Find the perfect fit with Amazon Prime. Try Before You Buy.

The 1859 Italian War

Operations Of War

by Luigi Casali

Minature Wargames, October 1987

The Italian Second Independence War broke out with the declaration of war sent by the Austrian Government to the Kingdom of Sardinia at the end of April 1859. The ten years of peace which followed the end of the First Independence War (1848-1849) did not shatter the aspiration of Piedmont to go on with the struggle against the Austrian rule in Italy. The Piedmontese minister, Camillo Benso count of Cavour, was aware that Piedmont was too little to challenge alone the great Austrian Empire. So he looked for a strong ally for the inevitable next war against Austria. To this aim, Piedmont sent an expeditionary corps of 15,000 men to participate in the Crimean War. During the following years Cavour succeeded in convincing Napoleon III to sign a treaty of defensive alliance (January 1859). France engaged to come to the help of Piedmont if it were to be attacked by Austria. Cavour acted with great ability to provoke Austria. Piedmont put its army on a war footing and began to enlist the volunteers who poured from all over Italy and particularly from Lombardy and Venetia, the regions directly ruled by Austria.

The Austrian Government fell into the trap. On April 23rd, 1859, an ultimatum was sent to Piedmont. Austria demanded Piedmont to bring its army onto a peaceful footing and to send back to their homes Lombard and Venetian volunteers; otherwise war would be declared three days after. This was the occasion Cavour waited for. Piedmontese Government rejected the ultimatum. France let the Austrians know she would have considered as a war declaration the crossing of the Piedmontese border, marked by the Ticino river, by their troops. Yet Austria had carried things too far to retire without losing face. On April, 29th, Austrian vanguards crossed the Ticino river and entered Piedmont.

Since the first months of 1859 Austria had been strengthening her forces in Italy. At the beginning of the war the Austrian CC. Field Marshal Giulay had at his disposal the 2nd Army. This comprised of five army corps: the 5th (F.M. Stadion), the 7th (F.M. Zobel), the 8th (F.M. Benedeck), the 3rd (F.M. Schartzenberg) and the 2nd (F.M. Lichtenstein). As reserve there were the cavalry division of General Mensdorffs, the infantry division of General Urban, the reserve of artillery of General Herle and some units of Pioneers. Austrian forces totalled about 140000 men and 536 guns. Three more army corps were expected: the IXth. (F.M. Schaffgottsche), the 1st (F.M. Clam Gallas) and later the XIth (F.M. Weigl).

