen and checking their pursuit.

Towards eight o'clock three batteries of French

Horse Artillery, which accompanied the cavalry,

opened fire on Lambusart; but night was coming

on, and the attack died out very shortly after-

wards. Pirch II. then withdrew to Fleurus,

where he joined the remainder of Zieten's

Divisions, and the whole Corps retreated to

Ligny. Steinmetz had reached Fleurus from

Heppignies at about 10 p.m.

Zieten's retreat in the face of almost the whole

French army is worthy of close attention. His

men had been marching and fighting from three

o'clock in the morning until ten o'clock at night,

and had engaged the enemy in one or two very

sharp conflicts. The skilful manner in which

each Division was withdrawn without getting too

closely engaged with the enemy, and in which

the Divisions supported each other, is illustrative

of the best methods of war. That he was able

to concentrate his Corps at Fleurus with a loss of

only 1,200 men, after having checked the rapid

onset of the French, speaks very highly for Zieten's

skill in generalship. The campaign of Waterloo

still affords useful lessons and examples to modern

students.

The Prussian Second Corps, under Pirch I.,

reached Sombreffe by ten o'clock at night; the

June 15.] ON WELLINGTON'S SIDE 33

Third Corps passed the night at Namur; while

the Fourth Corps was still near Liege.

On Wellington's side, Van Merlen, command-

ing the outposts between Mons and Binche,

received the report from General Steinmetz at

8 a.m., to the effect that the French had attacked

and driven in his outposts, and that he was falling

back on Charleroi with his Division. Early in the

morning the troops of Perponcher's Dutch-

Belgian Division, which was stationed at Hautain-

le-Val, Frasnes, and Villers Perruin, heard firing

from the direction of Charleroi. In the afternoon,

definite news reached them of the enemy's attack

on Charleroi, and Perponcher at once assembled

his First Brigade (Bylandt's) at Nivelles. A

picquet of the Second Nassau battalion was posted

in front of Frasnes to give warning of the French

advance. In the meantime, Prince Bernard of

Saxe Weimar, with his Brigade of Nassau troops,

belonging to Perponcher's Division, on his own

initiative moved forward from Genappe to Frasnes,

reporting his action to the headquarters of his

division at Hautain-le-Val; and Perponcher

approved. When Ney advanced on Frasnes in

the evening, with Piré's cavalry and Bachelu's

infantry, Saxe Weimar, after making a deter-

mined show of resistance, skilfully withdrew

behind Quatre-Bras, and Ney, as before-men-

34 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15.

tioned, was quite deceived as to his actual

strength, and forebore to attack that night

Zieten's report to Wellington, sent off from

Charleroi at 5 a.m., reached the Duke's head-

quarters at Brussels at 9 a.m. Wellington did

not consider the news sufficiently definite to cause

him to make any immediate alteration in his

dispositions. But at three o'clock in the after-

noon, the Prince of Orange, coming from the

outposts near Mons, where he had seen Van

Merlen, and obtained information of the attack

on the Prussians and of their retreat, reported his

intelligence to the Duke. Wellington was now

satisfied of the true direction of the French attack,

but he sent orders to General Dornberg at Mons

to report at once any movement of the French in

that direction. He then ordered his troops to

concentrate at their respective headquarters. On

the left, Perponcher's and Chassé's Divisions were

to assemble at Nivelles; the Third British

Division (Alten's) was to concentrate at Braine-

le-Comte and march on Nivelles in the night;

the First British Division (Cooke's) was to

assemble at Enghien. In the centre, Clinton's

Division (the Second British) was to collect at

Ath, and Colville's (the Fourth British) at Gram-

mont. On the right, Steedman's Division and

Anthing's Brigade of Dutch-Belgians were to

June 15.] THE ALLIES DRAW CLOSER 35

march on Sotteghem. Uxbridge's cavalry was

to assemble at Ninove, except Dornberg's Brigade,

which was to march on Vilvorde; (still Welling-

ton had apprehensions for his right). The Reserve

was kept in readiness in and around Brussels;

with orders to be prepared to march at once.

