Find the perfect fit with Amazon Prime. Try Before You Buy.

Try Amazon Fresh

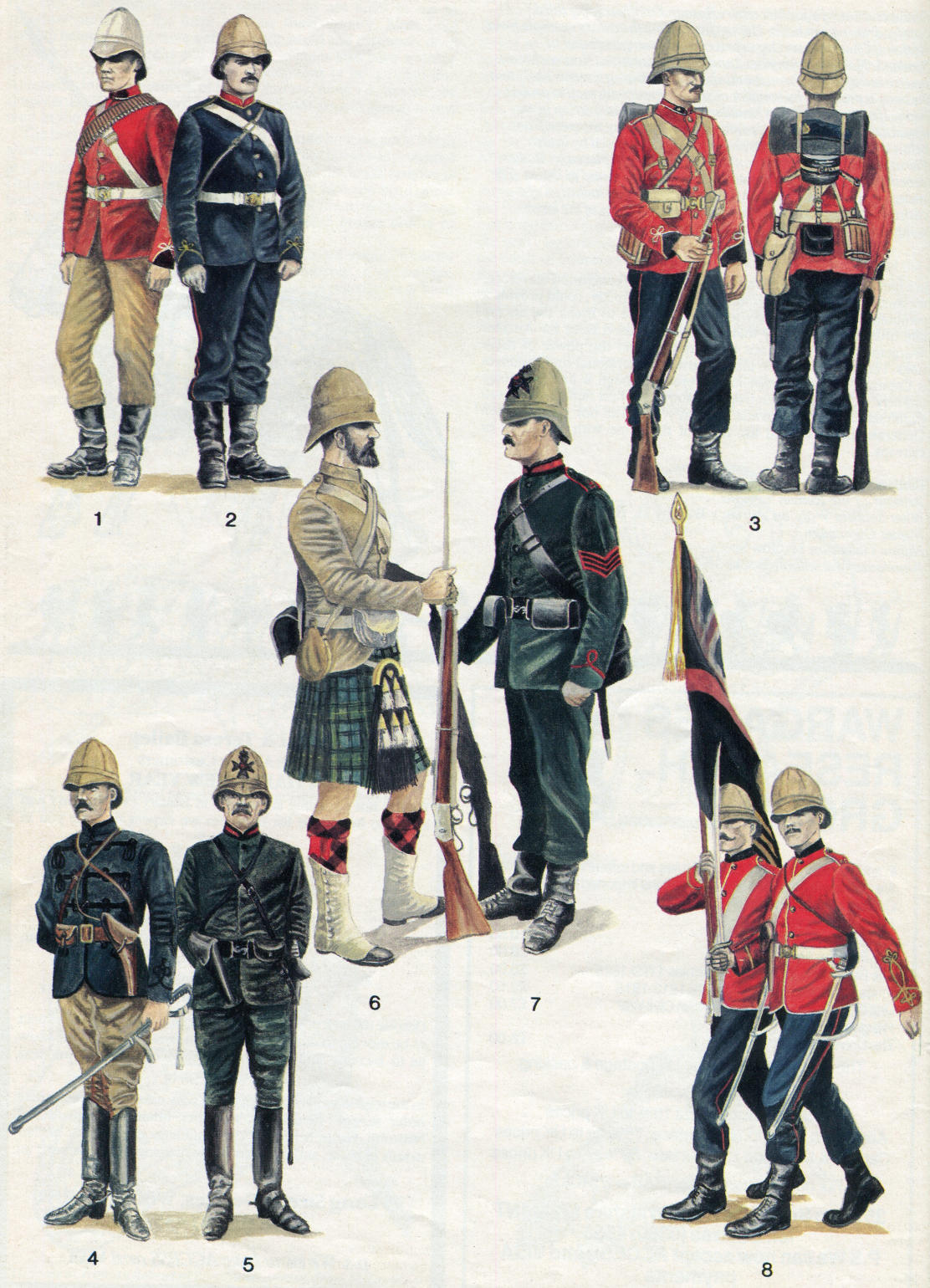