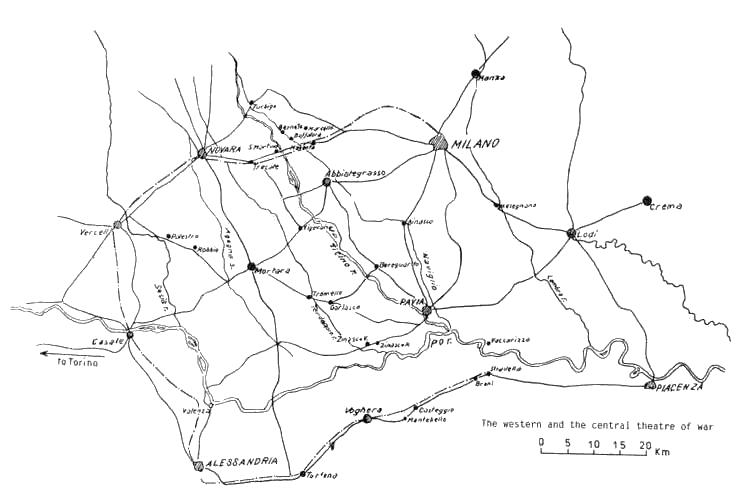

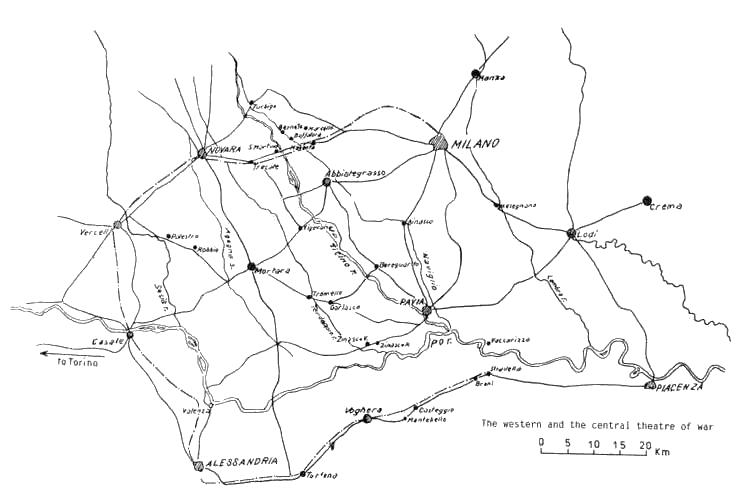

At the end of April Austrian forces were disposed behind the Ticino river, around Pavia. At this moment they were confronted only by the little Piedmontese army; this comprised five infantry divisions, one cavalry division and the Corp of Cacciatori of the Alpi, with a total force of about 60,000 men. The Piedmontese were drawn up on the right bank of the Po river between the fortresses of Alessandria and Casale.

The Austrians had projected to strike the Piedmontese Army before the French arrived in Italy. On April 30th, the main Austrian army crossed the Ticino river between Pavia and Vigevano and advanced into Piedmontese territory. On May 3rd, the Austrians reached the confluence of the Sesia river with the Po river. Yet the Austrian advance had been too slow and hesitating, precious days had been lost with useless marches. In the meantime French troops were landing at Genova or were crossing the Alps. F.M. Giulay lost more days in determining what to do. Finally he resolved to stop the operations against the Piedmontese Army and to march to Turin on the left bank of the Po river.

On May 6th the 5th Army Corp crossed the Sesia river to cover the left flank of the 7th Army Corps. This moved the day after. But the advance of the Austrians was greatly slackened by the terrain which was covered with flooded rice fields and by artificial interruptions caused by the Piedmontese. Giulay relinquished his plan and resolved to gather together the 2nd Army around the town of Mortara; the Austrian left flank leaned to the Po river and the right one to Vigevano. In the meantime the French Army joined the Piedmontese. Now the problem for Giulay was to foresee the movement of the Allies and the direction of their attack. He feared a manoeuvre on the right bank of the Po river, to cut off his own lines with Austria. To secure his left flank an Army Corp was sent between Stradella and Piacenza; the Urban division was sent to Broni. As Giulay needed clearer information about the movements of Allies, he ordered F.M. Count Stadion to do an offensive reconnaissance toward Voghere.

The battle of Montebello

On May 19th the Austrians went out from the fortified bridge head of Vaccarizz on the Po river. The next day they moved toward Voghera disposed three columns. On the right side the column of Prince Hesse marched. It comprised the 4th Kaiser Jager battalion, four battalions of the 31st Line Inf. Rgt.. Culoz, one battalion of the 6lst Line Inf. Rgt.. Zobel, three squadrons of König bei Sicilien Ulans and twelve guns, totalling of about 5000 infantrymen and 480 cavalrymen. The division of F.M. Baron Paumgartten marched on the centre. It comprised the brigade of the M.G. Gaal (1st batt. Grenzer Licaner 2nd btl. of 49th Line Inf. Rgt.. Hess, four battalions of the 3rd Line Inf. Herzog Karl, two squadrons of Hailer Hussars and twelve guns) and that of M.G. Bils (2nd btl. Grenzer Oguliner, three btl. of 27th Line Inf. Kinsky and eight guns), totalling about 9,950 infantrymen, 230 cavalrymen and 20 guns. The column on the left side was composed of the division of F.M. Urban. This comprised the brigade of M.G. Schaffgotsche (3rd Jager btl., one battalion of the 39th Line Inf. Don Miguel, the grenadier battalion of the 59th Line Inf. Raineri, two companies of Grenzer Sluiner, two squadrons of hussars of Hailer, four 12 pd. guns and four rocketeers), and that of M.G. Braun (three battalions of the 40th Line Inf. Rossbach and eight guns), with a total of 6700 men, 225 horses, 12 guns and 4 rocketeers. Opposing Allied forces comprised the First French infantry division of gen. Forey. It was composed of the Beruel brigade (17th. Chasseurs, 74th and 84th line infantry for a total of seven battalions) and the Blanchard brigade (91st and 98th Line Inf. and one battalion of the 93rd line inf), a squadron of "Chasseurs d’Afrique" and two batteries (with six guns each). The Piedmontese were present with eight squadrons of light cavalry (3 sqds. of Novara Cavalleggeri, 4 sqds. of Aosta, 1 sqd. of Monferrato Cavalleggeri). Allied forces totalled 6,900 infantrymen, 160 Chasseurs d’Afrique, 750 Italian light cavalrymen and 12 guns.