Late that night (the 15th), towards ten o'clock,

news of Ney's attack at Frasnes was received by

the Prince of Orange at Braine-le-Comte. The

latter forwarded the report to Wellington, adding

that Saxe Weimar had fallen back to Quatre-Bras,

and that the French advance had been checked

there. A despatch from Blucher at Namur also

reached Wellington about this time, and the Duke

decided to march his troops more to their left - i.e.

towards the Prussians. He therefore issued a

second batch of orders that night, directing

Cooke's Division from Enghien to Braine-le-

Comte; Clinton's and Colville's Divisions from

Ath and Grammont to Enghien; and the cavalry

from Ninove to Enghien. The other dispositions

were to remain as they were.

At the close of the 15th, Napoleon's position

promised success for his efforts next day. Blucher

had only Zieten's Corps concentrated at Ligny;

Pirch's Corps was still some miles back.

Wellington's army was still far from Quatre-

Bras. Surely, if Napoleon advanced to the

36 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15-16.

attack of the Prussians at daybreak on the 16th,

he must, with his overwhelming forces, crush

half of Blucher's army and force the remainder

to fall back on Liege! And Ney, if he attacked

with Reille's and d'Erlon's Corps (for the latter

might have pushed on during the night) - or

even with Reille's Corps and Piré's Cavalry -

could have driven back the English force at

Quatre-Bras, which, by daybreak on the 16th,

had only been reinforced by the remainder of

Perponcher's Dutch-Belgian Division? Ney had

ridden to Charleroi in the night, and had had

an interview with Napoleon. He must, therefore,

have known the state of affairs in the centre

and on the right; he must have told Napoleon

how matters stood on his wing. Why did not

Napoleon order him to attack Quatre-Bras at

daybreak on the 16th? There is no satisfactory

answer. It is inconceivable that Napoleon, than

whom no general has ever been bolder and more

decisive in his moves or quicker to take action

at critical moments, should have neglected to

spend the night of the 15th in bringing up the

troops in rear - Lobau's Corps, d'Erlon's Corps,

Gérard's Corps. What if the columns had

straggled out and become doubled in length?

Had Napoleon's troops never made a greater

effort in his earlier campaigns? There is no

JUNE 16.] NAPOLEON'S MISTAKE 37

doubt existing that Napoleon, great warrior as

he was, let his opportunity slip on the night of

the 15th. His advanced troops were within

2 miles of Ligny, and 3 of the Quatre-Bras-

Sombreffe road. Was not this the very point

he had aimed at so carefully in his plan of

campaign? He was already almost master of

the line of junction of Wellington's and Blucher's

armies. He had, in fact, almost, but not quite,

attained the main objective of his scheme. It

was within his grasp on the night of the 15th.

How could Wellington prevent Ney from captur-

ing Quatre-Bras at daybreak on the 16th? And

how could Blucher save Ligny and Sombreffe, if

Napoleon chose to bring up his two Corps from

Charleroi and Chatelet, and attack at dawn

with these overwhelming numbers? Both these

attacks would have called for great efforts from

the French troops, who had been marching and

fighting since 3 a.m. on the 15th; but the attacks

would have been finished in three or four hours,

and then Napoleon could have thought of giving

rest to his tired infantry, while his cavalry

pursued the Prussians back towards Liege. A

day spent in resting and in concentrating, and

Napoleon could have turned to deal with

Wellington. The Napoleon of Jena and Auster-

litz would have won the campaign on the 15th.

38 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 15-16.

But the delays of the 15th were insignificant

in comparison with those of the 16th. And

there were not only delays on the 16th, but

very serious mistakes - although of a kind without

which no war has ever been waged. It is not

our intention to criticise these mistakes so much

as to discuss their effects on the course of the

campaign, and to illustrate their grievous results.