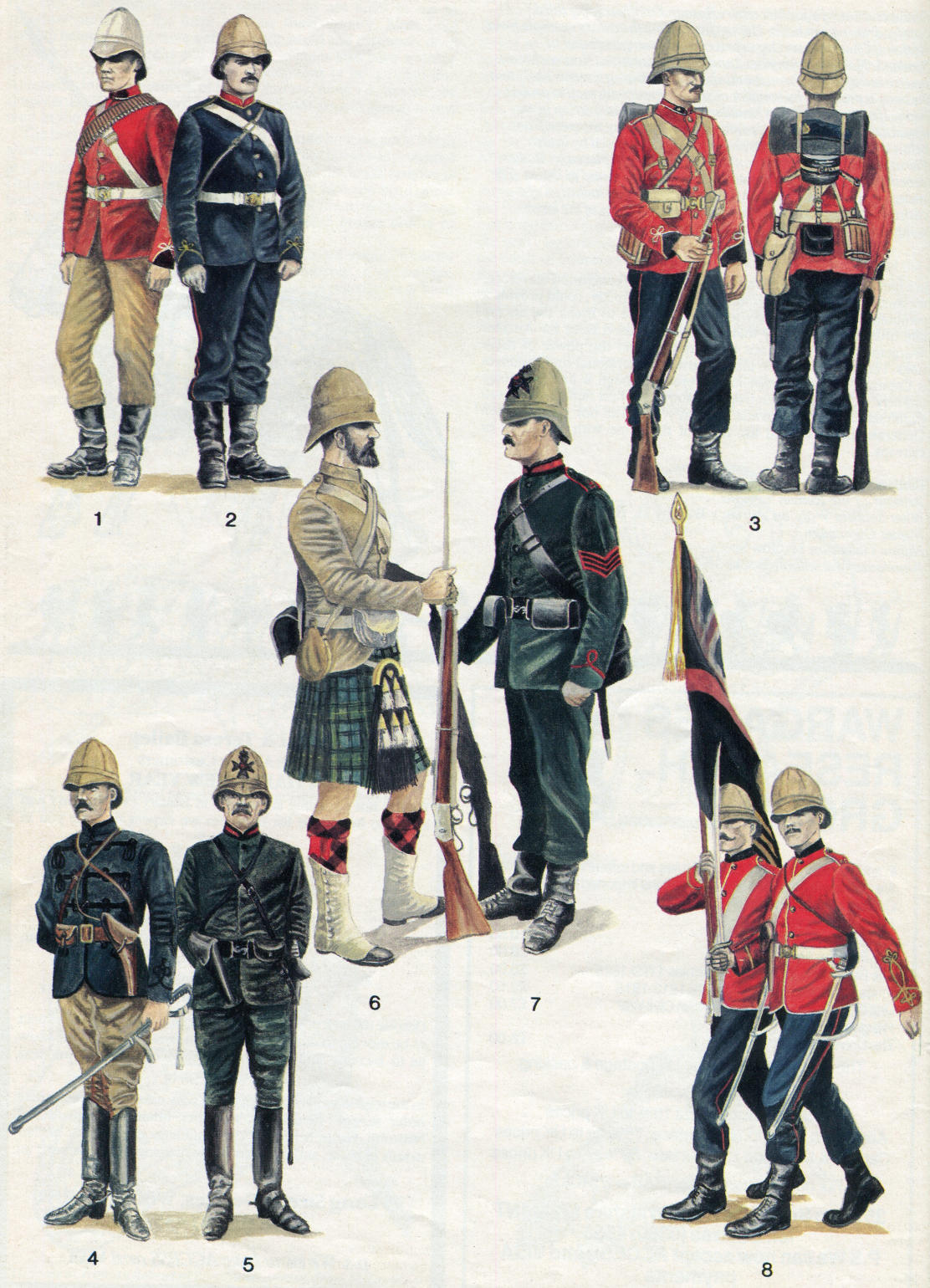

Uniforms of the First Boer War, 1881

by Ian Knight (Artwork by Cliff Weaver)

Miniature Wargames No. 32, January 1986.

