Prelude to the Battle of Austerlitzby Jeff VitousIntroduction

The Battle of Austerlitz in December of 1805 was the culmination of what is also known as the "Wars of the Third Coalition." This ill-fated alliance was the handiwork of British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, and included Great Britain, Russia, Austria, Sweden, Naples, and several smaller German states. The other continental power, Prussia, remained neutral throughout 1805, and Napoleon felt it imperative that the Coalition be defeated before the Germanic kingdom could be persuaded to join. The roots of the Third Coalition date back to the previous year. A popular Bourbon prince, the Duke d'Enghien, was kidnapped from exile in the German state of Baden by a cavalry patrol sent by Napoleon. The duke was then taken to the Chateau de Vincennes, where he was tried by a sham court martial and executed. All of Europe was outraged over the incident, and Napoleon was branded an outlaw by the other heads of state. Pitt, who had earlier been Britain's youngest Prime Minister, serving from 1783-1801, reassumed this role on the same day Napoleon was declared Emperor. Always an ardent opponent of Napoleon, Pitt would set about on a crusade against his nemesis that would lead to the heart-breaking defeat credited with causing the politician's premature death in 1806.

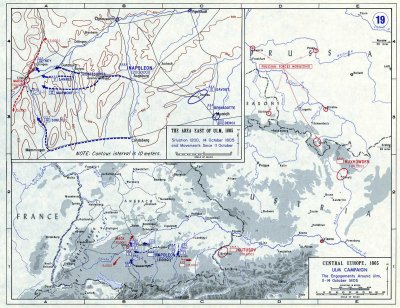

The goal of the Third Coalition was to not only halt French expansion, but to force her back to the territorial boundaries established in 1791. It was decided that the focus of land operations would be along the Austrian frontier in Germany and Italy, while for her part, England would concentrate on controlling the seas. Force Disposition - France A sizeable portion of the French army in mid-1805 was concentrated near Boulogne, ostensibly preparing for an invasion of England. Napoleon was unable to ever secure sufficient naval assets to make this threat possible. His annexation of the Ligurian Republic in the name of securing ships and sailors not only openly violated a treaty with Austria, but provoked Russia into fully committing themselves to the Third Coalition. Napoleon became concerned over Austrian troop concentrations, and decided that the continental threat must be addressed before it could solidify into an unstoppable force. A reserve army would be left at Boulogne under the command of General Guillaume Brune, continuing to hold up the appearance of an army preparing to invade England. In practical terms, this command consisted of infirm and under-trained or ill-equipped units. Meanwhile, the six corps comprising La Grande Armee would each follow a different path to the Austrian frontier. Marshal Bernadotte led the I Corps along a path that violated Prussian neutrality in Ansbach. While the Prussians would protest, they declined to press the issue, but in return would allow Russia forces to cross Silesia a few days later. Two Bavarian divisions under Wrede and Deroi would form a provisional corps, heading south from their starting point about 100 miles north of Munich. The remainder of La Grande Armee would advance in roughly parallel paths from the Rhine to the Danube.

*Augereau's VII Corps remained in northern France until after the Battle of Ulm. In Italy, 50,000 troops under Marshal Andre Massena was slated to keep Austria's most accomplished commander, Archduke Charles, from playing a significant role in the upcoming action. Force Disposition - Austria