Movements on the 16th.

Ney, on his return to Gosselies from his inter-

view with Napoleon, ordered Reille to move

Jerome's and Foy's Divisions, with his five

batteries of artillery, to Frasnes, whither he

himself went. Ney's misgivings as to the wisdom

of attacking Quatre-Bras were not unfounded.

He feared a movement against his right flank

by a strong force of Prussians whom he believed

to be between Quatre-Bras and Ligny. He was

anxious for his left flank, in case some of

Wellington's troops were moving against him

from the direction of Nivelles. He was ignorant

of the real strength in front of him at Quatre-

Bras. He had no staff officers whom he could

send out to gather information on these points.

He was unwilling to risk damaging Napoleon's

plans by inviting defeat while so far in advance

June 16] QUATRE-BRAS 39

of the centre column. He therefore waited for

d'Erlon's Corps and Kellermann's Corps of heavy

cavalry, which Napoleon had promised to send

him. He despatched orders to d'Erlon to bring

up the First Corps with the utmost speed to

Frasnes.

In the meantime, Wellington's troops were

fast moving on Nivelles and Quatre-Bras. Lord

Uxbridge's Cavalry and Clinton's Division were

ordered, to move on Braine-le-Comte, and Steed-

man's Division with Anthing's Brigade from

Sotteghem to Enghien at daybreak. Picton's

Division started from Brussels for Quatre-Bras

at 2 a.m. The Duke of Brunswick, with 5,000

Brunswick infantry, left at 3 a.m. At 3 a.m.

also Perponcher reached Quatre-Bras with his

First Brigade of Dutch-Belgians, under Bylandt.

The Prince of Orange arrived at Quatre-Bras at

6 a.m., reconnoitred Ney's position, and pushed

Perponcher's troops further forward. He gave

orders that as great a show of strength as possible

was to be made, but a close or premature engage-

ment with the enemy was to be avoided. Thus

at 7 a.m. the Prince had 9 battalions of Dutch-

Belgian troops, and 16 guns, holding Quatre-

Bras; Ney opposite, with Piré's Division of

Lancers, Bachelu's Division of Infantry, and

Lefebvre-Desnouette's Cavalry of the Guard, in

40 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 16.

all 9,700 men, and the remainder of Reille's Corps

in support at Frasnes!

Wellington himself arrived at Quatre-Bras at

11 a.m., inspected the position, saw that the

French were not preparing an immediate attack,

and complimented the Prince of Orange on his

dispositions. He then rode off to the mill of

Bussy, where he met Blucher. It is not necessary

to go into the details of this interview. Suffice

it to say that Wellington agreed with Blucher

that he would come to the latter's assistance at

Ligny, if he was not himself attacked.

At 11 a.m. Ney received from Napoleon a

letter giving him detailed instructions as to the

movements of the French army. The Emperor

told Ney that he intended attacking the Prussians

at Ligny, driving them back on Gembloux.

Ney was then to march on Brussels, and Napoleon,

marching by the Sombreffe-Quatre-Bras road

with his Imperial Guard, would support him.

Thus, according to the letter, Ney's movements

were to wait upon Napoleon's. This interpreta-

tion was some cause of Ney's delays on the 16th.

Soon after the receipt of Napoleon's letter, Ney

received an order from Soult, chief of the Staff,

directing him to move the First and Second Corps,

and Kellermann's Cavalry, on Quatre-Bras, drive

back the enemy, and reconnoitre as far as he could

June 16] GIRARD'S REPORT 41

towards Nivelles and Brussels; also to push a

division to Genappe, and another towards Marbais,

so as to open communication with Napoleon's left

between Sombreffe and Quatre-Bras. Napoleon's

intention was to reach Brussels by daybreak on

the 17th, having defeated the Prussians, and Ney

having defeated the English!