Ian Westwell’s article which appeared in issue 21 of Miniature Wargames was an excellent introduction to a very little known Colonial campaign. Brief, unsuccessful and lacking the glamour of a Rorke’s Drift or Isandlwana to remember it by, the First Boer War has not received much attention so far from wargamers, and the uniforms of the troops involved are not widely known.

Ian Westwell’s article which appeared in issue 21 of Miniature Wargames was an excellent introduction to a very little known Colonial campaign. Brief, unsuccessful and lacking the glamour of a Rorke’s Drift or Isandlwana to remember it by, the First Boer War has not received much attention so far from wargamers, and the uniforms of the troops involved are not widely known.

In many respects the First Boer War was the final chapter in a period of history overshadowed by the Zulu War. It had been caused by the desire of the British government to form a confederation of white states in South Africa. Partly under the excuse that it was unable to defend itself against the threat of Zulu attack, the Boer Republic of the Transvaal had been annexed in 1877. The Zulus had been defeated in 1879, but not before they had massacred a British column and caused such an outcry that the confederation policy was dropped. In such a light the dismal little campaign which won the Boers their independence again in 1881 appears hardly more than an appendix in a story whose main plot has already moved on.

Certainly General Sir George Colley lacked the resources which Lord Chelmsford had had to defeat the Zulus three years earlier. With the exception of the 92nd (Gordon) Highlanders, all of Colley’s troops were Zulu War veterans. The 21st and 94th Regiments had spent several years in dreary garrison duty in the Transvaal, and large numbers of them were besieged in towns across the country at the start of hostilities. To march up from Natal to their relief, Colley originally had little more than the 58th Regiment and 3rd Battalion, 60th Rifles, since the 92nd did not arrive until the eve of Majuba.

Despite a number of significant uniform changes instituted in 1881, the bulk of these troops were wearing the same campaign dress they had worn in Zululand.

For the 58th, 94th and 21st — who, although a Scottish Regiment, did not adopt trews until after 1881, and at this time were indistinguishable from English infantry, apart from a red and white diced band on their Glengarry caps — this meant a white sun helmet, scarlet jacket and blue trousers.

The jacket came in two types, a dress tunic for formal occasions, and an undress frock for everyday work and actual fighting. The undress frock was scarlet, with five buttons down the front. Each regiment had a distinctive facing colour - black for the 58th, blue for the 21st, Lincoln Green for the 94th — and this was worn on a small tab on either side of the collar opening, and on a pointed patch on the cuff. The cuff was piped with white braid, ending in a trefoil loop over the point, and there was white piping along the bottom edge of the collar and all around the shoulder strap, and a brass collar badge on the tab.

The dress tunic was similar, but rather longer and smarter, and had seven buttons rather than five. It was piped down the front and up the two back vents on the skirt.

NCOs chevrons were worn on the right sleeve only, and were white for Lance Corporal and Corporal, and gold for Sergeant. Sergeants wore a darker red sash over the right shoulder.

Trousers were dark blue with a thin red stripe, and gaiters and boots black leather.

Equipment was the 1871 Valise Pattern, although the valise itself was not worn in South Africa, but rather carried on regimental transport wagons. The equipment consisted of a waistbelt in buff leather with two ammunition pouches on either side of the clasp. A brown cork ‘Oliver’ pattern water bottle was worn over the left shoulder, and a white haversack over the right. Buff braces supported a grey greatcoat and blue glengarry and a mess-tin in a black leather container. The bayonet was worn in a black scabbard on the left hip, and another ammunition pouch, the black ‘expense’ pouch, was worn either at the back of the belt or at the right front, below and slightly behind the buff pouch. The 58th apparently wore all this into action at Laing’s Nek, and figure 3 represents a private in this battle.