The battle field consisted of a levelled terrain north of the road from Voghera to Casteggio; yet it was broken by ditches, streams and little ravines which had many steep banks, difficult to cross; frequent mulberry cultivations reduced the visibility. To the south of the road were hills with vine plantations.

At eleven a.m. the heads of the Austrian columns were marked out at the villages of Calcababbio (Hesse column), of Casatisma (Paumgarten division) and of Casteggio (Urban column). The Italian cavalry was ranged as a screen in an advanced position before Voghera, where there was the main part of the French infantry. Two battalions of the 84th. were ranged on the road from Montebello to Voghera.

The battle began when the Austrians attacked on the eastern side of Casteggio a barricade defended by a hundred civilian volunteers. The Austrians positions two guns and after a short fight dispersed the enemies. The Austrians resumed their march but as soon as they poured out from Casteggio they were charged by two squadrons of Novara Cavalleggeri and forced to stop their march. The Piedmontese cavalrymen were counter-charged by two squadrons of Hussars of Haller. After brisk fighting the Austrians were pushed back on the infantry. The Piedmontese retired to rally. The Austrians continued their march but the advance was repeatedly delayed by further charges of Piedmontese cavalrymen. At the end the squadrons of Novara retired on the two French battalions of 84th infantry. The Austrians occupied Montebello and the high grounds of Genestrello. In the meantime the column of prince Hesse was being charged by the four squadrons of Aosta Cavalleggeri. After some short and brisk fighting with the squadrons of Ulans, the Piedmontese retired satisfied having acquitted their task at slowing the advance of the enemy. In the meantime Gen. Forey was moving from Voghera with two battalions of the 74th to help the battalions of the 84th, which were now going to be engaged by the Austrians. The squadron of Monferrato Cavalleggeri preceded the French infantry. The remainder of the French division was moving on too.

The French vanguards, supported by the Piedmontese cavalry, scarcely succeeded in repelling the Austrian attacks. Then, with the arrival of the remainder of its division, the French counterattacked. The line of fire now extended from the northern side of the road Voghera-Casteggio to Genestrello. A fierce fighting with bayonet charges and strenuous fire took place. Some farms were taken, lost and taken again. The Austrian troops disposed before. Genestrello withstood with great valour but at the end the “furia francese” prevailed and the enemy was repelled to Montebello. Stadion now ordered Hesse to converge on his left to Casteggio. The Gaal brigade, which had marched in the meantime toward Casteggio, occupied the left side of Montebello. The French were now risking being outflanked on their left flank by the column of Prince Hesse which was coming from Calcababbio; the indecision of the Austrians and the intervention of the squadrons of Novara and Monferrato foiled the danger; the Piedmontese cavalry charged the enemy artillery and infantry which formed squares of companies. At that moment the 1st battalion of the 93rd Line Inf. (div. Autemerre) entered in line; its arrival foiled definitively the outflanking manoeuvre.

After the conquest of the high ground before Montebello, Forey pushed on his battalions against the village. An Austrian counterattack repelled the French infantry. These renewed their attack with more determination. Bitter fighting took place in the streets, in the gardens and house to house. Finally at 6pm, the Austrians retired, protected by some troops ranged on the main road and by four companies of the 1st batt./3rd. infantry Rgt.. Herzog Karl, by a battalion of the Liccaner Grenzer Rgt.. and by two howitzers posted in the cemetery of Montebello that had a brick wall, With a last effort the exhausted French infantry took this position with a bayonet attack. In this action Gen. Beuret died. At seven p.m. F.M. Stadion ordered a general retreat to Cavvarizza and Stradella. The French returned to Voghera; the Piedmontese cavalry remained at Montebello.

In this little battle the Allies lost 750 men, dead, wounded or prisoners; the Austrians lost about 1,400 men.

As a consequence of the battle of Montebello F.M. Giulay became definitively convinced that the Allies intended to operate on the right bank of the Po river in the direction of Piacenza to outflank his left flank. Accordingly Giulay brought his ‘gravity’ centre toward the Po river. Just the same day, on May 20th, Napoleon, who had assumed the command of Allied armies, had planned to outflank the Austrian right flank, being the opposite side to that supposed by Giulay, with a manoeuvre from Vercelli and Novara toward Magenta and Milano.