In accordance with this order, Ney sent

instructions to Reille and d'Erlon. These were

to the following effect: - The First, Second, and

Third Divisions of d'Erlon's Corps were to

move to Frasnes; the Fourth Division of that

Corps, with Piré's Cavalry, was to move to

Marbais; Kellermann's Cavalry Corps to Frasnes

and Liberchies.

Just at this time, a message from Reille

reached Ney, stating that Girard (not Gérard,

who commanded the Fourth Corps) had sent in

a report that strong columns of Prussians were

moving along the Namur-Nivelles road, with heavy

masses behind them. (These were Pirch II's

troops deploying at St Amand and Ligny.)

Reille had seen Napoleon's letter to Ney, and

read its contents, but he wrote to Ney that he

would wait the latter's instructions, while he

prepared his troops for instant march. Another

order from Napoleon reached Ney at this moment.

It stated that the Marshal was to unite the First

42 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 16.

and Second Corps with Kellermann's Cavalry,

and drive the enemy from Quatre-Bras, thus

distinctly emphasising the previous order. The

Emperor, who thought that Ney would then

have an ample force to crush any troops which

could be in front of him, stated that Grouchy was

about to move on Sombreffe.

Girard's report as to the Prussian columns on

the Namur road made Ney doubly anxious for

his position. He therefore again sent urgent

orders to Reille and d'Erlon to hasten up. At

2 p.m., in the belief that d'Erlon must be close

behind, he moved to the attack of the Anglo-

Dutch position with three infantry divisions

(Bachelu's, Foy's and Jerome's, of Reille's Corps)

and Piré's Division of Light Cavalry, with

5 batteries - a strength of 18,000 men and 40

guns. Opposed to him were the 7,000 infantry

and 16 guns of the Prince of Orange.

It is not proposed to give an account of the

battle of Quatre-Bras. It has been shown what an

opportunity Ney had lost by not attacking earlier,

and what his reasons were for not doing so.

Picton's Division and the Duke of Brunswick's

Division arrived early in the afternoon, and

Wellington took over the command. These rein-

forcements, to which were added towards the close

of the day, Alten's Division, Cooke's Division,

June 16.] RESULTS OF QUATRE-BRAS 43

two more Brunswick battalions and a battery of

Brunswick artillery, gave Wellington a superiority

in numbers over Ney, who was only reinforced by

Kellermann's Cavalry Corps during the battle.

D'Erlon's Corps had, in the meantime, been

wandering between Ligny and Frasnes.

In its results the battle of Quatre-Bras was of

great importance to both sides. Although Ney

had not obtained possession of Quatre-Bras, and

had not defeated Wellington's troops, nor driven

them back on Brussels, yet he had effectually

prevented Wellington joining with Blucher's right.

He had not been guilty of disobeying orders, and

he himself did not feel confident of victory when

he attacked on the afternoon of the 16th. On the

other hand, Wellington had, by his masterly

defence, completely frustrated Ney's object. He

was now in full possession of Quatre-Bras; he had

gained a brilliant victory, and his divisions were

still coming up from behind, Should he receive

news of a Prussian victory at Ligny, he was

prepared to attack Ney next morning, and, if

successful, to join Blucher's right wing and fall

upon Napoleon's left. If the Prussians were

defeated at Ligny, he was ready to fall back and

take up a position where Blucher could join him,

and together they would attack Napoleon's com-

bined forces.

44 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 16.

To turn to events upon the Prussian side,

Blucher's decision to stand at Ligny was

determined by several strategical considerations.