For all troops, apart from the 92nd, headgear was a white sunhelmet, from which the brass plate had been removed, and which had been rendered less conspicuous by improvised dyes, made from mud, tea, coffee, boiled mimosa bark, and even cow dung!

Infantry officers either wore their own version of the undress frock, or a blue patrol jacket. Figure 8 shows two Lieutenants of the 58th wearing the undress frock. This was scarlet, with plain scarlet cuffs, but with the whole collar faced the regimental colour. Rank was indicated by gold braid on the sleeves. The frock was piped white down the front, all round the bottom, and up the back vents and around the shoulder straps. The numerals on the shoulder straps were embroidered.

The infantry patrol jacket (figure 4) was dark blue, with black braiding across the front, round the cuffs, and up the back seams. At this time it had no shoulder straps.

Mounted officers wore riding breeches of buff cord, reinforced with leather on the inside leg. Revolvers were carried in brown leather holsters, either attached to the waistbelt or worn over the shoulder on a brown strap. Ammunition was carried either in a brown pouch on the waistbelt, or in a black cartridge box suspended from a white shoulder belt. Swords were in steel scabbards hung from white slings.

The 60th Rifles (figures 5 and 7) wore a uniform officially described as rifle green, but in fact nearly black, since great difficulties were experienced in obtaining a reliable green dye, and it was not until the 1890s that the familiar ‘rifle green’ colour we know today emerged.

The Rifles frock had a single loop of red braid on the cuff, red piping round the shoulder strap, a red battalion number, and a red collar, edged black. The officer’s version of the same thing had no braid on the cuffs, and no shoulder straps. Unlike Line Regiments, the Rifles wore chevrons — black on red - on both sleeves. All Rifle equipment was of black leather, and the ammunition pouches on the waistbelt were of a slightly different pattern, having a flap which covered the whole of the front of the pouch. For Line Regiments, ORs had a triangular socket bayonet for their Martini-Henry rifles, and Sergeants a heavier sword bayonet, but for the Rifles all ranks had the sword bayonet.

The helmet plate for the Rifles consisted of a black Maltese Cross, with a red centre, over which was a black bugle device. Photos of Rifle NCOs in the First Boer War suggest that they retained more helmet plates in action than did other regiments.

The 92nd Highlanders (figure 6) wore a completely different uniform, rushed to South Africa as they were from active service in the 2nd Afghan War. Despite some rather dubious painting showing them in scarlet, several eye-witness accounts refer them to wearing their khaki India-pattern uniform.

This consisted of a loose, pale khaki jacket, with no facings, piping or braid. Unlike other regiments, the 92nd wore a puggree on their helmets — it was authorised for India, but not for South Africa — and the whole thing was covered by a khaki canvas cover. The kilt was of the Gordon tartan, and the hose diced black and red. The sporran had black tassles on white hair for officers, and white tassles on black for others. Equipment seems to have been the older ‘pouch belt’ type, with a single ammunition pouch at right front, and a black cartridge box at the back. A haversack was worn over the right shoulder, and a soda-water style water bottle, covered in buckram, over the left. Officers wore a similar uniform to that of the men, a brown Sam Browne belt replacing the equipment. At Majuba the regiments wore blankets en banderole.