In the meantime Garibaldi with his Cacciatori of the Alpi had been marching in direction of the Lombards. Perhaps with the task of rising the population against the Austrians and to attract to this secondary front enemy forces. On May, 23rd, Varese was liberated. Giulay, alarmed by this movement, sent the Urban division, which was at Broni, to intercept the Cacciatori of the Alpi. The first fighting took place on May, 25th, before Varese; it resolved with a defeat for the Austrians who retired to Como. This town was liberated by Garibaldi two days after with a circling movement which cheated Urban, who was defeated another time at San Fermo. The Austrians retired to Monza.

The battle of Palestro

The outflanking manoeuvre of Napoleon had to begin on the 26th of May. The Piedmontese army reinforced with the 3rd French Army Corps was charged to protect the French right flank and the important railway junction of Vercelli by crossing the Sesia river to attack toward the villages of Palestro, Vinzaglio and Confienza;

On 26th of May French troops were carried by train from Alessandria to Vercelli, from where they went on by foot to Novara. Giulay had only vague information of these movements. He was convinced it was only a demonstrative action on the Sesia river to make possible the crossing of the Po river by the French at Valenza, between Casale and Alessandria. So the sudden Piedmontese offensive surprised him completely. On May 30th, the Piedmontese crossed the Sesia river with four divisions. The 4th division (Gen. Cialdini) and the 3rd one (Gen. Durando) attacked respectively the villages of Palestro and Vinzaglio.

These two villages were set on a higher level than the surroundings. The zone was planted with rice fields completely flooded, so advance was hindered by the difficult terrain which favoured defensive tactics. Palestro and Vinzaglio were occupied only by a few Austrian units. At Palestro there were three companies of line infantry with two pieces; Vinzaglio was occupied by one company and a half. The Piedmontese attacked late in the morning. The Austrians were forced back by the numerical superiority of the enemy after a good defence.

F.M. Giulay continued to think the Piedmontese attack was only a diversional manoeuvre. He resolved to send an offensive recognition to know more exactly the intentions of the Allies. F.M. Zobel, who commanded the 7th Army Corp. was ordered to attack Palestro on the 31st with the Jellacic and Lilia divisions.

F.M. Zobel formed three columns. The central one was the principal. It was composed of four battalions of the Dorndorf brigade and four ones of the Koudelka brigade (see the detailed order of battle at the end of this article); this column had to attack along the road running from the village of Robbio. The right column was composed of the Weigl brigade; it had to attack from Confienza; the left one, composed of five battalions of the Szabo brigade, had to attack Palestro from the south-east.

Austrian forces totalled about 14000 men with 40 guns. General Gialdini had at his disposal the 4th division totalling about 10,700 men and 18 guns. in the course of the battle the 3rd Zouaves regiment would have added to the Piedmontese forces with its three battalions (about 2000 men)

Cialdini had ranged two battalions of the 10th Line Inf. astride the road running from Robbio on the edge of the plateau on which Palestro is situated. They were sustained by two sections of artillery. The other two battalions of the 10th line were ranged to support the first two ones. The 6th Bersaglieri battalion was ranged on the left flank. Two companies of the 9th Line Inf. occupied the cascina San Pietro (San Peter farm) on the extreme right flank. This farm had brick walled buildings; a solid brick wall connected them to each other; an outpost was set up at the Brida bridge on the Sartirana ditch. The 16th Rgt.. faced Confienza from the northeastern ridge of Palestro. The 7th Bersaglieri battalion, which had suffered heavy losses on the previous day, was left in reserve in the village. The 3rd Zouave Rgt.. had camped on the right bank of the Sesietta ditch.

Battle began at 10 in the morning, when the Austrian central column struck against the battalions of the 10th line infantry. The Austrian first line consisted of the 21st Jager battalion and of two battalions of the 22nd Line Inf. Wimpffen. The Piedmontese battalion on the right of the road offered a good resistance; it received help from the other two battalions of the regiment. These new units counterattacked and drove back the enemy. The battalion on the left side attacked by the Jagers and by the 3rd battalion of the 22nd did not withstand and retired to Palestro to rally. The Austrians followed but doing this exposed their right flank to a counterattack by the 6th Bersaglieri and by the 2nd battalion of the 15th Line Inf. and they were repelled. Then Zobel pushed on the 46th line of the Koudelka brigade; Bersaglieri and the 2nd battalion were driven back to the cemetery of Palestro where they formed a stand. Austrians were stopped by a deadly fire from the Bersaglieri and from some artillery pieces; then they were counterattacked by the 6th Bersaglieri and by two battalions of the 10th Line Inf. and were pushed in disorder toward Robbio.