Firstly, the position he chose communicated with

Wellington's left by 6 miles of very good road,

along which co-operation on either hand could be

easily effected. Secondly, he guarded the com-

munications with Aix-la-Chapelle and the

Prussian States. Thirdly, if the Allies should

be defeated both at Quatre-Bras and at Ligny,

then two parallel lines of retreat, the one upon

Mont St Jean towards Brussels, and the other

upon Wavre towards Louvain, were available,

which would render possible a junction near the

forest of Soignies. Fourthly, if Napoleon had

advanced against Wellington by way of Mons,

the Prussians, by concentrating at Sombreffe,

could have marched to the Duke's assistance,

leaving Zieten to watch Charleroi and the

neighbourhood. Fifthly, if Napoleon had

advanced on Namur, the Third Corps (Thiele-

mann's) could have retreated as did Zieten's, and

allowed time and protection for the First, Second,

and possibly the Fourth Corps, while Wellington

moved to join the Prussian right.

The situation of the Allied armies was not

exactly that of the Austrians and Sardinians in

Italy in 1796-97; there was the possibility of

June 16.] QUATRE-BRAS-SOMBREFFE ROAD 45

striking at their point of junction and of beating

each army separately, but the short and excellent

line of communication between the points of

concentration of Wellington's and Blucher's

armies, namely, the Quatre - Bras - Sombreffe

road, afforded each army such easy and rapid

means of effecting a junction, although, in fact,

it was not actually used as a means of co-

operation, that there was a " moral " influence

in it which went a long way towards defeating

Napoleon's object. This may sound somewhat

exaggerated; but what was it that made Ney

uneasy for his own right flank on the 15th- 16th,

before he attacked? The report sent by Girard

that Prussian columns were on that road. What

was Napoleon's fear during the battle of Ligny?

That Wellington would send a force from Quatre-

Bras to join Blucher's right, along this road.

What was the chief advantage in Wellington's

position at Quatre-Bras ? This road again, which

afforded a means of joining the Prussians at

Ligny, had the occasion arisen. And in what

way was this road of use to Blucher at Sombreffe

He could co-operate with Wellington if Napoleon

had attacked via Mons.

Blucher had decided to fight at Ligny, even

though he had little hope of the arrival of Bulow's

Corps in time to join the battle. For he believed

46 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 16.

that Napoleon's forces were not superior to his

own in numbers; he had selected the position

previously, and had had it surveyed carefully;

he hoped that he would be able to hold his own

either until Bulow arrived, or until hight put

an end to the fight. In the event of the Fourth

Corps reaching the field in time to take part,

the extra weight in numbers would decide in

Blucher's favour, or else the Corps would attack

Napoleon's right flank at a time when his troops

would be most fatigued. Or again, if night came

on, sufficient time would have been gained for

Bulow's arrival to be made certain before day-

break next day, when a successful attack on the

French might confidently be expected. In both

cases, any pressure on Wellington would be

relieved, so that the Anglo-Dutch Army might

combine with Blucher to overwhelm the whole

of Napoleon's forces. Thus Blucher reasoned.

To refuse a battle would have meant a retreat

along his communications with the Rhine, and

Blucher was most unwilling to abandon his

chances of joining with Wellington.

The battle itself will not be described; but

d'Erlon's wanderings towards the field and away

from it again, and the influence of these aimless

manoeuvres on the struggle, may be discussed here.

At eight o'clock that morning (the 16th),

June 16.] LIGNY 47

Napoleon had sent orders to Ney to detach one

Division of his force to Marbais, so as to support

the Emperor and attack in rear the Prussian right,

while the battle of Ligny was at its height. At

2 p.m., he had ordered Ney to attack and defeat

whatever force might be in front of him (he had

ascertained that Ney must be greatly superior

in numbers to the force that opposed him), and

then to move along the Namur road and fall on

Bluchers rear. At 3.15 p.m. this order was

reiterated, and in the most emphatic manner was

Ney ordered to bring the whole of his forces to

bear on the Prussian right and rear. When,

therefore, at 5.30 p.m., Napoleon was preparing

his greatest blow at Blucher and getting in

readiness his Reserves to crush the Prussian

Centre at Ligny, the news that a strong column

of infantry, cavalry, and artillery was making for

Fleurus on the French left arrived, and it might

have been guessed that this was a part of Ney's

forces, acting in accordance with the instructions

sent to the Marshal, but sadly in the wrong

direction. Instead of moving against the Prussian

right, this column was making for the left rear

of the French. Vandamme, who forwarded the

report to the Emperor, suspended his movements,

and Girard fell back with his Division, until the

uncertainty should be cleared up. For it was

48 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 16.