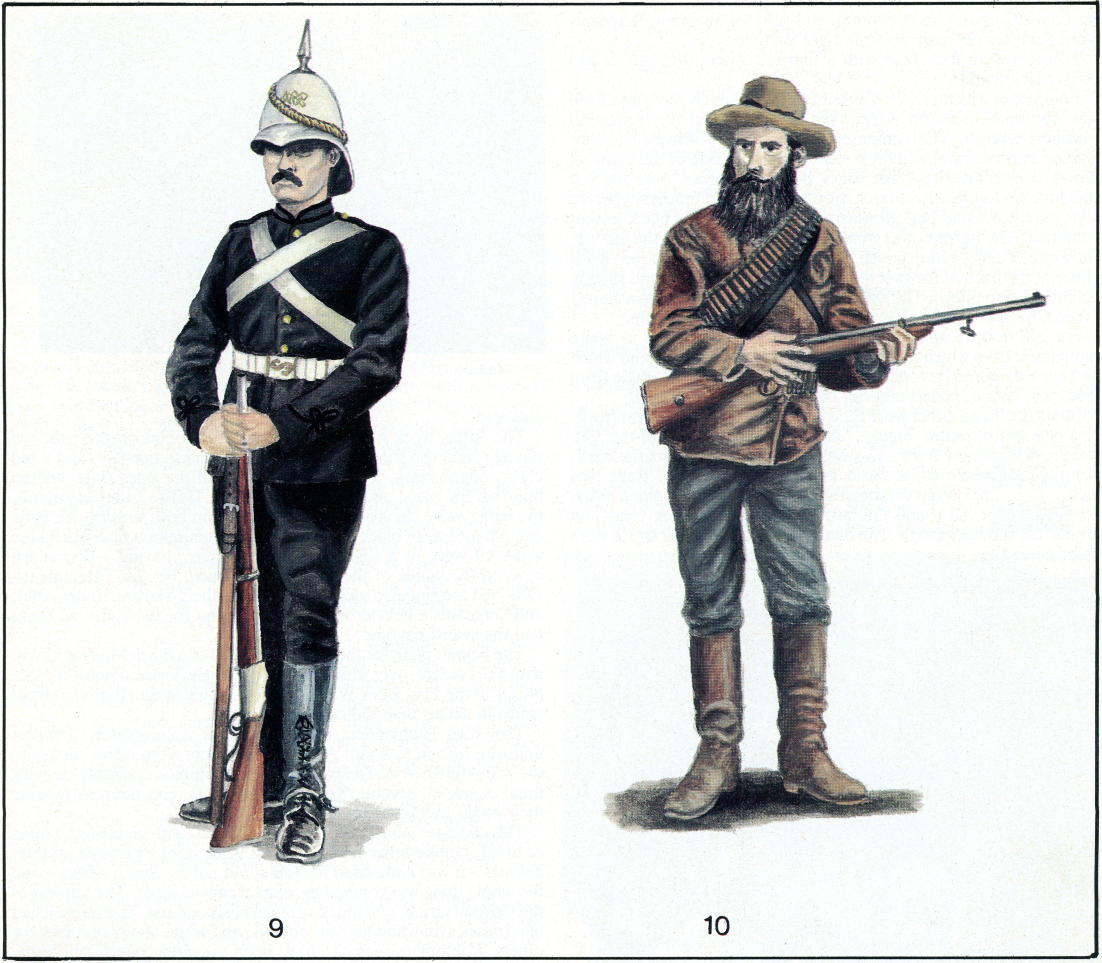

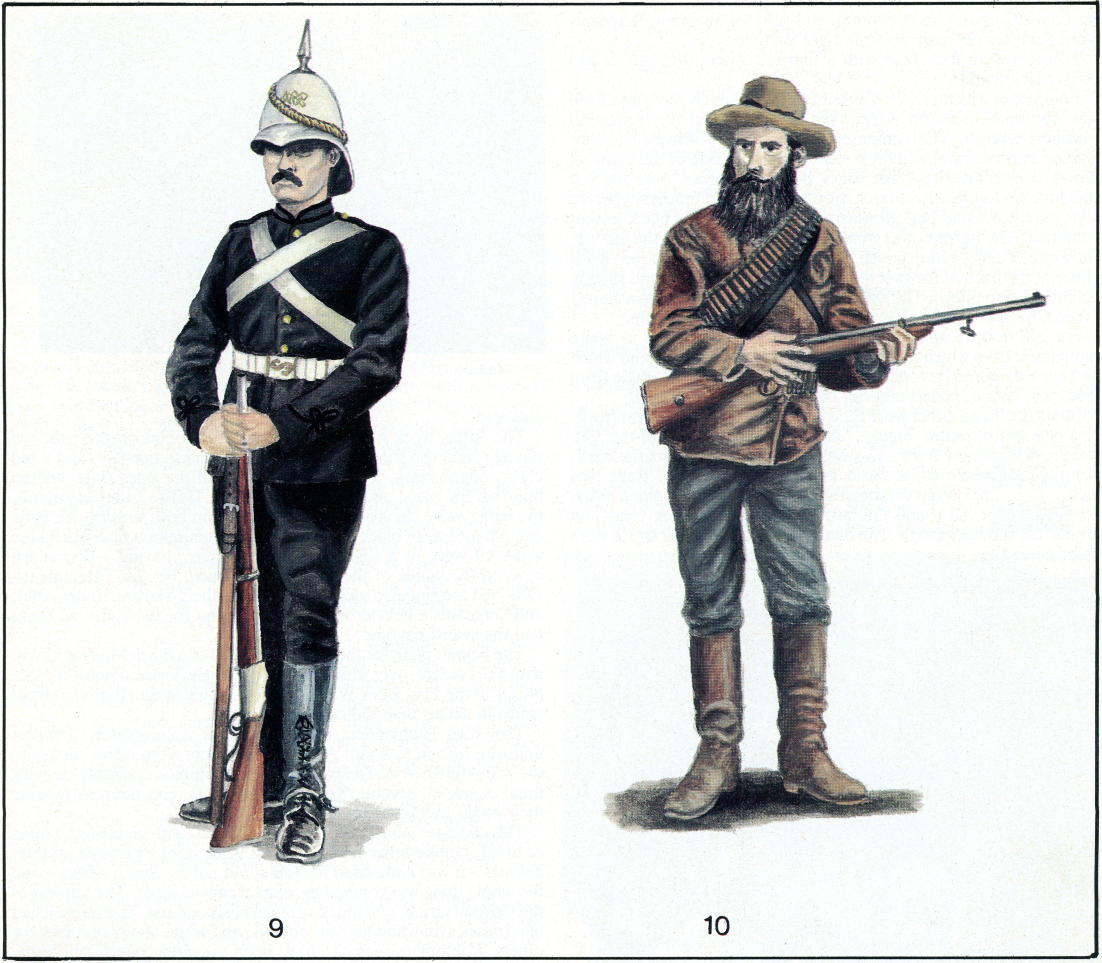

Colley, even more than Chelmsford before him, was chronically short of cavalry. He had only one weak squadron of the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards, who seem to have worn the same uniform they had in Zululand (of which more, I hope, in a future MW!), namely a scarlet jacket with blue collar, cuffs and shoulder straps, with yellow braid for ORs and gold for Officers, and blue trousers with a yellow stripe, black boots and white helmet. To augment these, Colley scratched together a Mounted Infantry company (figure 1), who wore the infantry jacket of their original regiment, with a leather loop-style bandolier and buff cord riding breeches. They carried a Martini-Henry carbine. Unlike Chelmsford, Colley did not employ large numbers of local volunteer units, with the exception of the 70-strong Natal Mounted Police (figure 9), who wore a black cord uniform with black braid, and a white helmet with brass fittings. It was felt, with some justification, that to use local volunteers would only cause problems between settlers and Boers once the fighting had ceased. Similar motives prevented both sides from employing blacks in combat duties — it was felt wiser to keep the prospect of a native rising firmly in the closet by fighting a ‘white man’s war’ — although both British and Boers used them in large numbers as support facilities, scouts, wagon drivers and so on.

For artillery support Colley had two 9-pounders and two 7-pounders of N Battery, 5th Brigade, Royal Artillery, the battery which had fought earlier at Isandlwana. The men wore a blue frock with a red collar, and yellow braid on the cuffs, collar and shoulder straps; Trousers were dark blue with a red stripe (figure 2). Officers wore a dark blue patrol jacket, which was similar to the infantry pattern, but had a different style of braiding, the frogging on the front ending in a trefoil rather than hanging loops.

