Try Amazon Fresh

Miniature Wargames No. 24 May 1985

Having discussed the theory of skirmishing in the previous part of this essay, it now remains to examine an actual skirmish action and compare the theory with practice. Detailed descriptions of Napoleonic skirmish actions are few and far between and that describing the activities of the small corps of Prussians on the retreat after Jena and Auerstadt in 1806 in Droysen's biography of Yorck is particularly useful.

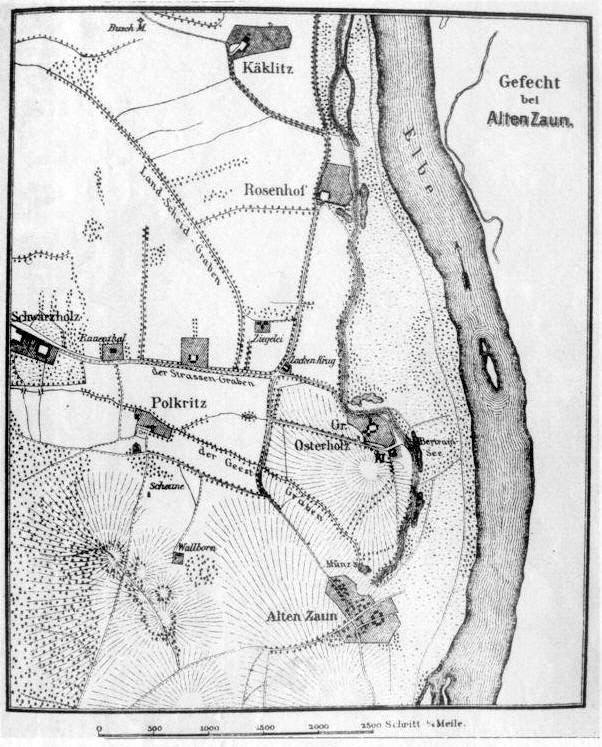

The Battle of Altenzaun was a rearguard action fought by a corps of Prussians on their retreat to the Baltic coast. Its rearguard was under the orders of the then Colonel von Yorck of the Rifle Regiment, later commander of the Prussian Auxilliary Corps in Russia in 1812 and the victor of Wartenburg and Moeckern in 1813. The force available to Yorck consisted of three battalions of fusiliers (light infantry), six companies of Jaeger (rifles) and two cannon. The terrain (see map) consisted of undulating countryside around Altenzaun itself and a plain a few hundred paces away which was scored with tree-lined roads. On one edge of the hills was a water-filled ditch known as the 'Geest-Graben' which flowed from the 'Muenz-See' pond. The plain ended at the Elbe Embankment ('Elbdamm'). On the other side of this feature were meadows. The 'Strassen-Graben' was a sunken road. It is apparent that there was a good deal of cover in which Yorck could post snipers and hide his reserve. He used the church at Polkritz to cover his right flank, placing two companies of riflemen there and in the nearby farm. They linked up with the rifle-armed 'Schuetzen' of the three fusilier battalions that were positioned behind the 'Geest-Graben'. The third rifle company covered the bushy countryside between the pond and the Osterholz, throwing out its skirmish elements to the fore. The fourth company of rifles occupied Osterholz itself, deploying its skirmishers right up to the edge of the village and over the Elbe Embankment. Zacken-Krug was the central point of the defence, being situated to the centre rear of the front line. A battalion of fusiliers was held in reserve behind it. To their front, half way to the bridge over the 'Geest-Graben', the other two battalions of fusiliers were deployed. Two companies of rifles were positioned by the sunken road. The main body had been positioned in such a way that it could be moved to any point of the front the French might attack without much delay. The French had two possible lines of advance open to them. Either they could advance along the road or along the Elbe Embankment.

Map of the battle of Altenzaun, 26th October 1806.

Yorck's deployment was a classic text-book use of light troops. The skirmish line to the fore with closed supports to the rear, behind cover but close enough to provide support rapidly. In the village, men were deployed around its edge and the reserve held centrally. Yorck had both the initiative and the element of surprise on his side.