possible, perhaps, that Wellington had overcome

I Ney and was marching to assist Blucher; Ney

had sent no tidings during the day. Napoleon,

at first, believed that the force was the Division

despatched by Ney in accordance with the eight

o'clock order; but he reflected that the numbers

were too great for a Division, and that Ney had

been ordered to send the force by Marbais. Then,

when Vandamme's suspicions were supported by

a second report, he became extremely uneasy;

he suspended his projected attack on the Prussian

centre : and sent off an officer of his staff to

ascertain the truth. At 7 p.m., nearly two hours

after the first appearance of the strange column,

the staff-officer returned, with the tidings that

d'Erlon's whole Corps was at hand, and was

marching to join Napoleon's left. On the. receipt

of this news, the advance of the Imperial Guard

was renewed, and Girard's Division resumed its

former position in fine.

How d'Erlon had arrived in this position

may be explained with little difficulty. When

Napoleon's aide de - camp, Laurent, reached

Gosselies with the morning order, he found

that the First Corps was already marching

towards Quatre-Bras, and that d'Erlon himself

had gone forward to Frasnes. Laurent hastened

to find him, and on overtaking the columns of

June 16.] D'ERLON'S ERROR 49

the First Corps on his way, he took upon

himself the responsibility of changing their

direction towards St Amand. D'Erlon, on

learning what had been done, rode off at once

to join his Corps, sending word to Ney to

inform him what had happened. The road from

Frasnes towards St Amand lay through Villers-

Perruin, and it was this direction which brought

the column into such an unexpected position

towards the French rear. On reaching Villers-

Perruin, however, d'Erlon sent out a Light

Cavalry Brigade to his left, as a precautionary

measure. This Brigade encountered a Prussian

Brigade of Hussars and Lancers under Marwitz,

who withdrew slowly and in good order. Girard's

Division, perceiving the Prussians retire, became

reassured, and moved forward to its original

position. But now, d'Erlon received from Ney

a most urgent and peremptory order to rejoin

him at once. D'Erlon, who acted under Ney's

immediate orders, decided that it was his duty

to obey those orders; and since he had received f

no definite instructions from the Emperor as to

how he should act when he had brought his

Corps on the field, he turned about and left the

ground. Thus he was too late in his return to

be of use to Ney at Quatre-Bras, and the

eccentric direction given to his columns, although

50 THE EARLIER OPERATIONS [June 16.

the natural outcome of his previous dispositions,

served to postpone Napoleon's great attack with

his Guard for two hours; and, when the addition

of 20,000 men might have entirely overwhelmed

the Prussians, he calmly withdrew his men.

D'Erlon's error was his inaction when he

arrived on the field, and not so much his diver-

sion from Ney's orders. He must have known

that he could not return to Quatre-Bras in time

to be of any service; but that by following up

Marwitz, and falling on the rear of the Prussian

right wing, he would be most likely to render

the very greatest assistance to Napoleon. How

he could have failed to realise the importance

of his presence at such a juncture surpasses

all imagination. The very fact that Marwitz's

Brigade had been able to present some show of

compactness before Jacquinot's Cavalry might

have proved to him that there was still a stout

resistance to be expected on the part of the

Prussians. Again, we think Napoleon should

have sent instructions as to how d'Erlon should

act, by his aide-de-camp, in the event of the

strange column being French. Had d'Erlon

remained on the left wing to assist Ney, Quatre-

Bras might have been won by the French. Had

he realised the uselessness of a return march to

Ney when he was yet at hand to help Napoleon,