At Majuba, Colley also had the services of some 64 men of the Naval Brigade. Rather less well documented than their Army colleagues, these are shown in one drawing wearing white helmets, but probably wore the same straw hats that they had in Zululand, and a blue sailor’s uniform.

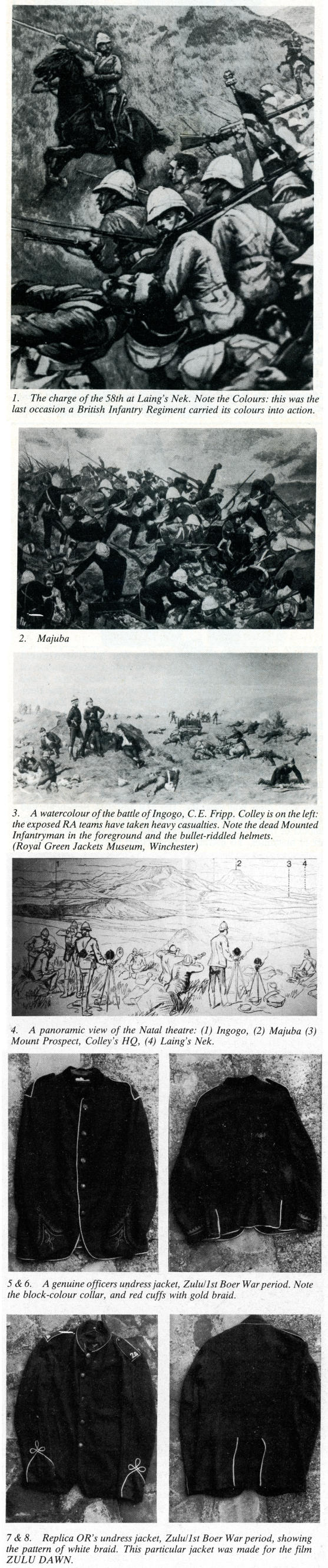

The Boers, of course, wore no uniform, preferring to fight in their everyday clothes (figure 10): jackets, trousers and hats of various shades of brown. It’s interesting to note, however, that the Boers of 1881 do look distinctly different to their more familiar counterparts in 1899. Jackets are of an older cut, beards are longer, and hats sometimes wider. The familiar pouch-style of bandolier was not worn in 1881, but rather the old loop style.