At about 4pm, French cavalry scouts from Maragon's Division approached, moving through Alten Zaun up to the church at Polkritz. Here, fire from the rifles made them take to their heels. An hour later, infantry columns from the 26th Light Regiment advanced along the Embankment whilst their skirmishers engaged the rifles deployed between the pond and Osterholz. The strength of the French indicated that they were making a serious attempt to outflank the Prussians. Yorck moved his two companies of rifles held in reserve to re-inforce the fire line. Another was moved from the church to the left flank of the French which put the latter into a difficult situation. The Prussians were not only in a better, protected position, but they could also fire on the French from three sides with a total of 400 rifles. To cause the French even greater discomfort, Yorck then brought up his two cannon, placing one on the Geest bridge and the other on the Embankment at Osterholz and used them to bombard the French columns. Yorck judged the moment opportune to launch a counter-attack. This threw a dismounted dragoon regiment into disorder and drove the French infantry back to Alten Zaun. The Prussians lost a mere twenty casualties in this action and the French lost about six times that number. In fact, they had got such a bloody nose that they did not venture forward again until the Prussians had completed their withdrawal over the Elbe.

Yorck's tactics are worthy of closer scrutiny. Firstly, he covered his entire front with a thin skirmish line, anchoring his exposed flank on a village. This well hid his own position from the French and provided a trip-wire which he could use to ascertain their intentions. That is the correct way in which to use a skirmish line. Then he placed his reserves centrally and in such a way that they could be moved to the threatened part of the front quickly. His reserves were hidden from the enemy's view and would appear at the chosen point unexpectedly. The skirmishers themselves were deployed in advantageous positions from which they could not easily be dislodged by the enemy. They could bring their superior firepower to bear on the enemy and could launch a counter-attack to decide the issue. This battle is a clear example of Yorck's tactical brilliance and demonstrates that even in 1806, the Prussian light branch was a formidable weapon when in the right hands.

The retreat continued. In his biography of Yorck, Droysen describes a further action which gives a much clearer indication of the nature of small scale actions. The following is a selection of quotes from this work, translated by the author of this article:

"Arriving at a bridge in front of the village of Jabel, the enemy was seen in the distance, following up in strength, judging by the type of swarms of skirmishers. A manoeuvre was undertaken that had been practised often enough on the parade-ground at Mittenwald. In a broad firing line, pairs of skirmishers next to each other, one waiting for the other to load, falling back slowly until the next troop met those falling back and broke up into the firing line, in this fashion, the riflemen withdrew, their flank protected by the Brandenburg Hussars, behind the village where the battalions of fusiliers were deployed, waiting for them. This movement was executed safely and with ease and was a complete success."

It is worth analysing this deployment. The front line consists of the characteristic pairs of skirmishers. Conducting an orderly withdraw-al, the firing line first falls back on its supports and then onto the main body. All this is the sort of manoeuvre discussed in the various regulations examined in the first part of this essay.

To return to Droysen's account:

"Close to the other side of Jabel is the Nossentin Heath, a marshy, wooded area between a number of lakes. Here, the rifles were in their element, the fusiliers were pulled back and the rifles again fixed their sights on the enemy. The contrasts of high trees with undergrowth, thicket and plantations, open spaces and wooded areas were used with skill by the indefatigable Yorck, the men were hidden and allowed to take aim without being disturbed, their supports were positioned in such a way that whilst falling back slowly, they could hold up the enemy with accurate fire. The enemy was appreciably delayed.