The Austrian army was in the process of implementing reforms championed by its Quartermaster-General, Karl Mack. While the reforms themselves were prudent and necessary, doing so on the eve of a campaign proved to be the General's undoing. Confusion and disorder reigned as Mack severely underestimated his own army's capability as well as the size of the French. Force Disposition - Russia More than 100,000 Russian troops were mobilized in support of the Third Coalition in Austria. General Mikhail Kutusov, Russia's most experienced commander, commanded 36,000 troops approaching from southern Russia through Hungary. General Buxöwden approached from the northeast with another 30,000. Both of these commands were to link up with Ferdinand/Mack and engage La Grande Armee with an overwhelming numerical force. Meanwhile, General Bennigsen and 20,000 troops were camped on the Prussian border, hoping to encourage the Germanic nation to join the Coalition. Additional troops were scheduled to operate with Swedish allies, attacking through Pomerania, and with the English and Bourbon forces via Naples into southern Italy. None of the other events were to materialize, however, and the only forces to see action in the 1805 campaign were those of Kutusov and Buxöwden. Coordination between the allied armies was surprisingly poor. Timetables were set that required forces to come together at the expected moment to carry out the strategic plan, but the Russian Orthodox calendar was not taken into account, so at best, they were twelve days off the mark. Buxöwden was further delayed as he waited permission to cross Prussian territory in Silesia. Furious over Bernadotte's trespass of Ansbach, the Prussians were happy to comply, but this still caused another day's delay. On top of this, Russian troop movements were ponderous at best. Force Disposition - England It was England's intention all along to focus on gaining control of the seas, although they did promise some land forces to help spread the assault and keep France off balance. An army was to cross the channel, raiding the French coast and low countries, perhaps coming in via Hanover. Another force from Malta was to combine with 17,000 allied Russians, 36,000 Bourbons from Sicily, and some Albanian troops to invade and reconquer Naples, afterwards striking north to combine with Archduke Charles army. This force would then wipe out Massena's Army of Italy. The Ulm Maneuver The allied plan was predicated on a concentration of force which would overwhelm Napoleon in a pitched battle. Napoleon's plan was to disrupt this concentration, and defeat the allied contingents in detail. The Austrians began their offensive on September 2, moving into Bavaria and demanding that Elector Maximilian Joseph place the Bavarian army under Ferdinand's control. Mack advanced to the Iller River and began fortifying a position around Ulm, anticipating a French assault through the Black Forest, the traditional invasion route in the area. The Austrians were terribly disordered by even this short march, however, and with Kutusov's Russians nowhere in sight, Ferdinand requested the Austrians move back eastward. Mack, however, felt the position near Ulm was strong and advised they stay put. He did not imagine that France would dare violate Prussian neutrality and march through Ansbach. When Bernadotte's I Corps and the Bavarian divisions of Wrede and Deroi marched through Ansbach, Mack slowly came to realize that he was being surrounded. Convinced of an English landing near Boulogne and the impending arrival of Kutusov, Mack sat entranced, like a deer in headlights, as Napoleon drew a noose around the ill-fated army. Behind a cavalry screen deployed by Marshal Murat, the French corps moved into position, winning a series of frontier skirmishes against Austrian outposts. An error in deployment left General Dupont's division of Ney's VI Corps isolated near Haslach, but the 6,000 strong French force prevailed against two corps of Austrians under Riesch and Schwartzenberg (October 11). With the north bank of the Danube swarming with Austrian troops, Napoleon ordered a quick withdrawal. Meanwhile, Ney was ordered to capture the Elchingen Bridge, in support of Dupont's division. Here he was opposed by Riesch, and after heavy fighting, secured the bridge and drove Riesch back on Ulm. Soult's IV Corps was approaching from the south after taking Memmingen, and Marmont occupied the bank of the Danube opposite Ulm. Mack had misinterpreted Napoleon's abrupt withdrawal along the north bank as an indication that there were troubles in France or elsewhere. Ferdinand, determined that a Hapsburg not be captured by the French, took the cavalry and escaped northward, covered by a corps under the command of General Werneck. Another 5000 or so men under General Jellacic escaped the French noose by retreating southward. This left Mack and approximately 27,000 troops in Ulm. When a battered Riesch appeared with Ney dogging his heels, reality set in and peace negotiations began on October 15. A defiant Mack held that his position was strong, although food was scarce, the countryside was even more barren. With Werneck interfering with French supply, he need only hold out until the siege became untenable for the French or the Russian army arrived. His generals, however, disagreed, and began negotiating with the French. Mack agreed to capitulate on October 25 if relief did not arrive by then, but when presented with a clear picture of the situation, he gave in five days earlier. Murat was sent to clear the supply lines threatened by Werneck, and caught the Austrian baggage trains as well as their artillery. When the "unfortunate General Mack" and his 27,000 men turned in their weapons, the total prisoner count in the campaign rose to more than 50,000. Aftermath