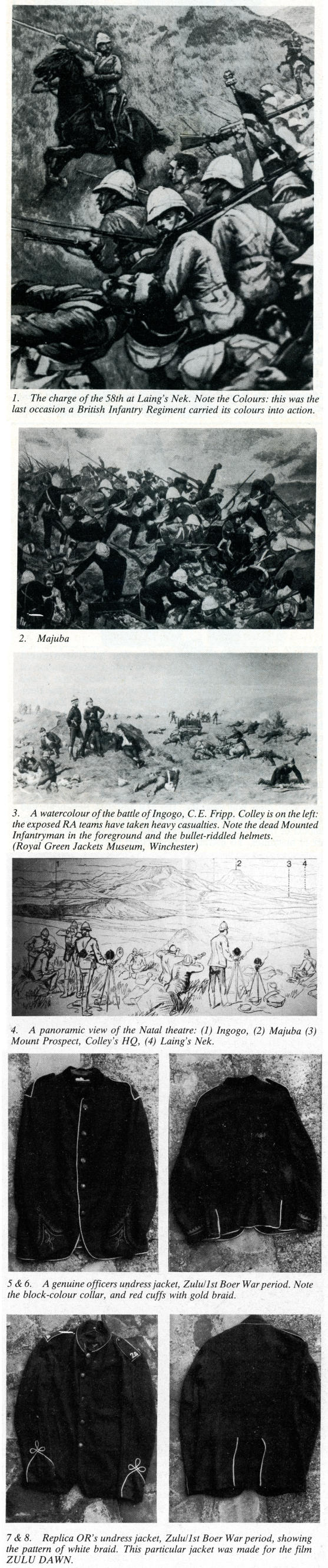

It’s often said that Colley lost the First Boer War because of the gaudy uniforms of his men. This is an obvious conclusion to jump to, but it doesn’t bear too much close examination. The much maligned scarlet tunics were not as conspicuous is often quoted, simply because they faded in the sun, became faded in dust, and generally toned in with South Africa’s rich red soil. Far more obvious were the white sun helmets, which bounced off the bright sunshine and could be seen hundreds of yards away, a glaring target. This is of course why the troops tried to dye them; they were only marginally successful, for at Ingogo many helmets were found shot to pieces.

Colley’s unimaginative tactics must take a certain amount of the blame, for any charge against an entrenched position, as at Laing’s Nek, must prove costly. And the Boers were very good shots; at Bronkhurst Spruit one man had no less than eighteen entry and exit wounds, having been shot nine times (he survived, incidentally!), and at Laing’s Nek one only has to look at the carnage wrought among the Colour Party to realise how adept the Boers were.

But the British suffered in the 1899 war too, but went on to find tactical solutions, and discover that a bayonet charge, properly handled, was by no means impractical even against the Boers.

The real reason for the defeat seems to have been that Colley was not a very good general, certainly not an experienced one, and most of his men knew it. ‘A malaise seems to have spread through the Natal Field Force and robbed the troops of the same dash and vigour they displayed in the Zulu War. To face a hoard of charging natives and die back to back in the open was one thing, but it required a certain inspiration to maintain momentum against hidden European sharp-shooters, and Colley didn’t have it. Taking Majuba was a good idea tactically, but it was badly mishandled, as almost every position other than the one which was defended would have been an improvement. The troops should have been dug in in advance of the skyline, or even on the plateau, out of sight from the slopes, but they should not have been on the very edge, where every move exposed them in silhouette. And the rag-bag nature of the force didn’t help — a single regiment might have had some cohesion, but in the mixed band Colley led to the summit, no one seems to have had much idea of what to do, and Colley himself failed to provide it.

For wargamers, the First Boer War has a lot of potential, if only because — if you use a small enough scale, and a large enough table — it should be possible to represent the whole Natal theatre in one, from Ingogo to Majuba. And figures abound in plenty, from Zulu and Afghan War ranges. Remember that figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ,7, 8, 9 and even 10 here are wearing the same uniforms that they did in Zululand.

Further reading

In addition to the SA Military History Journal and Oliver Ransford’s Majuba Hill, already mentioned in MW, there is Joseph Lehman’s The First Boer War (Jonathon Cape, 1972), a good general history, but with a rather jaundiced view of the British military. The standard contemporary history is Lady Bellairs’ The Transvaal War of 1880-1881 (reprinted by Struik in 1972). For those who wish to take it further, the Victorian Military Society’s Centenary Special, Forged in Strong fires, is recommended, as is David and Goliath by George R. Duxbury, published by the South African Military Museum in 1981.

See also 19th Century Illustrations of Costume and Soldiers

Ian Westwell’s article which appeared in issue 21 of Miniature Wargames was an excellent introduction to a very little known Colonial campaign. Brief, unsuccessful and lacking the glamour of a Rorke’s Drift or Isandlwana to remember it by, the First Boer War has not received much attention so far from wargamers, and the uniforms of the troops involved are not widely known.

Ian Westwell’s article which appeared in issue 21 of Miniature Wargames was an excellent introduction to a very little known Colonial campaign. Brief, unsuccessful and lacking the glamour of a Rorke’s Drift or Isandlwana to remember it by, the First Boer War has not received much attention so far from wargamers, and the uniforms of the troops involved are not widely known.