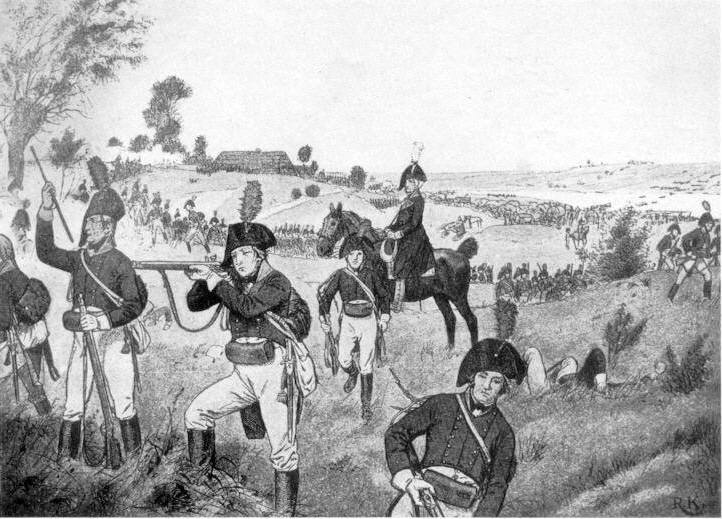

Yorck and his riflemen at Altenzaun (Knoetel). Note the pairs of men in the firing line alternately loading and firing. The close-order supports are hidden behind the ridge and out of sight and line of fire of the enemy, yet close enough to offer rapid support. The whole skirmish fight is taking place under the close supervision of the skirmish officer who is in such a position that he can observe the firing line and control the feeding-in of the reserves.

"It was thus much easier to move through the cutting just reached to the wood which began again on the other side of it. Here, the entire line of riflemen could take up an extremely advantageous position. The enemy had desisted from their pursuit and there was an hour to spare, so everybody was able to find good positions, behind the high tree trunks, in the glades, in the dense undergrowth, everywhere these marksmen were hidden and waiting, looking into the distance for the enemy, finger on the trigger, just as if they were on the hunt. At last the enemy appeared, deployed his skirmishers and advanced cockily over the open area. The rifles, however, lay still and let them come nearer and nearer until they were at the range that the good marksmen does not miss the stag; then, and only then did the rifles crack. Only a few bullets did not hit their target. The French had not expected such a greeting; those that did not fall rushed away as fast as their feet could carry them. One or two of the riflemen broke cover in pursuit. Yorck's strict order brought them back; he wanted to wait for a second advance against such an advantageous position.

"Half an hour later, a second chain of tirailleurs moved up; the rifles could not now expect to remain hidden until close range, so they commenced firing as soon as the enemy got within range of their weapons. Of course, the enemy returned fire, but against men in cover, they usually missed, whereas our carefully aimed rifle shots usually found their target.

"The enemy could make no progress with skirmishers. He had to advance in column and end this unequal battle in the woods with the final resort - the bayonet. The riflemen had reloaded. 'Messieurs, now wait!' Yorck called to them. The enemy came with bayonets flashing; he was allowed to get to thirty paces. Then the rifles cracked, every bullet struck home. That caused confusion, a sudden faltering in the charge. That had been anticipated. There was no time to reload, straight after the volley. Yorck had the signal to retreat blown and they ran back four hundred paces to where the supports were waiting.

"It was a quarter of an hour before the enemy followed. Similar scenes began again, but the enemy did not dare launch another bayonet attack. The rifles were able to fall back slowly, keeping up the fight by carefully firing at the enemy in their normal fashion. Being used to living in forests and to using the smallest advantage of terrain, they had the upper hand. It was a huntsman's joy to get the enemy in one's sights in this hunting ground covered in under-growth. The rifles crept from bush to bush, often only twenty or thirty paces from the enemy, taking aim with their accurate rifles at the boldest or the officers with terrible effectiveness, with more and more enthusiasm...."

There are a number of points of interest here in Yorck's tactics. Note how skirmishers could also use the volley to dramatic effect. The effective use of cover and the careful selection of targets are also worthy of note. Also, the best counter-measure against skirmishers was not always the use of one's own skirmishers, and close-order troops were so often needed to support the skirmish fight. Finally, officer control was essential to stop the action getting out of hand and degenerating into a scrappy encounter with no result.

The next article in this series will be looking at possible mechanisms for Napoleonic skirmishing.

Select Bibliography

Johannes Kunisch: Der kleine Krieg (Wiesbaden 1973).

Walter Wagner: Von Austerlitz bis Koeniggraetz (Osnabrueck 1978).

Johann Gustav Droysen: Das Leben des Feldmarschalls Grafen Yorck von Wartenburg (Leipzig 1913).

Herbert Schwarz: Gefechtsformen der Infanterie in Europa durch 800 Jahre (Munich 1977).

Exercir-Reglement fuer die kaiserlich-koeniglich Infanterie (Vienna 1807).

Exerzir-Reglement fuer die Infanterie der koeniglich preussischen Armee (Berlin 1812).

Part 1 - Infantry Skirmishing In The Napoleonic Wars by Peter Hofschr÷er