Several events prevented Napoleon from catching his Russian prey. A provisional corps under Marshal Mortier was to advance along the north bank of the Danube, but was caught and engaged at Durrenstein. This could have been a disaster, since Mortier's corps was supposed to be covered by Murat's cavalry. Murat, however, decided to break off pursuit and capture Vienna. Murat once again caught the wrath of the Emperor when he was tricked by Russian rearguard commander General Peter Bagration into accepting a false armistice. Napoleon wanted these Russian units engaged and destroyed, and ordered Murat to break the armistice at once and attack. The ensuing combat at Schöngraben was a Pyrrhic victory for the French, another day lost, and their quarry had safely escaped. On November 20, Kutusov successfully linked with Buxöwden, forming an army of about 86,000. Napoleon's army was scattered, and he had perhaps 53,000 under his command. The French army was beginning to get stressed, and Napoleon could sense that some reorganization time would soon be needed. But indications were positive that the Prussians might join the coalition at any time; with another 200,000 troops, the allied army might well have been an overwhelming obstacle. The Russian army must be engaged at the earliest convenience, and the Austrians needed to be brought to the negotiating table. The stage was set for a decisive battle in the Moravian countryside near a small village known as Austerlitz. Battle of Austerlitz by Jeff Vitous ANGV Preview by Gary Morgan WNLB & ANGV Download Page Strategy Tips For Playing ANGV by Gary Morgan Index of Illustrations of Costume and Soldiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A secret treaty was signed in St. Petersburg on April 11, 1805,

officially consecrating the Third Coalition. Between Russia, Austria and

Sweden; Pitt projected as many as a half-million men could be put against

the French by Christmas, even more if Prussia could be lured to the allied

cause. For their part, Britain was bankrolling the operation, offering the

allies £1.25 million per 100,000 soldiers per year.

A secret treaty was signed in St. Petersburg on April 11, 1805,

officially consecrating the Third Coalition. Between Russia, Austria and

Sweden; Pitt projected as many as a half-million men could be put against

the French by Christmas, even more if Prussia could be lured to the allied

cause. For their part, Britain was bankrolling the operation, offering the

allies £1.25 million per 100,000 soldiers per year. The Austrian military was divided into three armies

under the nominal commands of Archdukes Ferdinand, John, and Charles.

Ferdinand's army, 72,000 strong, occupied parts of Bavaria (to the Iller

River), and hoped to compel the German nation to join the Coalition.

Charles was to attack Massena's Army of Italy with 94,000 troops, sweeping

through northern Italy. John, with 22,000 troops, would maintain a

defensive posture in the Tyrol until Charles had destroyed Massena, and

then provide flanking support as Charles moved through Switzerland into

France. By the time Charles was sweeping through the Alps, the Russian

army was to have combined with Ferdinand and been prepared to deal a

crushing blow to La Grande Armee, speculated to be no bigger than 70,000

troops. Two diversionary attacks were counted on; an English army was to

land in Naples and advance, along with the Neapolitan army, against

Massena. Meanwhile, a Anglo-Russian-Swedish army was to land in Hanover,

advance on Holland and encourage Prussia to declare for the Coalition.

The Austrian military was divided into three armies

under the nominal commands of Archdukes Ferdinand, John, and Charles.

Ferdinand's army, 72,000 strong, occupied parts of Bavaria (to the Iller

River), and hoped to compel the German nation to join the Coalition.

Charles was to attack Massena's Army of Italy with 94,000 troops, sweeping

through northern Italy. John, with 22,000 troops, would maintain a

defensive posture in the Tyrol until Charles had destroyed Massena, and

then provide flanking support as Charles moved through Switzerland into

France. By the time Charles was sweeping through the Alps, the Russian

army was to have combined with Ferdinand and been prepared to deal a

crushing blow to La Grande Armee, speculated to be no bigger than 70,000

troops. Two diversionary attacks were counted on; an English army was to

land in Naples and advance, along with the Neapolitan army, against

Massena. Meanwhile, a Anglo-Russian-Swedish army was to land in Hanover,

advance on Holland and encourage Prussia to declare for the Coalition.

Upon hearing of Mack's capitulation at Ulm, Kutusov

ordered an immediate retreat back across the Inn. Now commanding some

58,000 troops (including 22,000 Austrians), his goal was to link up with

Buxöwden prior to engaging the French. Napoleon, meanwhile, ordered a

pursuit, hoping to prevent this linkup from occurring.

Upon hearing of Mack's capitulation at Ulm, Kutusov

ordered an immediate retreat back across the Inn. Now commanding some

58,000 troops (including 22,000 Austrians), his goal was to link up with

Buxöwden prior to engaging the French. Napoleon, meanwhile, ordered a

pursuit, hoping to prevent this linkup from occurring.