In the meantime the fight had begun on the southern side of Palestro. The terrain around the San Pietro farm was impracticable due to some unfordable canals and ditches; the largest of these, the Sartirana ditch, was passable only at the Brida bridge, that the Piedmontese had neglected to guard adequately. General Szabo pushed on the 7th Jager battalion. This smashed easily the weak enemy outpost, crossed the bridge and attacked the San Pietro farm. The two companies of the line infantry in the farm offered a strenuous resistance. Szabo employed a grenadier battalion too, supported by two guns. Finally the Piedmontese were pushed off from the farm and retired to Palestro, followed by the Austrians. Yet the long resistance of the two companies at San Pietro had enabled Cialdini to move to the left flank the 7th Bersaglieri and the four battalions of the 16th line. Bersaglieri counterattacked the right enemy flank. The Austrians were pushed back to the San Pietro farm. At this moment the Zouaves of the 3rd regiment sprang out from the Sesietta ditch and attacked the left flank of the Austrian line. The French rush was overwhelming. Lead personally by King Victor Emmanuel II, who until that moment had been watching the battle from the bell tower of the church of Palestro, they struck Austrian troops engaged at San Pietro farm and those still drawn up on the road. At the same time the 16th Rgt. was attacking San Peter farm from the northern side; the Austrians, taken on their front and their left flank, offered a good defence but at last they could no longer resist and broke, flying to the Brida bridge; as this was already occupied by Zouaves, fugitives had no alternative than throwing themselves in the Sartirana ditch; many drowned or were taken prisoners. The Austrians lost all their guns.

General Weigl on the right flank did not have any greater success. At about 10.30am he struck against the vanguard of the 1st Piedmontese division posted at Confienza. Prevented from attacking, he succeeded in maintaining his positions until 0.30 pm repulsing some Piedmontese counterattack; this resistance saved Zobel’s troops from the major disaster which would have struck them if the Piedmontese had been able to precede them at Robbio or to attack their left flank while they were retiring from Palestro.

Allied losses were of about 450 Piedmontese and 300 Zouaves (dead, wounded or prisoners); those of the Austrians were heavy, about 1950 men, which was about 17 per cent of the total forces engaged (force and losses of the fighting on the Austrian right flank at Confienza are not enclosed in this count). The Szabo brigade alone lost about 1,000 men.

ALLIES Battalions Squad. Force Guns IV Division. B.G. Cialdini Regina Brigade 9th. Line Inf. 4 2217 10th. Line Inf. 4 1982 7th. Bersaglieri 1 533 Savona Brigade 15th. Line Inf. 4 2284 16th. Line Inf. 4 2159 6th. Bersaglieri 1 574 Alessandria Cavalleggeri Rgt.. 2 227 3 batteries 424 18 Engineers 2Co 300 TOTAL 18+2Co 2 10720 18 3rd. Zouave Rgt.. 3 2100 AUSTRIANS Jellacic Division Szabo Brigade 7th. Jager 1 698 12th. line inf E.H. Wilhelm 4 3591 7th. horse battery 8 Konig bei Sicilien Ulans 2 324 Koudelka Brigade 21st. Jager 1 711 46th. Line Inf. Jella 3 2512 10th. horse battery 8 TOTAL 9 2 7836 16 Lilia Division Weigl Brigade 53rd line in E.H. Leopold 3(14Co) 2380 2nd. foot battery 8 Kaiser Franz Joseph Hussar Rgt.. lplt 36 Dorndorf Brigade 2nd. Grenzer inf. Ottocaner 1(4Co) 780 22nd. Line Inf. Wimpffen 3 2752 3rd. foot battery 8 7th. rocket battery 8 Kaiser Franz Joseph Hussar Rgt.. 1 143 TOTAL 7 1¼ 6091 24 GRAND TOTAL 16 3¼ 13927 40

The battle of Magenta

Giulay wished to renew his attack against Palestro on June 2nd, with five divisions, but the day before he had noticed the French Army was massing at Novara. Finally he became convinced the enemy was going to attack his right flank. Giulay ordered to concentrate his scattered forces at Magenta as soon as possible. Austrian troops had to endure tiring forced marches that lowered their morale and fighting efficiency. Yet on the night of the 3rd of June, Giulay was able to mass around Magenta a force of about 50,000 men: brigades Burdina and Reznicek of the 1st Army Corp, all the 2nd Army Corp and the reserve of cavalry. Three other army corps (8th, 5th, 3rd) were placed at Abbietegrasso at 12km. far from Magenta.

These last troops would not have been able to mass quickly should it have been necessary. Giulay did not foresee having to fight a battle on the next day.

At the same time the French were throwing a pontoon bridge (some sources say two bridges) across the Ticino river near the village of Turbigo. General MacMahon with the 2nd Army Corp, the Voltigeurs Division of the Guard and the 2nd Piedmontese infantry division (Gen. Fanti) had to cross the Ticino river at this point and to march to Magenta with a circling movement. Napoleon III himself had to cross the Ticino at San Martino di Trecate with the Grenadier division and the 3rd and 4th Army Corps and move to Magenta. The right flank constituted by the 1st Army Corp and from other two Piedmontese divisions would have remained on the right bank of the Ticino river; the 5th Piedmontese division and one division of the 5th French Army Corp covered the Po river between Vercelli, Alessandria and Tortona.

Napoleon thought to outflank the enemy’s right flank on the left bank of the Ticino river to compel the Austrians to abandon the line along this river and the capital of Lombardy, Milan, without fighting. So the battle was unforeseen by both contending armies.

The battlefield was strewn with rice fields and woods; it was ploughed by the Ticino river which had sandy banks and from the Naviglio Grande, a canal which flowed from Turbigo to Boffalora. This canal was very difficult to pass as it was some metres deep and 10 metres wide; its banks were high and plumbed with stone masonry. It could have been passed only on the bridges at Turbigo, at Boffalora, at Magenta and at Robocco.

On the early morning of the 4th of June, the Grenadier division crossed the Ticino river at San Martino di Trecate; they drove back some Austrian troops and then advanced toward Magenta. Yet Napoleon was informed that numerous Austrian forces were deployed on the left bank of the Naviglio Grande, so the Emperor resolved to wait for the attack of MacMahon from the north.

MacMahon had crossed the Ticino river at Turbigo on the evening of the 3rd and on the morning of the 4th of June. The 1st division (Gen. La Motterouge) had to head for Boffalora, the 2nd (Gen. Espinasse) for Marcallo. The Voltigeur division of the Guard (Gen. Camon) followed the 1st division. The 2nd Piedmontese division had been delayed by the French baggage and train that obstructed the pontoon bridge. The columns of MacMahon marched incautiously without exploration, so the advance guard of the 1st division struck unforeseen against the enemy troops posted in the village of Bernate. La Motterouge smashed this first resistance and carried on his advance toward Boffalora but he was stopped at Monte Rotondo by the Reznicek brigade. MacMahon ordered to La Motterouge to deploy his division and to wait for the arrival of the other divisions.

At this point the fighting was at its height near Magenta. At 12am Napoleon had heard guns thundering toward Boffalora; he had thought it was the attack delivered by MacMahon and had ordered General Mellinet, commanding the First Division of the Guard, to attack the bridges of Ponte Nuovo of Magenta and Boffalora.

French Grenadiers advanced with great “elan” against Ponte Nuovo; Austrian troops which defended it were forced to retire on the left bank of the Naviglio. However the grenadiers did not succeed in crossing the bridge as they were repelled by the deadly fire from the Burdina brigade and from two howitzers which fired at point blank. A second attack launched with fresh troops was more successful. Grenadiers formed a bridge head on the left bank of the Naviglio Grande and the Austrians retired to Magenta. Yet a dangerous Austrian counterattack on the right flank was standing up, while MacMahon was delaying his attack. The situation for the French remained critical until four pm. At last the 2nd div. of Espinasse arrived before Marcallo and lined with the 1st division. MacMahon attacked with both divisions in the first line and that of the Guard in the second one. The attack of French was fully successful, They arrived on the outskirts of Magenta, which was conquered in the evening after long and bitter fighting in which general Espinasse was killed.

The Austrians retired in the night under the screen of the cavalry division of the Reserve. Tiredness from the hard fighting, obscurity and the Austrian cavalry prevented the French from following.

Forces effectively engaged in the battle were of about 45,000 men on each side. French lost about 4,5000 men, dead, wounded or prisoners. The Austrians lost about 10,200 men, of which 4,500 were prisoners.

The battles of Solferino and San Martino and the end of the war

After the defeat of Magenta, Giulay ordered a general retreat to the Adda river. Some days after the battle Napoleon and Victor Emmanuel entered Milan cheered by an enthusiastic crowd. The French advanced to Lodi. On the 8th of June bitter fighting took place at Melegnano between an Austrian brigade which acted as rearguard and overwhelming French forces. After hard and tenacious resistance the Austrians retired with heavy losses. Giulay, who now was supported by F.M. Hess, resolved to retire as fast as possible to Verona to join a new army that was being formed. The Allies followed.

In the meantime Garibaldi had prosecuted his private campaign against Gen. Urban. On June 11th Cacciatori of the Alpi entered Brescia. Then Garibaldi received the order to reach the village of Lonato near the Garda lake, but this movement exposed inevitably his right flank. Garibaldi informed the Piedmontese General Staff of this but he received no reply. Urban took advantage of this opportunity and attacked in the direction of the village of Treponti some battalions of Cacciatori which Garibaldi had disposed there to cover his right flank, After fighting for three hours Cacciatori of the Alpi retired. The Austrians did not follow, but on the contrary continued their withdrawal.

Kaiser Franz Joseph was very displeased with Giulay. He was removed from his command which was assumed by the Kaiser himself. F.M. Hess was Chief of the General Staff.

On June 21st the Austrian army was on the left bank of Mincio river. Two more Army Corps, the X (F.M. Werhardt) and the XI (F.M. Veighl), and the cavalry division of gen. Zedwitz had just arrived from Austria. Two Armies were organized; the 1st commanded by the F.M. Wimpffen. was composed of five Army Corps: the 2nd, the 3rd, the 4th, the 5th, the 6th and the division of cavalry Zedwitz; the 2nd Army commanded by F.M. Schlieck, was composed of four Army Corps: the 1st, the 5th, the 7th, the 8th and the cavalry division of general Mensdorffs.

On 22nd F.M. Hess was informed that a strong French vanguard had crossed the Chiese river. The Austrian General Staff, persuaded to surprise the enemy divided in two parts, resolved to cross the Mincio river to attack the Allied forces and beat them separately. As for Napoleon, he was persuaded the Austrians were still retiring and that the columns sighted at Solferino and San Martino were only the rearguard of the Austrian Army. The Allies resolved to attack on 24th.

The opponent armies found themselves facing each other suddenly, with troops ranged in columns of march. The units deployed themselves gradually as they entered into battle. The French fought at Solferino and the Piedmonteses at San Martino. Forces engaged were almost the same: about 150000 men in each army. The Austrians had the tactical advantage to occupy a row of hills from the village of San Martino to Guidizzolo. The French and the Piedmontese launched attack after attack against the Austrian positions. Finally after a day of bitter and bloody fighting in the course of which the effectiveness of the French rifled guns was in evidence by repelling a dangerous manoeuvre of the Austrian cavalry the Austrians were forced to retire.

Losses were 21,700 for the Austrians, of which 8,600 were prisoners, 5,500 for the Piedmontesses and 11,600 for the French.

The battles of Solferino and San Martino ended the war. Napoleon was troubled by the dreadful sight of the battlefield covered by thousands of bodies of dead and wounded men. The Emperor did not feel able to continue the war and on July 11th, signed with the Kaiser Franz Joseph the Armistice of Villafranca. Austria kept Venetia; Lombardy was annexed to Piedmont.

Wargaming the 2nd Italian Independence War

The two battles of Montebello and Palestro are very interesting for wargamers. Scenarios with bridges, villages, rice fields, ditches and rows of trees are very various. Troops involved were relatively few, so that a limited number of figures occurs. A ratio of 1 figure for 50 men is advisable. This scale will give a Piedmontese battalion of 12 figures, with four companies of 3 figures each. With suitable rules these would be engaged as independent units as the two ones of the 9th lines infantry which occupied the cascina San Pietro at Palestro. The Austrians will have from 18 to 24 figures for each battalion of six companies and from 12 to 16 figures for battalions of 4 companies. This will give 3 or 4 figures for each company and from 6 to 8 figures for a division. The French will have from 12 to 14 figures for a battalion, with six companies from 2 to 3 figures. A Piedmontese and a French squadron would have two or three figures and an Austrian one 3 or 4 figures. Artillery can be represented by one model for two pieces (a section).

The battle formation for this period was generally a wider line (chain) of two or three ranks, preceded by a screen of skirmishers. Some words are necessary for Bersaglieri. Although they were classified as light infantry they were often employed as assault troops. They were trained to fight in skirmish order or with more dense formation. This applied to Zouaves and Turcos and French chasseurs and Austrian Jagers and Grenzers too. Generally these troops acted as vanguard. The French and the Piedmontese preferred “cold steel” tactics. The Austrians favoured fire power; they fought in a three deep rank line. Platoons and piquets were often formed from the third line to act as skirmishers or as reserve.

As for rules the only one in English which are specific for this period are the Newbury ones for XIXth century wars; yet any set of A.C.W. rules can be used with some little modifications regarding morale and fire power.

As for morale, consider the same for the Austrian, Piedmontese and French line infantry, Border infantry and Jager. It would be a little higher for Austrian and Piedmontese and French grenadiers, Bersaglieri and Zouaves and Chasseurs and Kaiser Jagers. Give ‘elite’ status to French Guards. As for “elan” in charges, it would be advisable to give a higher one to French troops. As for fire the distinction between smooth bore and rifled guns is obvious. All Piedmontese line infantry, a part of Austrian line infantry and Grenzers (I suggest a forty per cent) had smooth bore muskets. All other troops had good rifled muskets and carbines. Jagers and Bersaglieri were good shooters. As for cavalry. You can give the same morale and fighting ability to all line and light cavalry, with some difference for lancers. Artillery was smooth bore, with the exception of the rifled French 4 inch. Artillery would have to be classified in heavy (16 pd, 12 pd, 15cm howitzers) and medium (6pd and 8pd), so to simplify, you could use only two tables for smooth bore and a special one for the 4 inch; this last had a greater range and more accuracy than others.

European XIXth century is a rather new period for wargaming, so manufacturers which produce figures for it are not so numerous as for other ones. In the 1/300 scale Heroic and Irregular produce figures suitable for this period. Heroic has the FrancoPrussian War range which gives good French. For Austrian line and Border infantry, Napoleonic British line infantry give a good line infantry simply by painting the tunic with white and trousers sky blue; to obtain Piedmontese infantry put some vinilic glue between the legs of the British line infantryman to have the greatcoat. Cavalry can be obtained from the Napoleonic one (for example for Piedmontese Dragoons use French Line Lancers) and Franco-Prussian War. Artillery comes from A.C.W. range and Franco-Prussian War. The Crimean range of Irregular fits very well to this period too.

As for 15mm at the moment I am writing there are three manufacturers which produce figures for this period: Pioneer, Peter Laing and Frei Korps.

Really Pioneers produce only Austrians for 1866 and French for 1870. They are good figures, but their 15mm is closer to 18mm than to a real 15mm. Peter Laing’s figures need no presentation. All wargamers know the figures by the ‘father’ of 15mm. In his extensive catalogue you will find many figures suitable for the 1859 war.

The best figures on the market are for those by the Frei Korps 15. This range is extensive and complete; it is the only one made specially for the Italian Wars from 1859 to 1866. Details of uniforms and equipment are perfect and the animation come out directly from the pictures and prints of that time; those figures are the best you can wish for your armies. Among these figures I like very much the Bersaglieri and the Piedmontese and the French line infantrymen. These figures and the other ones of the range catch really the spirit and the appearance of the soldiers of the Italian Risorgimento Wars.

As for 25mm there is a very good Italian firm, the Mirliton: it makes wonderful figures, which assemble the best Hinchliffe style. Their list of 1859 figures is complete for Austrians and Piedmontese. As I know the only British firm which produces some figures suitable for this period are those by the Wargame Foundry. At the moment I am writing it has French of 1870 but not Austrians and Piedmontese.

To end, two words are necessary about landscape and buildings. Houses and farms were of red bricks, sometimes covered with grey, tan or white-grey lime and plaster. All roofs were of red tiles. Farms had broad and solid brick walls.

Landscape from the western bank of the Ticino river to Piedmont was constituted by extensive rice fields crossed by roads and little dykes and grass fields. Rice fields were flooded until July. All roads were generally flanked by ditches, generally two or three metres broad and from one and half to two metres deep. Rows of trees, generally poplars, flanked the roads, the banks of ditches or divided fields from each other. The landscape from the eastern bank of the Ticino river toward Venetia is generally flat. Toward Solferino and San Martino it became undulated with vineyards and cultivations.